Plates 113-114: Famous Sights of Ikaho Onsen (Hot Spring)

Plates 113-114: Famous Sights of Ikaho Onsen (Hot Spring)

Not attributed

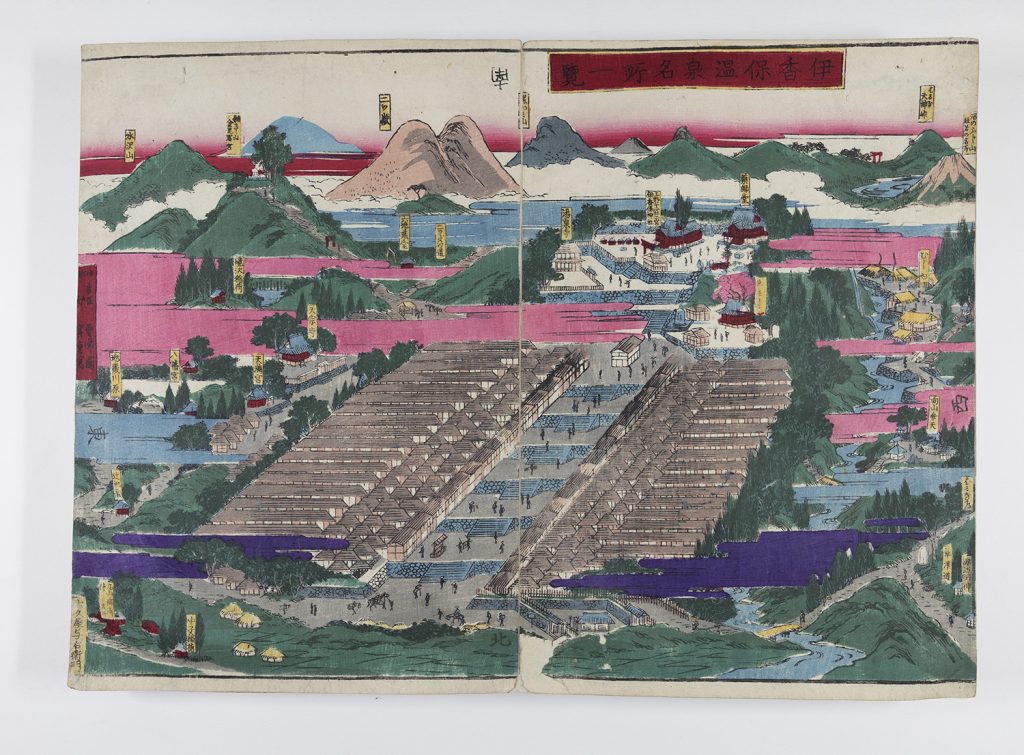

Famous Sights of Ikaho Onsen (Hot Spring) (Ikaho Onsen meisho ichiran 伊香保温泉名所一覧)

Meiji Period (1868-1912)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Unknown

Censor: Unknown

Carver: Unknown

Artist: Unknown

This ukiyo-e print depicts Ikaho Onsen, a small hot spring town located in the modern-day Gunma Prefecture of Japan. Several versions of this print have been created, and the various versions have been credited to either Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重 (1797-1858) or Seppo (unclear). The print is a hybrid of a landscape and map. Like a map, it has the four cardinal directions written on each edge, and the characters are facing outwards instead of being uniformly oriented with the bottom of the character aligned with the bottom of the image. However, instead of the overhead view common in most maps, the design is more like a landscape created from the perspective of someone looking over the town from a neighboring mountainside.

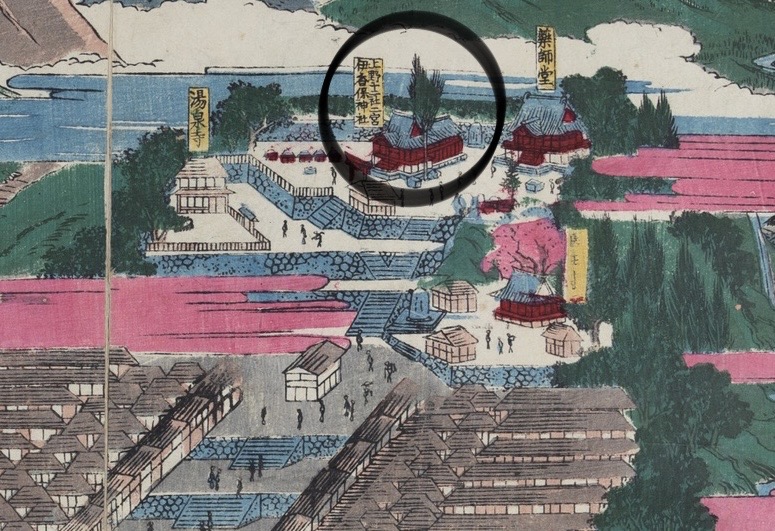

This map/landscape hybrid was likely used for tourism purposes. After stopping at the hot spring during a trip, tourists could take home this print as a memento. The prints also served a practical purpose by helping tourists find places on the map during their visit. The small, yellow labels, or cartouches, point out the major sites. One important site is the Ikaho Jinja 伊香保神社 shrine, which lies at the top of Ikaho’s iconic stone steps in the center of town. According to locals today, climbing the 365 steps to reach the shrine will bring good luck and fortune.1

Hot springs like Ikaho had multiple purposes. In addition to serving as a rest stop for travelers, hot springs served as important cultural and religious sites. It was widely believed that hot springs contained healing properties. The baths were treated like pilgrimage sites for people hoping to cure their ailments.2 Ikaho in particular was known for its kogane no yu 黄金の湯, meaning “golden (hot spring) water,” which got its brownish-gold color due to oxidized iron in the water.3 Beyond those looking to heal illnesses, Ikaho attracted a varied customer base for vacation. People from all classes would use the baths from high-ranking visitors to low-ranking locals.4 Hot spring baths were one of the few places where all classes could interact with one another, and the history of hot springs like Ikaho provide insight into multiple levels of Japanese society.

In addition to providing insight into societal practices, this print also demonstrates shifts in woodblock print production. The print contains some unique color choices, namely the vibrant purple and pink clouds. Both colors were created using synthetic dyes. This means the print was created during the Meiji period, when synthetic dyes were more widely imported from Europe. The purple color was likely created using a dye called rosaniline, which was first used in ukiyo-e prints in 1864.5 The pink dye was likely created using a chemical called eosin, which was introduced to Japan in 1877.6 This print is representative of aesthetic changes prompted by the introduction of more European products and ideas during the Meiji period. A seemingly simple image of a town, this print provides modern viewers a glimpse into Meiji period life through its purpose, subject matter, and color use.

Katherine Dodge

Human Organization and Development

Class of 2025

Annotated Bibliography

Cesaratto, Anna, Yan-Bing Luo, Henry D. Smith II, and Marco Leona. “A timeline for the introduction of synthetic dyestuffs in Japan during the late Edo and Meiji periods.” Heritage Science 6, no. 22 (April, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-018-0187-0.

This article analyzes the colors used in nishiki-e prints in the 1800s through Raman spectroscopy. It provides information on the chemicals used to create synthetic colors and provides a timeline for when certain dyes were imported to Japan.

Gunma Prefectural Government. “Oyado Tamaki.” Visit Gunma. Last modified February 17, 2021. https://www.visit-gunma.jp/en/spots/oyado-tamaki/.

This government-run tourism website for Gunma explains many popular sites within the prefecture. This section describes Oyado Tamaki, a traditional-style inn that utilizes Ikaho’s famous hot springs. It also briefly describes the type of water in the hot springs. It is important to note that this website is government-run, and the author and their training is unknown.

Gunma Prefectural Government. “Ikaho-jinja Shrine.” Visit Gunma. Last modified December 21, 2020. https://www.visit-gunma.jp/en/spots/ikaho-jinja-shrine/.

This government-run tourism site provides information on famous sites with Ikaho Onsen. This section describes the Ikaho-jinja shrine, which is featured in the print. As mentioned above, this website is government-run, and the author and their training is unknown.

Nenzi, Laura. “Chapter 7. Bodies, Brothels, and Baths: Travel and Physical Re-creation” In Excursions in Identity: Travel and the Intersection of Place, Gender, and Status in Edo Japan, 165-185. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

This book analyzes the ways early modern travelers interacted with places of tourism in Japan during the Edo period. This chapter focuses on the role of baths in Japanese society.

Tarui, Yuki. “The Modernization of Ikaho Onsen from the Viewpoint of Changes in Written Medical Onsen Benefits: The Onsen Ranking Chart, Colored Woodblock Prints, and the Guidebook to IKAHO Onsen.” Tourism Studies Review 2, no. 2 (2014): 155–68. https://doi.org/10.32170/tourismstudies.2.2_155.

This article discusses Ikaho’s physical and functional transformation during the Meiji period through studying woodblock prints and other historical documents. The article specifically focuses on the medical benefits of the onsen.