Plates 04-05: Play Prints

Plates 04-05: Play Prints

Artist Unknown

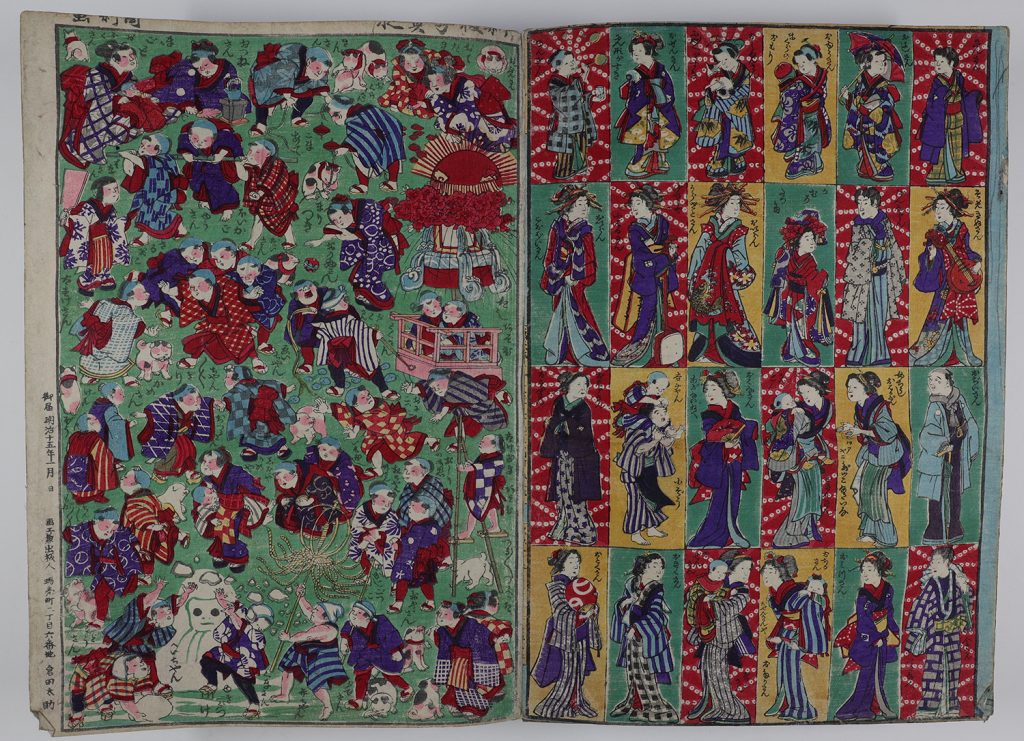

Play Print with Children with Toys and Cats

(1st Month of 1882)

Ink and color on paper

Publisher: Kurata Tasuke 倉田太助

Artist Unknown

Play Print with Women, Children, and Men

(9th Month of 1883)

Ink and color on paper

Publisher: Matsuno Sadashichi 松野定七

While modern viewers often look at ukiyo-e prints as pristine works of fine art, many were actually objects of public consumption meant to be interacted with physically as well as visually. One of the best examples of how prints invite this form of engagement is the existence of “play prints,” also known as asobi-e 遊び絵 (play picture) or omocha-e おもちゃ絵 (toy print).1 These prints were designed to be cut up and folded for children’s enjoyment and education, so few are left in good condition.2 Play prints were prolific and affordable, meaning that they were incredibly accessible to the average urban child.3 However, both children and adults could enjoy these prints.4 Play prints are an understudied area of ukiyo-e, especially in English-language scholarship, that is generally overlooked because of its association with children. However, they are no less important to the greater narrative of ukiyo-e than prints made for adults. While many artists remained anonymous, one artist, Utagawa Yoshifuji 歌川芳藤 (1828-1887), became known for his play prints.5 While these two prints are not signed, it is possible that Yoshifuji contributed to one or both of the works.

Plate 4 (right) is a type of omocha-e that was meant to be cut along the lines and either folded into a book or pasted onto blocks. Because this print was theoretically made to played with and thus possibly destroyed in play, the colors do not line up perfectly with the outlines, a sign of the inexpensive nature of these prints. However, the bright colors distract from imperfections.6 The Pendergrass Compilation Album has two versions of this print, the other of which has brighter colors and finer details. Likely, these two prints were made from the same blocks, but this one is a later edition made with less care and also left out in the light more—as indicated by the faded colors.

Plate 5 (left) is a specific type of asobi-e called monozukushi 物尽し. These prints exhibit a collection of similar or related objects. During the Meiji period (1868-1912), production of play prints increased because of an increased value in childhood education.7 These prints are visual ways to communicate information and sometimes include explanatory text.8 Children could look at them and learn the names and appearances of different objects. In this particular print, children are playing alongside cats with a variety of toys. Some of the names of these toys are included as well as some “names” of children. Children are seen in many play prints, and cats are a common motif in ukiyo-e prints more generally.9 This print could have been used by children with adults to learn new vocabulary. People of all ages would have been able to enjoy this print as a tool for learning and engagement as well as an interesting work of art.

Hana Wooley

Art History & Educational Studies

Class of 2024

Annotated Bibliography

McGowan, Tara. “Before Pokémon and Yo-kai Watch: A Window onto One of the Earliest Unique Forms of Japanese Animé at the Cotsen Children’s Library.” Cotsen Children’s Library (blog). February 2, 2018. https://blogs.princeton.edu/cotsen/2018/02/omocha-e/.

This text presents the toy print genre of ukiyo-e as generally overlooked and seen as frivolous by Westerners. It outlines that the prints were designed to be actively engaged with through play, cutting them up and re-assembling them, so very few are found in pristine condition.

McKee, Dan. “What Are Asobi-e?” Artelino. Last modified December 2, 2018. https://www.artelino.com/articles/asobi-e.asp#:~:text=Asobi%2De%2C%20or%20%22play,in%20Western%20languages%20to%20date.

Artelino is an auction house that specializes in Japanese prints and created this article entry about asobi-e (play picture) as are woodblock prints that are used mostly by children for education and play. The majority of these prints were made in the 19th century. Asobi-e exemplify how ukiyo-e prints were seen as objects of public consumption and entertainment.

Salter, Rebecca. Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006.

One of the few English-language sources on play prints, this book is by an artist who has spent considerable time in Japan and studying woodblock prints. Salter explains play prints as exemplifying the purpose of ukiyo-e prints: to be enjoyed as a part of everyday life. She argues that asobi-e were generally designed for adults who had more cultural knowledge while omocha-e were straightforward and for kids. Most asobi-e were zukushi that covered a wide range of subjects.

Tezuka, Miwako. Life of Cats: Selections from the Hiraki Ukiyo-e Collection. New York: Japan Society, 2015.

Tezuka discusses cats as a popular motif in these prints and were a part of everyday life in Edo and Meiji Japan. The book also identifies that, in addition to play, omocha-e prints conveyed moral lessons based in Confucianism. These prints were countless and everywhere, often with anonymous artists because of the cheap mass production.