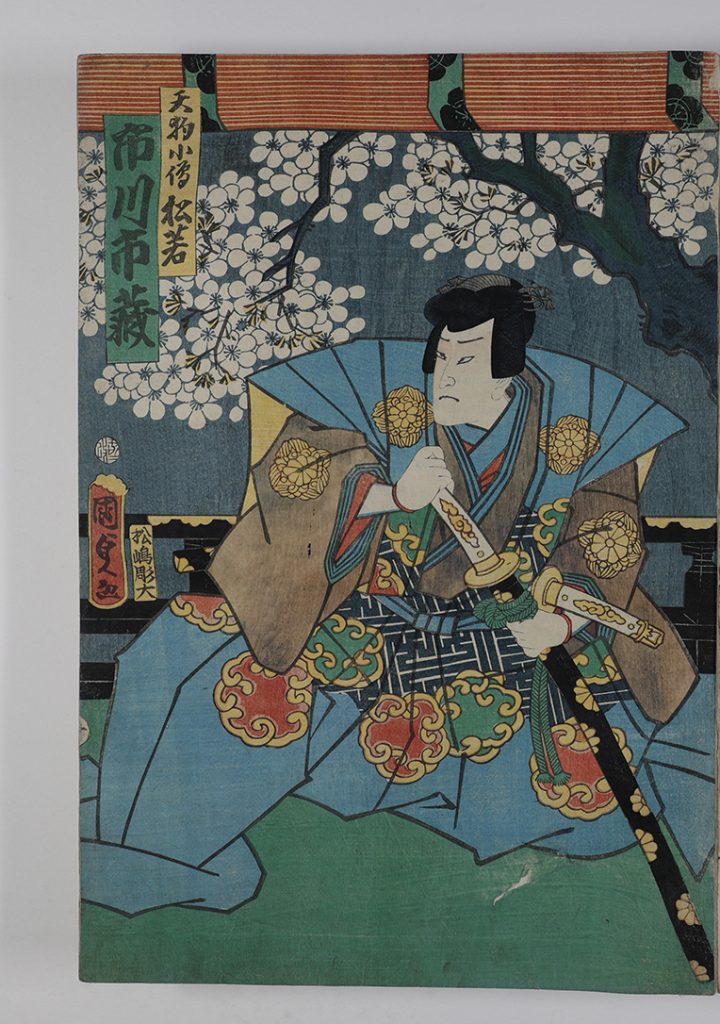

Plates 23-25: Triptych of kabuki actors Nakamura Shikan IV, Iwai Kumesaburō III and Ichikawa Ichizō III

Plates 23-25: Triptych of kabuki actors Nakamura Shikan IV, Iwai Kumesaburō III and Ichikawa Ichizō III

Utagawa Kunisada II (Toyokuni IV) (1823-1880)

Triptych of kabuki actors Nakamura Shikan IV, Iwai Kumesaburō III and Ichikawa Ichizō III from the play “Miyakodori Nagare no Shiranami 都鳥廓白浪” (The Great Thief of the Miyakodori Brothel) (1863)

Ink and color on paper, nikawa (animal glue)

Seals:

Publisher: Maruya Tetsujiro

Censor: Aratame – 1863 – II

Carver: Unknown

Artist: Unknown

This triptych portrays a scenic afternoon showcasing a moment of tension between three kabuki actors, Nakamura Shikan IV 四代目中村芝翫 (1831-1899) shown as the man in black robes, onnagata 女形 (male kabuki actor playing female role) Iwai Kumesaburō III 三代目岩井粂三郎 (1829-1882) shown as the central woman, and Ichikawa Ichizō III 三代目 市川市蔵 (1833-1865) shown as the man in blue robes.

The female character stands tall, her body positioned in a confident and graceful stance. Much of her bodily features are hidden beneath her elegant robes except the slight glimpse of pale wrist, which extends from within inner robes to grasp at a wooden stake. She wears outer robes decorated with delicate peonies and her sakko 先笄 hairstyle suggests a status as a married woman, which compliments her modest presentation and composure.1 Similarly, the attire of the men at her sides suggests their warrior status. The man in the black robes, played by actor Nakamura Shikan IV, is identified as a common samurai warrior by his traditional chain mail clothing. The man in the blue robes is identified as a higher-ranking daimyō 大名 (a feudal lord) due to his formal kataginu 肩衣 jacket and matching naga bakama 長袴 trousers in place of regular armor.2 Both male figures have similar hairstyles, common and popular amongst the warrior class during the Edo period (1603-1868).3

Nakamura’s samurai character, facing the central character, grasps the bottom of the signpost that extends towards the central female figure. This is complemented by the woman’s face being directed towards him as she clutches the other end of the wooden post. Although not physically touching, they share an intimate connection through this action of grasping the same stake. In opposition to this action, the daimyō, played by Ichikawa Ichizō III, solemnly stands behind the woman. Isolated, he stares almost longingly as his body faces almost entirely in her direction. He clenches at the hilt of his sword as he gazes at her but appears unable to take part in the moment between the other two characters as she is faced away from him.

Unlike the emotional tension expressed within the three figures of the piece, the background landscape is quite harmonious. It is not strenuously at work and instead displays a serene evening sky paired with gentle cherry blossoms.4 The blue sky and the pale petals paint a balanced landscape that allows the viewer to freely experience the beauty of nature in contrast to a delicate relationship playing out on the “stage” of a veranda, a further visual reference the theatrical aspect of the prints’ subject matter.

Michelle Kwon

History of Art & Neuroscience

Class of 2023

Bibliography

Meech-Pekarik, Julia, and John T. Carpenter. Designed for Pleasure: The World of Edo Japan in Prints and Paintings, 1680-1860 ; Issued in Connection with an Exhibition Held Feb. 27 – May 4, 2008, Asia Society and Museum, New York, New York. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008.

This source discusses the multiple components of an ukiyo-e print, including popular artists, characters, and courtesans depicted as well information about publisher and patrons. This source is relevant because it is able to provide insightful background information on the Edo period and the influences of the time.

Ambros, Barbara. “The Edo Period: Confucianism, Nativism, and Popular Religion” in Women in Japanese Religions. New York: New York University Press, 2015: 97-114.

This source discusses the ways in which women of Edo Japan were viewed and treated. It includes important details about the life of married women and their societal expectations as well as women outside the patrilineal household such as courtesans. The source is particularly relevant because this print depicts a female character who at first glance, is expected to look like a courtesan, but is in fact a married women. Understanding a women’s roles and value in Edo Japan provides important details into understanding how and why an artist chooses to illustrate and portray women.

Kafū, Nagai, Kyoko Selden, and Alisa Freedman. “Selections from ‘Ukiyo-e Landscapes and Edo Scenic Places.’” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 27, no. 1 (2015): 175–83. https://doi.org/10.1353/roj.2015.0018.

This source discusses the various scenic details and landscaping choices that popular ukiyo-e artists utilize in their prints and explains in detail why certain details and ideas were conveyed through their various selections of natural elements.

Herwig, Henk, Paul Griffith, Robert Schaap, Sebastian Izzard, and Kunisada Utagawa. Kunisada: Imaging Drama and Beauty. Leiden, The Netherlands: Hotei Publishing, 2016.

This book discusses some details of Utagawa Kunisada I’s life and inspirations for his ukiyo-e prints during his time as head of the Utagawa school. It also goes into some details about his student as well. As the artist of this triptych is Kunisada II, student of Kunisada I, this source is relevant to the study of these prints in a larger artistic lineage.