Plates 115-117: Meeting of loyal retainers in Oribe house

Plates 115-11: Meeting of loyal retainers in Oribe house

Utagawa Yoshitora (歌川 芳虎) (act. ca. 1836-1887)

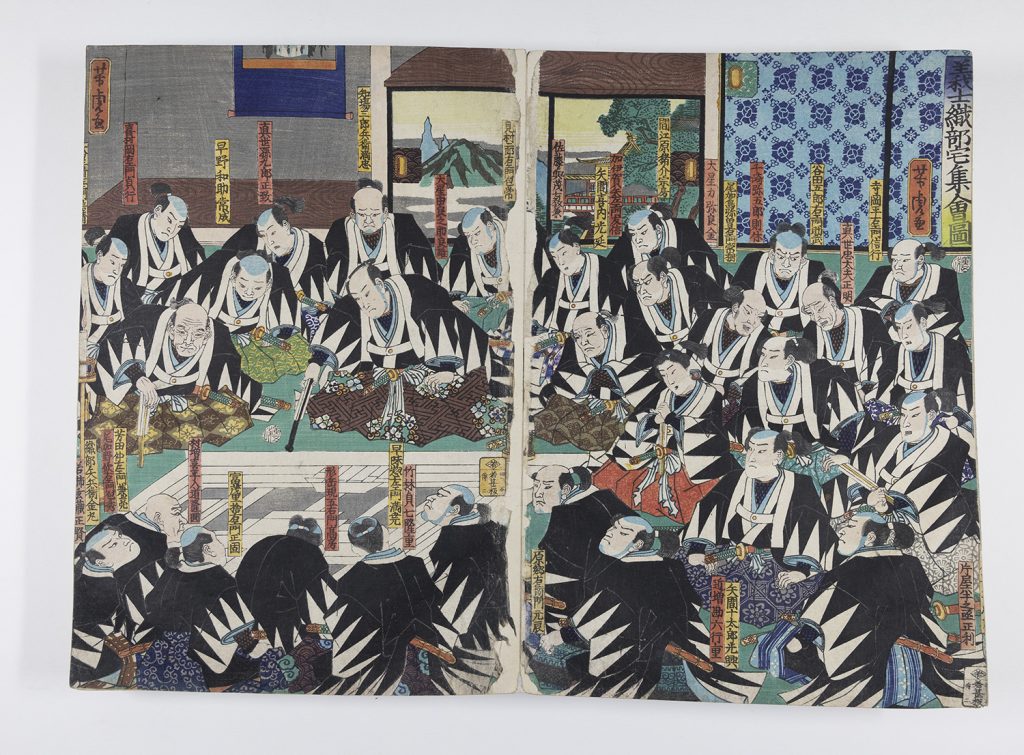

Meeting of loyal retainers in Oribe house (Gishi oribe taku shūkai zu 義士織部宅集会図)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Wakasaya Yoichi

Censor: Aratame 1866-V

Carver: Unknown

Artist: Utagawa Yoshitora (歌川 芳虎)

In this striking triptych by Utagawa Yoshitora, forty-seven samurai are gathered around a map clearly engaged in an intense discussion of their future plans. To any viewer of the time, the number of men as well as their iconic black-traingled attire would have immediately signaled this as a scene from the Chūshingura.1

The Chūshingura (The Loyal 47 Rōnin), is a popular kabuki play adapted from a ningyō-Jōruri (puppet play) co-written by Takeda Izumo, Namiki Sosuke, and Miyoshi Shoraku. 2 Speculatively based on real events that took place starting the spring of 1701 and unfolded over the next two years, this play follows a group of masterless samurai, or rōnin. In the historic event, the forty-seven rōnin — led by Oishi Kuranosuke (1659-1703) — beheaded Kira Yoshinaka (1641-1703) after he got their master, Asano Naganori (1667-1701), sentenced to death by seppuku, a type of “ritual suicide.” 3 The resulting play, which was written only forty-five years later, follows a dramatized narrative of forty-seven rōnin who try to avenge their master Enya Hangan after he is sentenced to seppuku following a conflict with a man named Moronao. 4 In 11 acts, the play explores themes of loyalty, honor, revenge, love and pride.

The depiction of plays, especially one as well-known as Chūshingura, was a popular tradition in ukiyo-e prints of the Edo period (1603-1868). 5 For Utagawa Yoshitora, this print was an extension of two of his most explored subjects: prints of actors (yakusha-e) and warriors (musha-e). 6 In it, he captures the expression of each rōnin, or rather each actor playing the rōnin, with painstaking detail. On the far left of the middle print, an older man scrunches his face in concentration displaying the fine lines of his wrinkled visage. Near the top of the rightmost print, a man scowls as he looks at the map, his eyebrows knitted together, his mouth downturned, and his eyes flashing with anger. The strong feelings expressed through facial features — ranging from anger to sadness, from surprise to determination — mimic the emotive and complex themes of the play.

This sense of chaos and clashing interests is furthered through the competing color composition of the print. While the color palette creates a slightly cool-toned focus by featuring light blue stubble, dark blue wall patterns, and turquoise-green floors, there are also many warm toned accents, such as the bright orange-red pigment in the samurai clothing and swords, and the yellow and orange cartouches with character names. The patterns, too, compete with each other for attention; for example, the samurai’s Hakama (loose fitting pants) as well as the sliding door paintings of landscapes and patterns feature different complex yet contrasting designs.

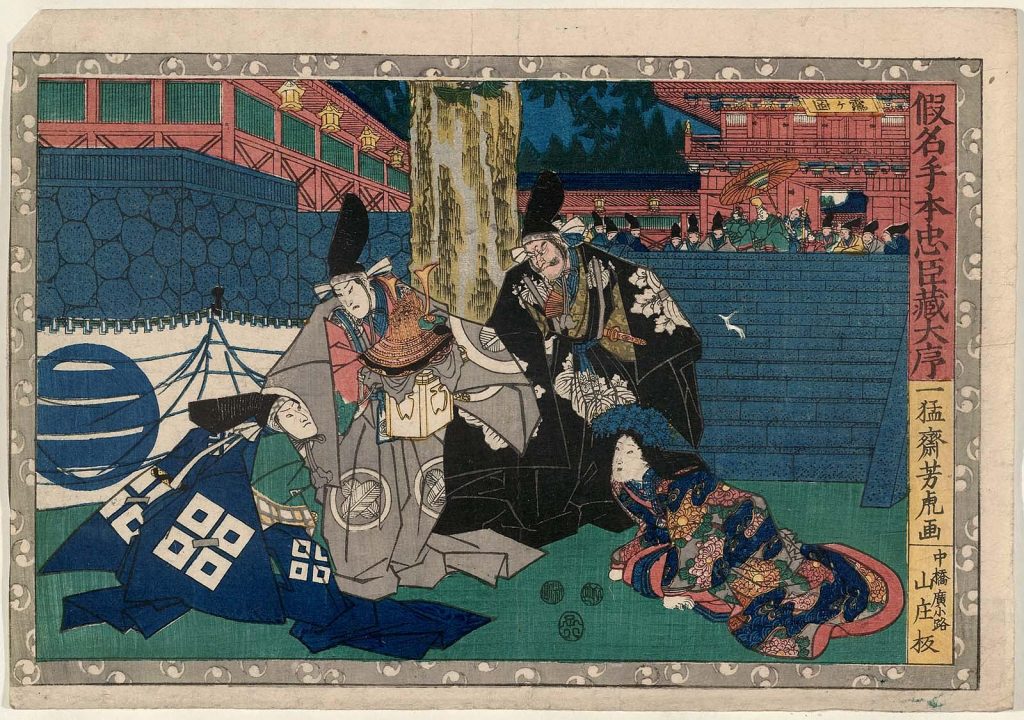

Although there is not much biographical information on the artist Utagawa Yoshitora, we know from the extensive collection of his work that has been preserved and made available, that the Chūshingura was a much-revisited subject for him. 7 In addition to this work, he also completed a print on the night attack scene from Act 11, which had famously been drawn by his mentor Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), and created prints for a series called The Store House of Loyal Retainers, a Primer.

Ben Hayden

Art History and Political Science

Class of 2024

Annotated Bibliography

Fleming, William. “Restaging the forty-seven rōnin: Performance and print in late eighteenth-century Japan.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 48 (2015): 391-415.

This article examines the popular play Chūshingura, how it portrays the forty-seven rōnin, and how the play has influenced Japanese print depictions of the forty-seven rōnin.

Foxwell, Chelsea. “The Double Identity of Chūshingura: Theater and History in Nineteenth-Century Prints.” Impressions, no. 26 (2004): 22–43.

In this article, Foxwell exploresthe dual function of the Chūshingura as a re-telling of a historic event and a dramatized, and censored, Kabuki play. Specifically, she writes about how this phenomenon manifests itself in ukiyo-e prints, which drew both on Kabuki performances and real-life details.

Marks, Andreas, and Stephen Addiss. Japanese woodblock prints: Artists, publishers, and masterworks: 1680-1900. N.p.: Tuttle Publishing, 2010.

This book provides several-page histories for a variety of famous artists and publishers of ukiyo-e prints from 1680-1900; including a section on Utagawa Yoshitora.

Mueller, Laura Jean. “Competition and collaboration in Edo print culture: Lineage, creative specialization and market eminence for artists of the Utagawa school, 1770 – 1900.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (2015).

This dissertation explores Edo-period ukiyo-e prints, particularly those originating from the Utagawa school; it also investigates how the school and its members established a continuous artistic lineage that influenced prints of following generations. Utagawa Kuniyoshi is addressed, presenting a way to consider how his background and style influenced Utagawa Yoshitora.

Izumo, Takeda, Senryu Namiki, and Shoraku Miyoshi. Chūshingura: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers: A Puppet Play. Translated by Donald Keene. New York: Columbia University Press, 1971.

This book is an English translation by Donald Keene of the original text of the Chūshingura by Takeda Izumo, Senryu Namiki, and Shoraku Miyoshi. It also provides an introduction and notes with explanations of scenes and dialogue from the play.