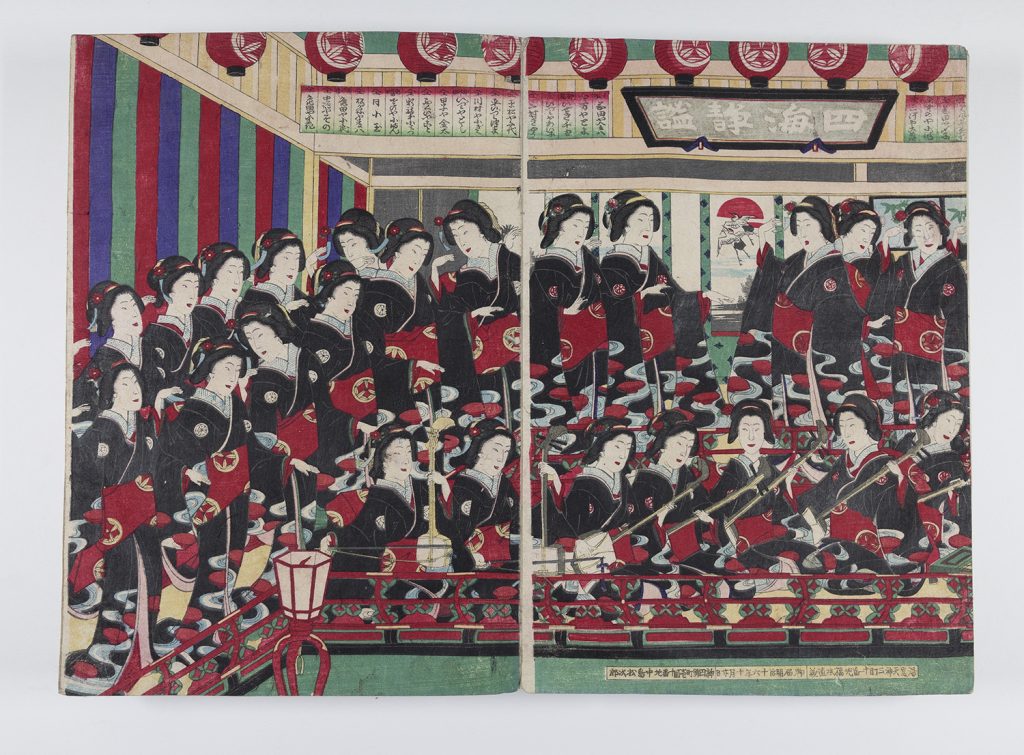

Plates 92-94: Image of the Furuichi dance at Shintomi-za

Plates 92-94: Image of the Furuichi dance at Shintomi-za

Yōshū Chikanobu 楊洲周延 (Toyohara 豊原) (1838-1912)

Image of the Furuichi dance at Shintomi-za 新富座古市踊の圖 (1883)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Unknown

Censor: None

Carver: Unknown

Artist: Yōshū Chikanobu

Toyohara Chikanobu (1838-1912), born in Edo to a samurai family, is best known for his nishiki-e (full-color woodblock prints) that became popularized in the 1880s and 1890s.1 Chikanobu specialized in depictions of bijin-ga 美人画 (beautiful women) and Meiji period (1868-1912) events, and this piece represents his typical 1880s work. However, as the Meiji period moved from traditional styles and practices, Chikanobu became known for his nostalgia for Edo-period (1603-1868) culture. Compared to his peers, Chikanobu’s art style is considered fairly conservative and somewhat resistant to foreign influence.2

The focal point of this print is the group of thirty-six women performing in the Shintomi-za Theater. Towards the bottom of the print, Chikanobu depicts women playing the traditional Japanese instruments of the shamisen 三味線, kokyū 胡弓, and koto 琴, while those above participate in dance and song.

Mastering traditional Japanese instruments, particularly the shamisen, provided social capital for women in the townsman class in the late Edo period.3 By demonstrating skill in the shamisen, women increased their chances of serving in a samurai home, which was considered to be a reputable education. However, within samurai families, playing the shamisen was not considered a respectable occupation.

Artist: Unknown, Date: 1870s, Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The song and dance performed by the courtesans in this print is known as the Furuichi dance, which is traditionally performed to the folk song Ise ondo 伊勢音頭. The dance is named after the town of Furuichi, which held one of the most prominent pleasure quarters of the eighteenth century and eventually became a center of kabuki.4 The role of women in the performing arts remained complex through the Edo and Meiji periods, as generations of musical entertainment in the pleasure quarters both glamorized and sexualized professional shamisen players and dancers.

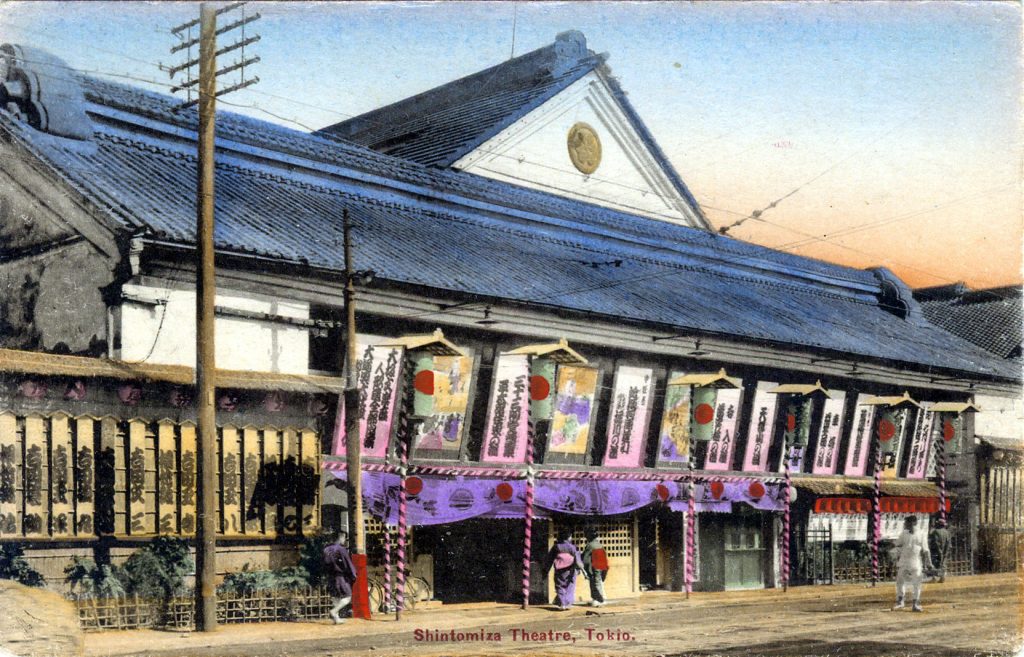

The Shintomi-za Theater, originally the Mortia-za but moved and renamed in 1872, marked a turning point of traditional kabuki in Japan. Placed well outside of the established kabuki district in Toyko, the Shintomi-za distinguished itself with Western-style architecture, chandeliers, and gas lamps (which are depicted in the lower part of the left and right Chikanobu print, outlined in red). Kabuki actors in the Shintomi-za performed in traditional western attire to western music.5 While the geisha performance shown in this print represents traditional Edo culture, this depiction contrasts with the modern Meiji-period aspects of the Shintomi-za during the time that the print was made. Chikanobu’s depiction of traditional dress and performance in the westernized Shintomi-za demonstrates his inclination toward nostalgia for Edo culture amidst the transition into Meiji culture.

Artist: Unknown, Date: 1920s, Source: oldtokyo.com

Joyce Sanks

Earth & Environmental Sciences and Biological Sciences

Class of 2024

Annotated Bibliography

Coats, Bruce Arthur, Allen Hockley, Kyoko Kurita, and Joshua S. Mostow. Chikanobu: Modernity and Nostalgia in Japanese Prints. Leiden, The Netherlands: Hotei, 2006.

This survey includes many of Chikanobu’s works, as well as a detailed history of his career.

Takahashi, Yuichiro. “Kabuki Goes Official: The 1878 Opening of the Shintomi-Za.” The Drama Review 39, no. 3 (1995): 131–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/1146469.

This article discusses the turning point in the public’s perception of kabuki that began with the opening of the Shintomi-za theater in Tokyo in 1878. The theater’s design made the atmosphere more Westernized and targeted a higher-class audience than traditional Kabuki. This print depicts a performance for the Shintomi-za theater.

Tanimura, Reiko. “Practical Frivolities: The Study of Shamisen among Girls of the Late Edo Townsman Class.” Japan Review, no. 23 (2011): 73–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41304924.

This article discusses girls’ education in the late Edo period, specifically the performing arts, as a part of a larger investigation into Early Modern period culture. Tanimura compares specific Edo-period practices to the Meiji period and to nineteenth-century England. The triptych above, made during the Meiji period, depicts several women, singing, dancing, and playing instruments, such as the shamisen–practices discussed in Tanimura’s article.

Teeuwen, Mark and Breen, John. “Pilgrims’ Pleasures.”A Social History of the Ise Shrines: Divine Capital. New York: Bloomsbury Academic (2017): 139-163 https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474272780.

This book is the first to trace the history of the Ise shrine complex from its beginning in the seventh century until the present day. The Ise complex was the most popular pilgrims’ attraction in the land from the sixteenth century onwards. This text provides context for the origin of the Furuichi dance depicted in the print.