Plate 140-149: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Prints

Plate 140-149: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Prints

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 月岡芳年 (1839-1892)

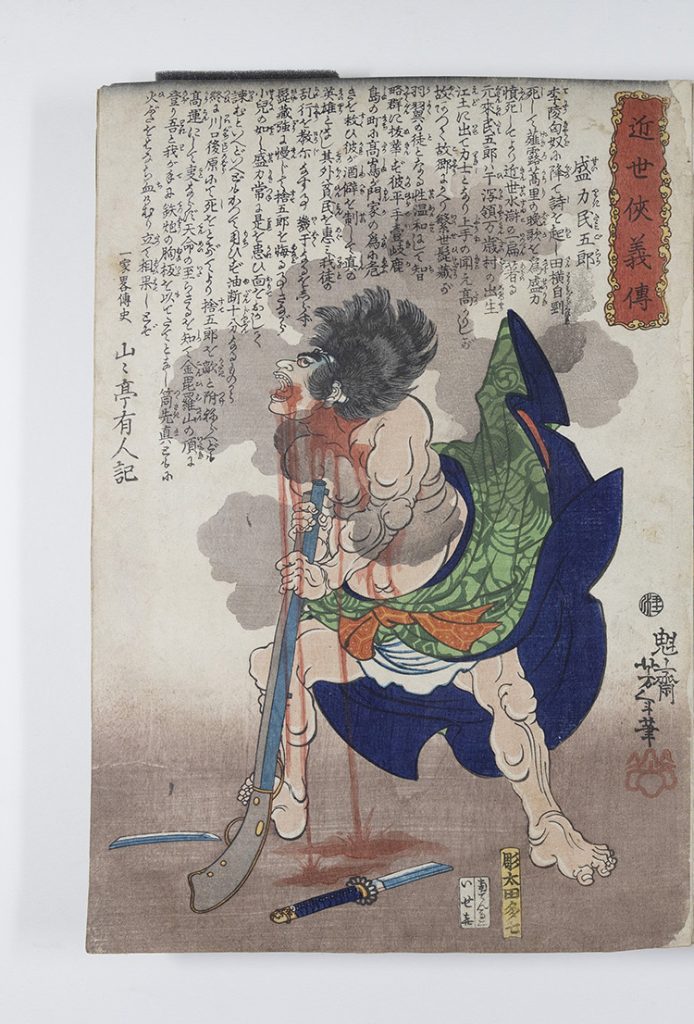

Seri Tamigoro Committing Suicide (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/11

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Mizushima Umon holding a pistol while standing by bundle of spears (1866)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1866/4

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

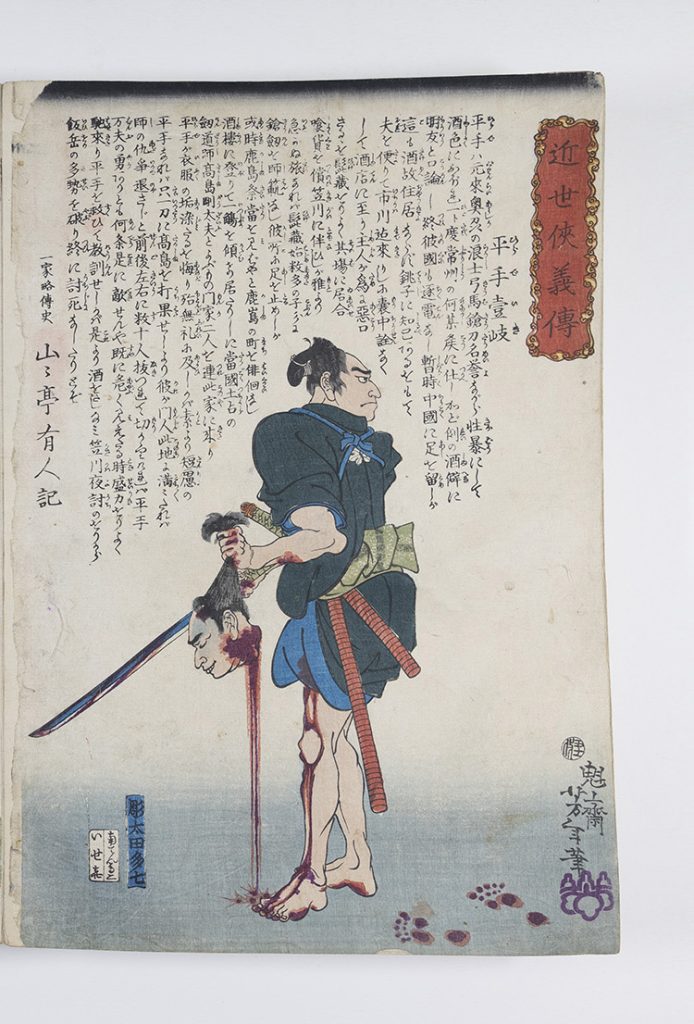

Hirade Iki with a severed head (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/11

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

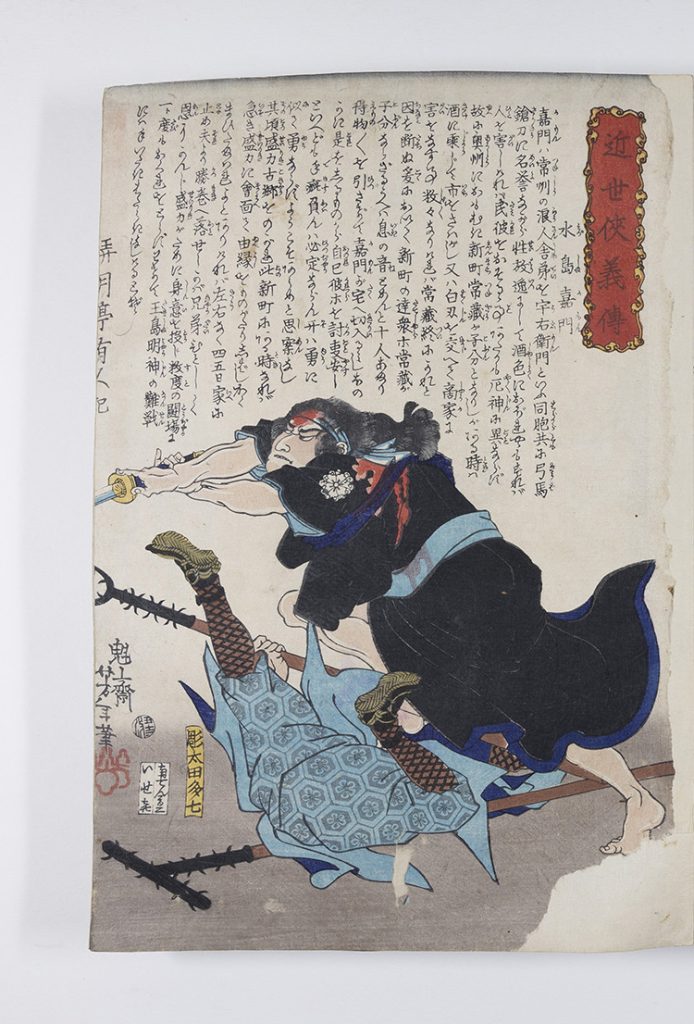

Mizushima Kamon slashing at an assailant with a pike (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/12

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Iiokano Sutegorō pinning assailant with a broken pot (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/11

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

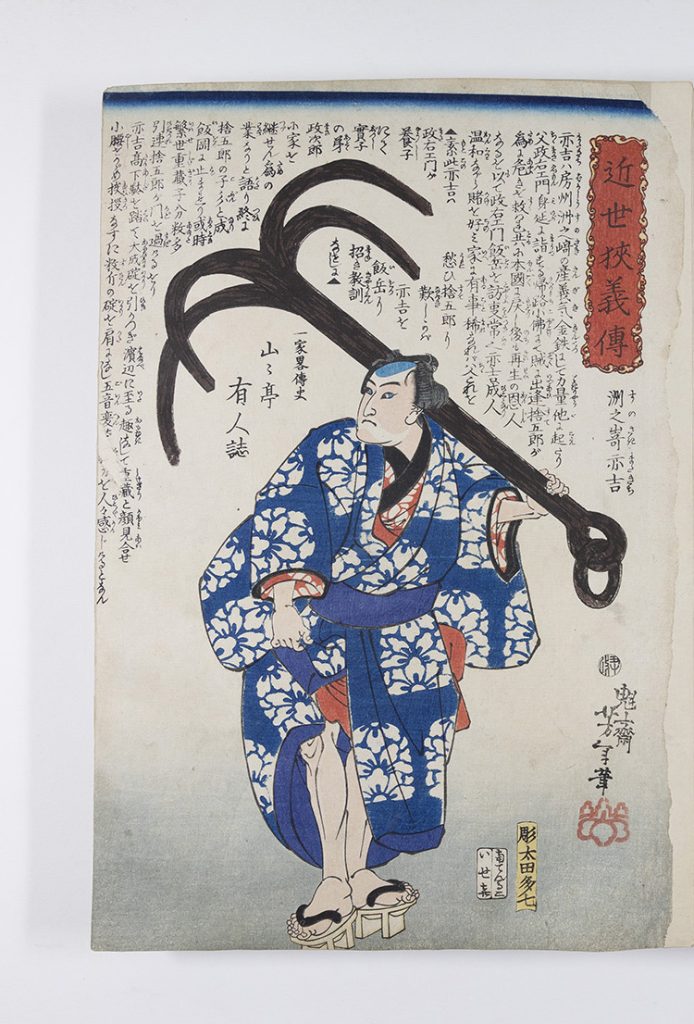

Sunosaki Matakichi holding an anchor (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/10

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

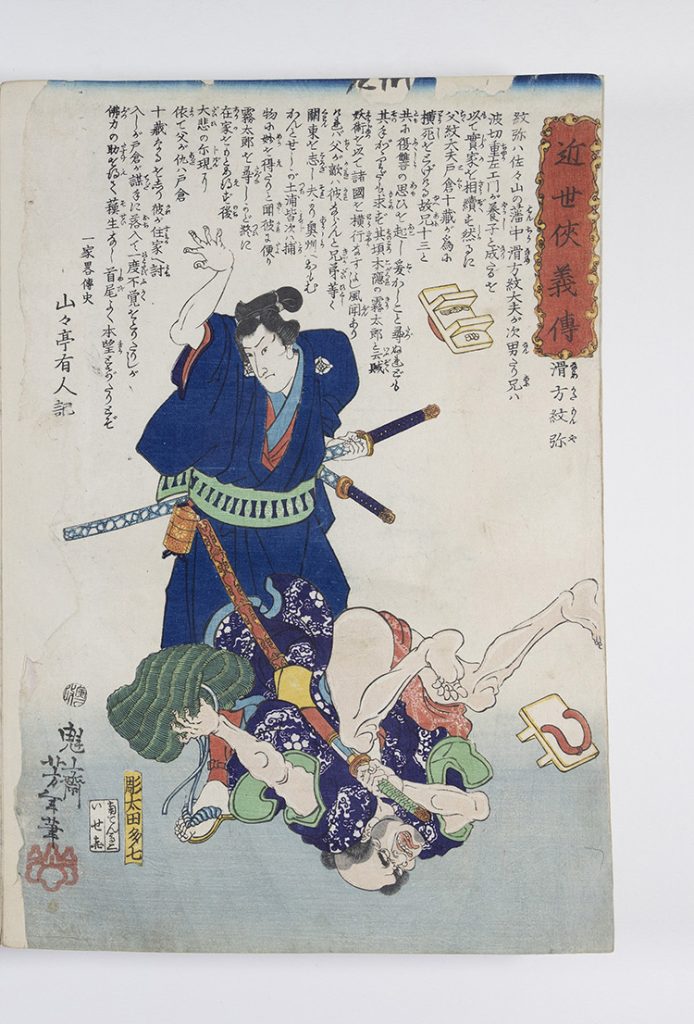

Namekata Monya throwing an assailant to the ground (1866)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1866/2

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

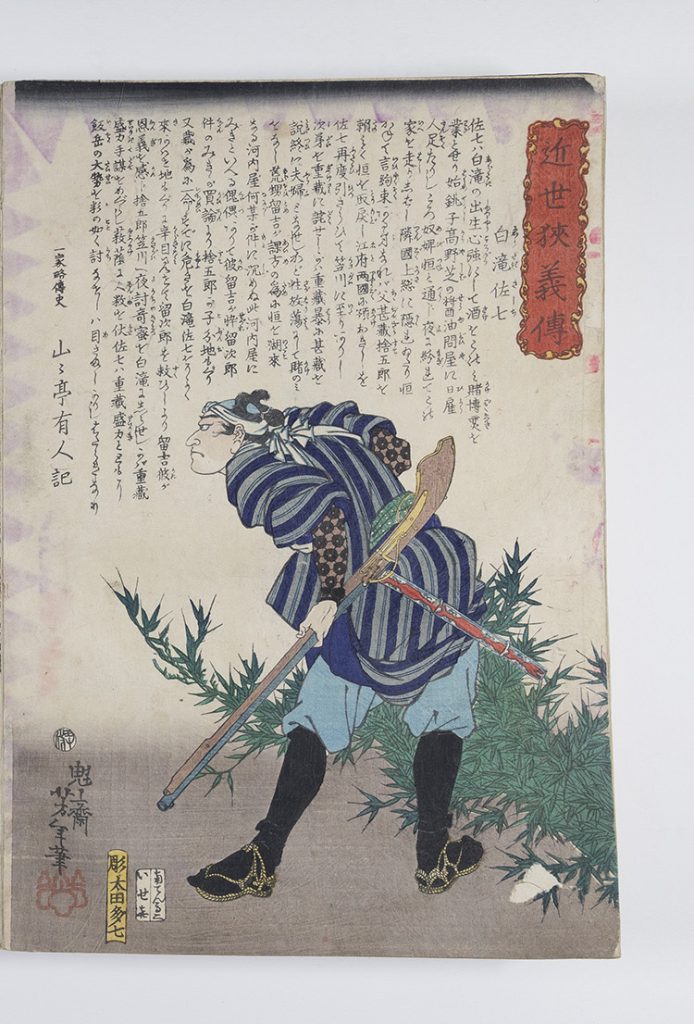

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Shirataki Sashichi holding a rifle (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/10

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

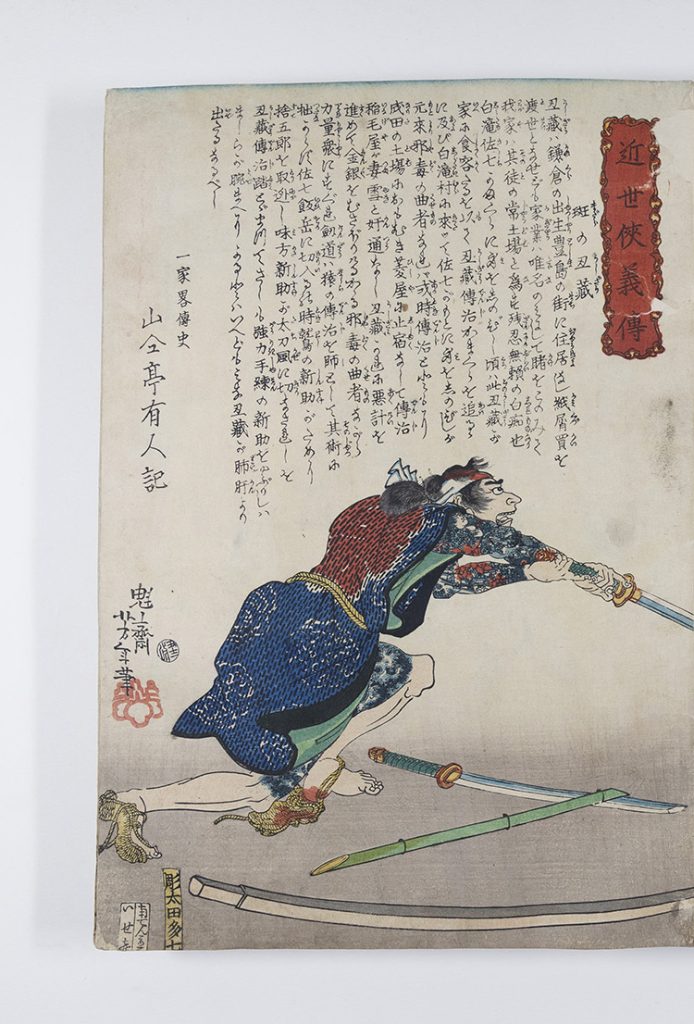

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Madara no Ushizō lunging with a sword (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/12

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

Natsume Shinsuke with blood dripping from a sword (1865)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Iseki

Censor: 1865/12

Carver: unknown

Artist: Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi)

Mid-nineteenth century Japan, even before the Meiji Restoration of 1868, was in the midst of a rising level of domestic political unrest and antagonism from foreigners. The depiction of Suikoden 水滸伝, the Japanese translation of the thirteenth-century Chinese work Tales of the Water Margin (shuǐ hǔ zhuàn 水浒传) became a popular underlying theme of many prints during this period.1 The legend of 108 outlaw heroes who fight in the face of an unjust and corrupt government became an inspiration for the Japanese artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892).

In the April of 1839, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, a Japanese woodblock prints master, was born in the city of Edo to a merchant.2 Wanting to gain social status, Yoshitoshi’s father purchased a position in the samurai family, Yoshioka Hyōbu 吉岡兵部.3 With high status does not always come a happy childhood. Yoshitoshi’s parents divorced early on, and he eventually left his father to live with his uncle possibly because of the complicated situation in his household.4

Aside from his personal life, Yoshitoshi eventually studied under Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1798-1861), a third-generation master of the Utagawa school.5 Departing from the traditional actor and beauty themes, Kuniyoshi had earned a special position in the Utagawa school by establishing a new subject in ukiyo-e, warrior prints.6 This new subject of prints became popular during the Meji Restoration (1868-1889), when society shifted from a period of political calm to turmoil and military exploits.7 The preference in painting warriors also affected his student Yoshitoshi who produced a large number of warrior prints.8 Upon joining the studio, Yoshitoshi quickly became one of Kuniyoshi’s favorite students due to his enthusiasm and talent.9 However, jealousy arose, and Yoshitoshi was bullied by fellow student Yoshiiku 芳幾 (1833-1904) during his late adolescent years which could have contributed to the violent and bloody depictions in his work during the mid-1860s.[cm_simple_footnote id=10] Both his experience in the studio and complicated personal background informed the stylistic elements and bloody portrayal of characters in his artworks.

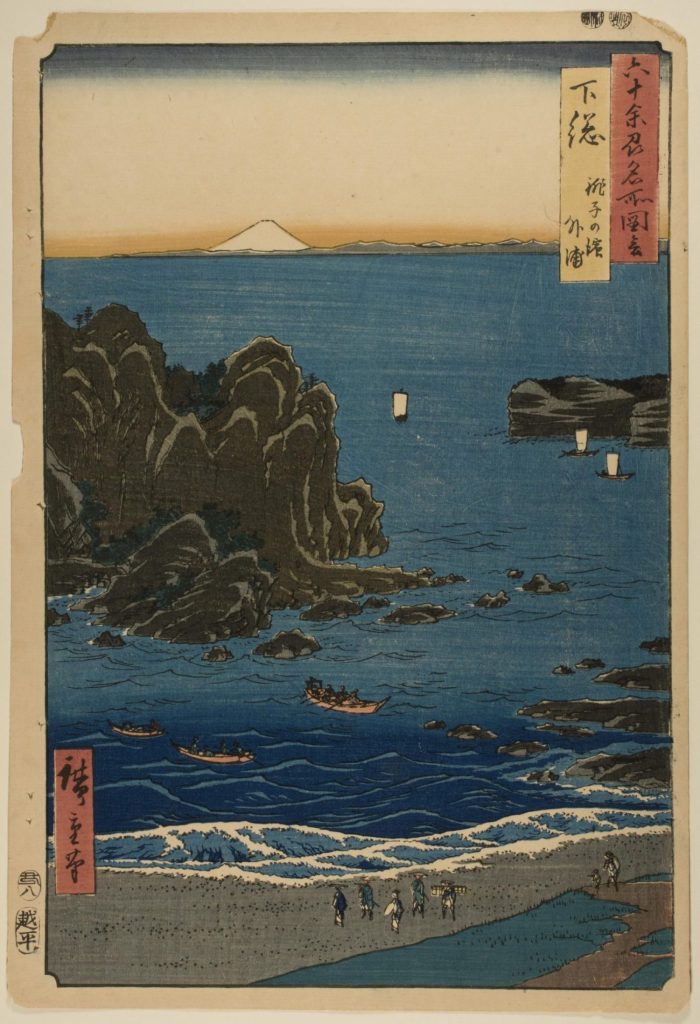

The series Biographies of Modern Men (Kinsei kyogiden 近世侠義傳) was one of his earliest attempts to depict heroic actions of non-conformists – men who often act to disrupt established order. This set of prints featured 36 gamblers from the battle between Hanzo Sasagawa and Sukegoro Iioka.11 The subjects of Biographies of Modern Men were members of two gambling gangs led by Iioka Sukegoro and Hanzo Sasagawa. The two gambling gangs had a power struggle for the port town Choshi in Shimōsa Province (Shimōsa no Kuni 下総国, present-day Chiba prefecture) because of its geo-economic supremacy (Figure 1).12 Benefitting from its huge flat riverbed bordering the Pacific Ocean, Choshi had a thriving fishing industry that was central to the local economy. In the fight to gain the spheres of influence of the area, Hanzo plotted to murder Sukegoro, but Sukegoro learned about the plan and acted first with a night raid. Although Hanzo was put at a disadvantage with only 25 supporters, they were able to drive away Sukegoro’s force suffering only one casualty.13 The fight between the gambling rings continued even after this confrontation, and the portraits in Biographies of Modern Men include both illustrations of this battle and subsequent fighting.

Although formally known as criminals, the Suikoden-like characters were popular subjects of woodblock prints at the time, because they were considered as revered heroes for their rebellion against government corruption and exploitation of poor people. This resonated with the many who struggled to survive under the authority and domination of the Tokugawa shogunate of the previous period. The criminal nature of these characters was testified by the body tattoos — for example those on Madara’s arms and thigh from the piece “Madara no Ushizō lunging with a sword”, which had a strong association with Japanese organized crime and were often worn by working class people (Figure 2).14 The display of symbolically barbaric and undesirable feature was a manifestation of Yoshitoshi’s social and political subversion.

Another work in the Pendergrass album is “Tamigoro committing suicide” which dates to the 11th month of 1865 in ōban size (10 by 15 inches), one of the most standard paper sizes during the time (Figure 3).15 In the bottom right corner, Yoshitoshi signs “Kaisai Yoshitoshi hitsu” (Brushed by the Pioneer Yoshitoshi) followed by a seal Yoshi which is Kuniyoshi’s paulownia-leaf monogram.16 This print depicts a figure committing suicide against a very plain background with long text on top and the name of the series in the top right. The man in the picture is Seiriki Tamigoro a famous wrestler who kills himself after avenging his father-in-law’s murder.17 Yoshitoshi depicts the moment when Tamigorō fires a musket into his own chest and creates a sensational impact with the blood gushing out of the wounds. Stylistically, Yoshitoshi renders the facial expressions in curved calligraphic lines and nods to realism with the outlining of the strong muscles. The broken sword laying by his feet may be the weapon that he used to carry out the vendetta against the murderer. We could attribute the inclusion of this character in a series on modern heroes to the idea of filial piety that exists in Buddhism and Confucianism, which were prominent traditions in the Edo period.

Rhea Huang

Economics and Computer Science

Class of 2024

Sunny Li

Economics and Mathematics

Class of 2023

Annotated Bibliography

Keyes, Roger. “Courage and Silence: A study of the life and color woodblock prints of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi: 1839 – 1892 (Volumes I and II).” PhD diss., The Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities, 1982.

Roger Keyes’s work consists of two volumes, one on the chronology of Yoshitoshi’s work and the other on the production of the prints. For each year starting from 1839 to 1950, Keyes provides an account of historical events, personal information, work during that year, and anecdotes, if available. The year 1865 and 1866 chronology is especially important for the study of his more bloody paintings in the Biographies of Modern Men series.

Keyes, Roger. The Bizarre Imagery of Yoshitoshi: the Herbert R. Cole Collection. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1980.

Roger Keyes discusses Yoshitoshi’s artistic style and his life story, including a detailed description and analysis of 67 prints by Yoshitoshi. The sections on warrior prints, techniques, and style explain the motivation and the stylistic rendering behind the prints between 1865-1866. The analysis of relevant prints produced during this time also sheds light on the mentality of the artist at the time.

Van den Ing, Eric and Robert Schaap. Beauty & Violence: Japanese Prints by Yoshitoshi, 1839 – 1892. Netherlands: Society for Japanese Arts, 1992.

The authors draw on a close study of the society at the time and its effect on the images that Yoshitoshi produced. In addition, the book describes Yoshitoshi’s early life and the way that his images speak to his childhood experience. While this source offers an overview of Yoshitohi’s career and life starting very early, it would be useful for the study of his prints around 1865 as early experiences may have affected on his style and choice of subject at the time.

Segi, Shinichi. Yoshitoshi: The Splendid Decadent. Translated by Alfred Birnbaum. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1985.

The book introduces in detail the Utagawa school, Yoshitoshi’s career, and his artistic techniques. It provides context for one of the prints in the Biographies of Modern Men series which is Tamigorō Commits Suicide. The book not only offers information on the series that this print belongs to but also the life story of Tamigorō.

Skutlin, John Michael. “Japan, Ink(Ed): Tattooing as Decorative Body Modification in Japan.” PhD diss., The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong), 2017.

The dissertation discusses the symbolic significance of tattoo in Japanese society, which explains the non-conformist’s nature of the samurai from Biographies of Modern Men

Turnbull, Stephen. “Swords in Society.” In Samurai Swordsman: Master of War, 117–18. TUTTLE Publishing, 2008.

The book elaborates on the battle between Hanzo and Sukegoro in the fighting for dominance of the Choshi areas.