Plates 11-12: A scene from the play Banzui Chōbei’s Vegetarian Chopping Block

Plates 11-12: A scene from the play Banzui Chōbei’s Vegetarian Chopping Block

Utagawa Kunihisa II 二代目 歌川国久 (1832-1891)

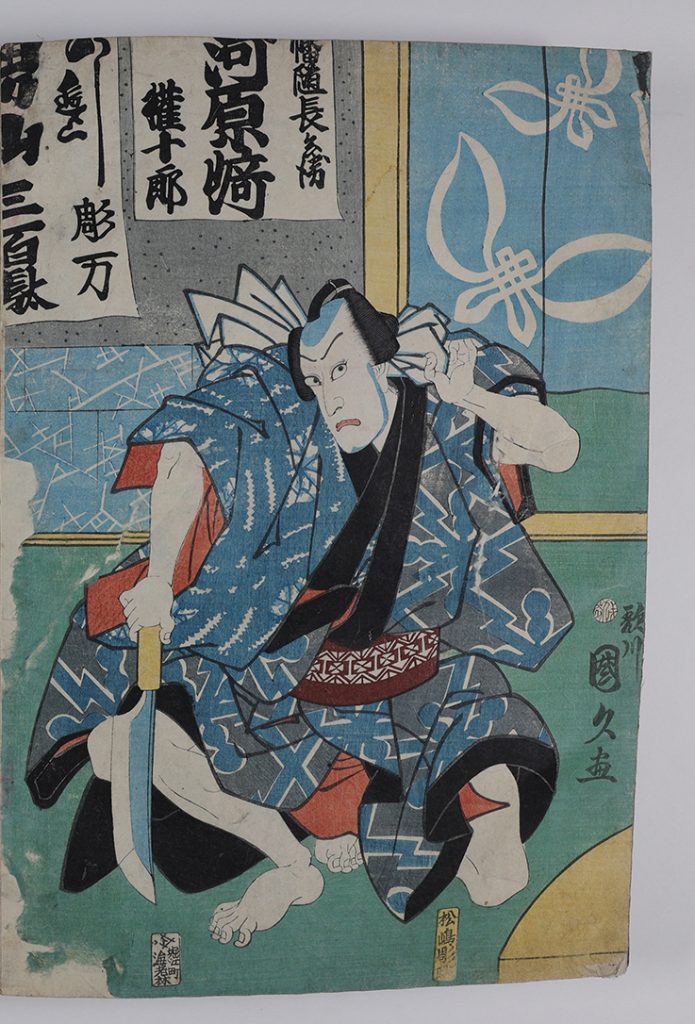

A scene from the play Banzui Chōbei’s Vegetarian Chopping Block (Banzui Chōbei shōjin manaita 幡随長兵衛精進爼板)1 with Nakamura Shikan IV 四代目中村芝翫 as Teranishi Kanshin and Kawarasaki Gonjūrō I (later Ichikawa Danjūro IX 九代目市川團十郎) as Banzui Chōbei (1862)

Ink on mulberry paper with mica powder

Seals:

Publisher: Ebiya Rinnosuke 海老屋林之助

Censor: Aratame 1862-IX

Artist: plate 11 signed “Ichiryūsai Kunihisa,” plate 12 signed “Utagawa Kunihisa”

Engraver: Matsushima Masakichi 松島 政吉

Sakurada Jisuke’s 1803 kabuki play Banzui Chōbei’s Vegetarian Chopping Block (Banzui Chōbei shōjin manaita)2 portrays wealthy samurai Teranishi Kanshin 寺西閑心 as engaged in a battle of honor against rival Banzui Chōbei 幡随長兵衛 (alt. Banzuiin Chōbei/Chōbē 幡随院長兵衛). Kanshin’s follower Dotesuke is injured while fighting with Chōbei’s young son. As revenge, during a family memorial service at Chōbei’s home, when only vegetarian cuisine is permitted, Kanshin delivers Dotesuke posed in the shape of a fish on a chopping block. Chōbei initially responds by pretending he will cut Dotesuke into sashimi, but he then places his own child on the chopping block instead, allowing Kanshin to determine the appropriate punishment for his previous transgressions. Chōbei’s actions ultimately inspire such respect in Kanshin that the two agree to overlook their quarrel and become allies.3

In this diptych, Kunihisa depicts the climax of the action, capturing the moment that Kanshin, portrayed by actor Nakamura Shikan IV (1830-1899), begins to draw his sword while peering down at the writhing child on the chopping block, preparing to exact his retribution. The ominous skulls decorating Kanshin’s deep blue kimono intensify the anticipation in Chōbei’s sideways glance at his son from the opposing plate. Chōbei, portrayed by then Kawarasaki Gonjūrō I (1839-1903),4 perches gingerly on one knee, with an exaggerated sashimi knife still dangling from one hand recalling his earlier threat, while his other hand grasps at a white fan of fabric jutting from the back of his kimono.

There are myriad similarities in this Kunihisa print and the 1850 Banzui Chōbei spreads of relatively contemporaneous print designers Utagawa Kuniyoshi 歌川国芳 (1797-1861) and Utagawa Kunisada II 歌川国貞 (1786–1865),5 offering insight on the training of Utagawa school artists and emphasizing the collaborative nature of their discipline.6 Kunihisa’s combination of disparate influences from both his master Kunisada’s spread7 and Kuniyoshi’s8 seems to situate this diptych as a study of the two,9 aimed at developing Kunihisa’s mastery of the trademark Utagawa design style.10 The cultivation of artistic lineage within the Utagawa school11 parallels the familial continuity and interconnectivity that defined kabuki theater, evidenced in comparison of the actors portrayed in Kunihisa’s print and those in the 1850 series.12 Understood in its context of commercial print culture, this diptych alone embodies many of the primary themes of artistic expression in nineteenth-century Japan.

Emily Hall

Architecture and the Built Environment

Class of 2024

Annotated Bibliography

Bell, D. R.. “Conformity and intervention: Learning and creative practice in Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Japanese visual arts,” The Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 52 no. 1 (2018): 1-21.

This article details the training methods used by the different visual schools in Japan. Information regarding the copyist training of woodblock print artists within the Utagawa school and its historic application provided the basis for the assertion that the Kunihisa print may have been a study after that of his master and father-in-law Kunisada and/or a collaboration with Kuniaki II. Additionally, the strict requirements surrounding the maintenance of the school aesthetic explain the similarities between the depiction of the actors’ faces among Kunihisa, Kuniaki II, and their master Kunisada.

Kincaid, Z.. Kabuki, the Popular Stage of Japan. The University of Michigan Press, 1925.

Though dated, this book presents a basic background on kabuki.

Leiter, S. L.. ““Kumagai’s Battle Camp”: Form and tradition in Kabuki acting.” Asian Theatre Journal, vol. 8, no. 1 (1991): 1-34.

This article provides a discussion of kata 形 (form), analyzing its origins, rigidity, and flexibility. Leiter cites the increasing presence of Western influence in Japan resulting in decreased popularity of traditional kabuki theater and the emergence of different kata (including acting, makeup, costumes, and props) in the realization of classic productions. Specifically, for the “Kumagai’s Battle Camp,” a scene of the play Ichinotani, the actors Ichikawa Danjurō IX and Nakamura Shikan IV were the sources of two different kata, marking them both as noteworthy figures in kabuki whose influences are still used as criterion for evaluating the production of this scene.

Mueller, L. J.. Competition and collaboration in Edo print culture: Lineage, creative specialization and market eminence for artists of the Utagawa school, 1770 – 1900 (Publication No. 3740998) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Wisconsin, Madison, 2015]. ProQuest.

Roberts, L. P.. A Dictionary of Japanese Artists: Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics, Prints, Lacquer. Weatherhill, 1976.

Shively, D. H.. “The Social Environment of Tokugawa Kabuki,” in Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader Account, ed. N. G. Hume. SUNY Press, 1995, 193-235.

Thompson, S. E.. Utagawa Kuniyoshi: The sixty-nine stations of the Kisokaidō. Pomegranate, 2009.

Tinios, E. (1991). Kunisada and the Last Flowering of “Ukiyo-e” Prints. Print Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 4 (1991): 342-62.