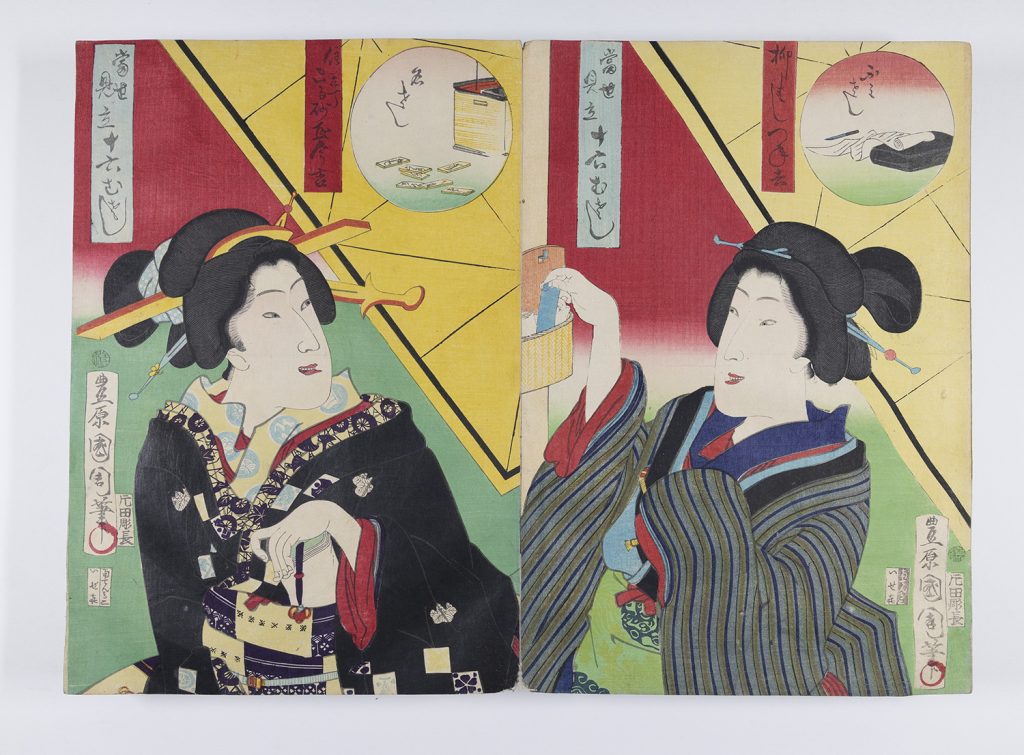

Plates 101-105: Likening nowadays to jūroku musashi

Plates 101-105: Likening nowadays to jūroku musashi

Toyohara Kunichika 豊原 国周 (1835 – 1900)

Likening nowadays to jūroku musashi (Tōsei mitate jūroku musashi 当世見立十六むさし) (1871)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki (Manyōdō)

Censor: unknown

Carver: Katada Hori Chō

Artist: Toyohara Kunichika hitu with toshidama seal

These 5 prints are from what was likely a larger 16-print series by artist Toyohara Kunichika (1835 – 1900). At first glance, the prints look to be examples of bijin-ga 美人画(prints of beautiful women). Bijin-ga prints were especially popular during the Meiji period (1868 – 1912), and Kunichika was also a prominent artist of bijin-ga prints.1

But further examination reveals these prints are much more than traditional bijin-ga prints. In fact, they are not even a Kunichika “original.” The prints appear to be a copy of the series Parody of the sixteen musashi (mitate juroku musashi) by Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865), under whom Kunichika trained as an apprentice artist of the Utagawa school.2 Kunichika’s career in many ways followed Kunisada’s, both in time and in style. Kunichika and his peers from the Utagawa school attempted to continue the legacy of their predecessors.3 Kunichika particularly attempted to paint himself as a “direct heir” of Kunisada. For example, Kuinsada often incorporated Kunisada’s red toshidama cartouche or seal in his signature, which is visible in the author’s seal of these prints.4 In that context, the copied nature of these prints becomes particularly interesting evidence of Kunichika’s campaign to emulate Kunisada in his artwork.

The series that Kunichika copies here is also unique in that the series is based on a popular board game of the time, juroku musashi 十六むさし. Juroku musashi is a traditional Japanese military strategy game with 16 pieces, each representing soldiers and generals. It is likely that the complete series would have contained 16 prints, each representative of a game piece. Traditionally, pieces in juroku musashi would contain images of military men, such as in this board by Hitasaro Suzuki.5 Kunichika’s (and originally Kunisada’s) work, however, inverts gender roles, placing beautiful women as the “soldiers” and “generals” of the game.

This work’s title indicates that the series is an instance of mitate-e 見立絵, a subgenre of ukiyo-e that uses allusions and juxtaposition for the purpose of parody. Specifically, mitate-e puts two objects together, using one object to stand in for another and revealing a figurative or symbolic reality superimposed on the original object.6 In this case, the juxtaposition of the beautiful women (bijin-ga) against the traditionally militaristic board game (juroku musashi) was likely an attempt to leverage mitate-e to parody the contradictions in Japanese culture at the time. Specifically, the print plays on the contradiction between a graceful or beautified appearance and violent undercurrents. Because of harsh restrictions from the government, mitate-e and other forms of parody were often used to critique current events without being censored, especially given the harsh government restrictions on entertainment and art of the preceding Edo period (1603 – 1868).7 Because of the required subtlety, it is difficult to fully identify today what this work attempts to parody specifically. Some examples of potential interpretations could be a parody of a particular military campaign, a parody of traditional home-making customs, a parody of gender roles, or a parody of board games themselves.

These prints provide an interesting example of the dynamic between ukiyo-e artists and their successors, as well as the creativity of utilizing mitate-e to craft thought-provoking artwork out of popular, but relatively commonplace objects.

Samantha McLoughlin

Economics and Computer Science

Class of 2025

Annotated Bibliography

Mueller, Laura Jean. “Competition and Collaboration in Edo Print Culture: Lineage, Creative Specialization and Market Eminence for Artists of the Utagawa School, 1770 – 1900.” Madison ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2015. http://proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/dissertations-theses/competition-collaboration-edo-print-culture/docview/1751011263/se-2.

This article analyzes the relationships between artists from the Utagawa school, including Kunichika. Specifically, it describes Kunichika’s attempts (and perhaps, failures) to continue the school’s legacy, as well as his interpersonal relationships with other artists.

Nishiyama, Matsunosuke, and Gerald Groemer. Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600-1868. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 1997.

This book has a section describing how mitate was used to subvert strict censorship laws in Edo period Japan.

Shirasu, Yoko. “Mitate and Metaphor in Multicultural Japan.” Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences 2, no. 3 (September 30, 2020): 45–52.

This article describes the use of mitate for the purpose of using art and media for social commentary. Specifically, it compares how the Japanese conception of mitate differs from and goes beyond the concept of a metaphor.

Stephens, Amy Reigle, and Shigeru Oikawa. Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master Toyohara Kunichika, 1835-1900. Leiden [Pays Bas]: Hotei Publ, 1999.

This book includes a variety of Kunichika’s prints, both actor prints and bijin-ga prints, as well as a documentation of his early life, training, and legacy. Specifically, there is a section on the evolution of Kunichika’s bijin-ga prints in relation to cultural beauty standards, as well as the change in his representation of women from stiff to lively.

Suzuki, Hisataro. 吉例壽曾我十六むさし. 1909. Pictorial works. https://catalog.princeton.edu/catalog/9951808123506421#view.

This is an example of a juroku musashi board game.

Van Assche, Annie. “Changing Perceptions of Ideal Beauty in Early Twentieth Century Japan: Kyoto School Bijin-Ga.” University of Hawai’i at Manoa ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996. http://proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/changing-perceptions-ideal-beauty-early-twentieth/docview/2486552540/se-2.

This article describes the evolution of the standard of “ideal beauty” in the context of bijin-ga. Specifically, it has a section detailing the critical role ukiyo-e prints played in the emergence and development of bijin-ga, and how these works can often be seen as a reflection of societal standards.