Plates 95-97: Triptych of Chūshingurasa Scenes

Plates 95-97: Triptych of Chūshingura Scenes

Yōshū Chikanobu 楊洲周延 (Toyohara 豊原) (1838-1912)

Triptych of Chūshingura 忠臣蔵 scenes (1884)

Ink and color on paper

Seals: unknown

Publisher: Hasegawa Chūbei, Tokyo

Censor: none

Carver: unknown

Artist: Yōshū Chikanobu

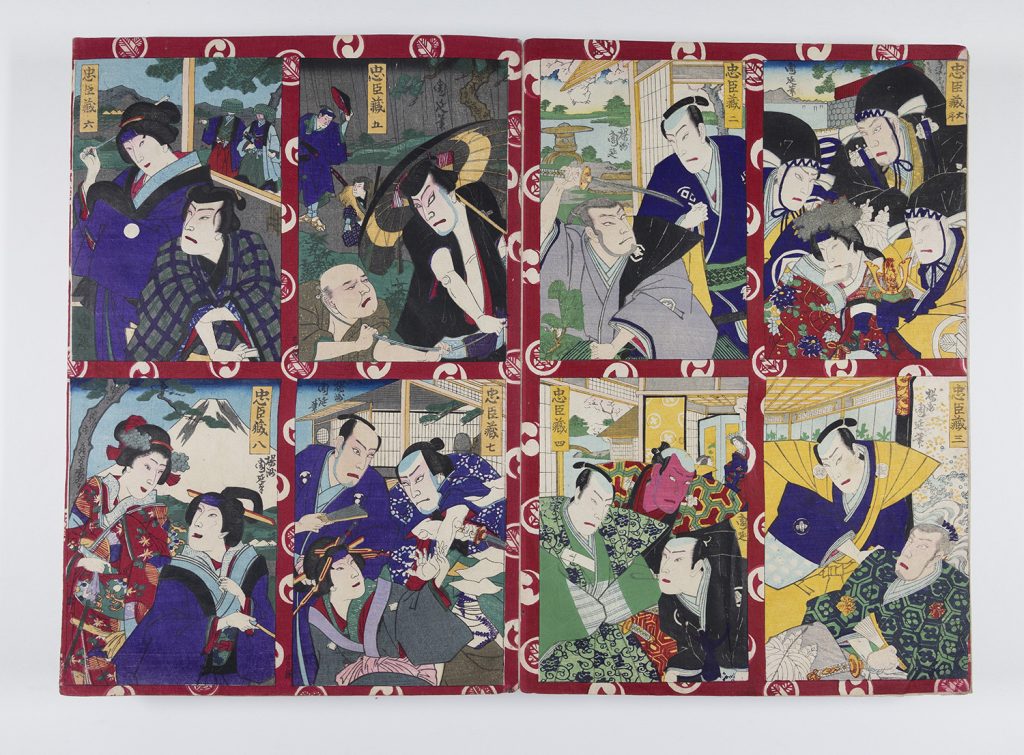

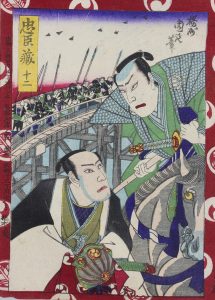

This triptych depicts scenes from Chūshingura (The Treasury of Loyal Retainers), one of the most popular and highly praised plays in the history of Japanese kabuki theatre. Brought on stage in 1749, the kabuki play alludes to an actual historical incident. In the spring of 1701, Asano Naganori, lord of Akō domain, drew his sword in a failed attack on Kira Yoshinaka, the shogun’s master of ceremonies, and was subsequently sentenced to death by seppuku 切腹 (a form of ritual suicide). Seeking revenge, forty-seven of Asano’s former retainers, now rōnin 浪人 (masterless men), attacked Kira’s mansion at night and beheaded him.1 This nighttime attack is captured in the play’s Act XII, depicted in Figure 1. The Akō incident soon reincarnated in various forms, including puppet and kabuki performances, paintings, and ukiyo-e prints. However, Chūshingura was rarely performed as the eleven-act play as it was first written, and a great number of variants appeared over time in response to the changing demand of audiences.2 This triptych, for instance, pictures a twelve-act reformulation of the original play.

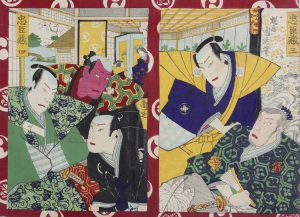

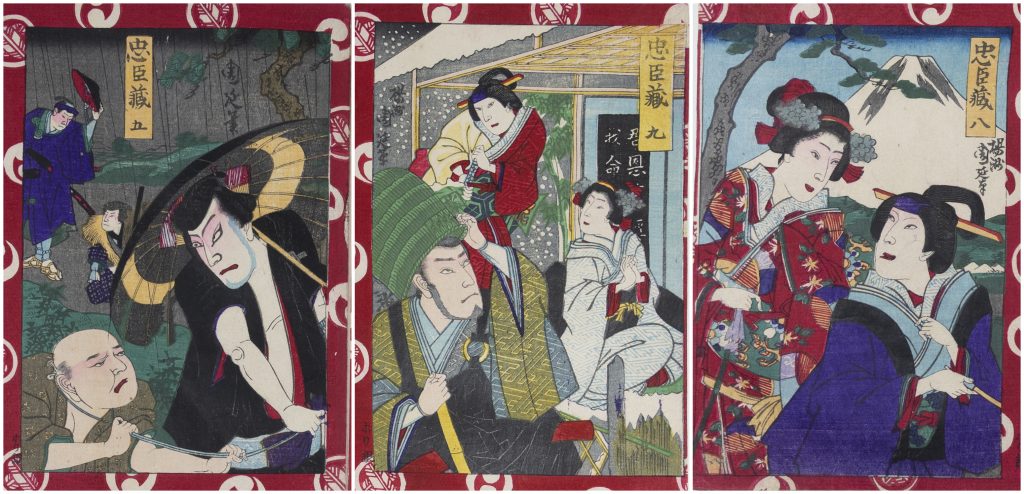

Different from earlier prints which were either monochromatic or hand-colored with a very limited color palette, this triptych has bright and vibrant colors, such as the red background surrounding the individual rectangle scenes, the pink face, and the yellow costumes, as shown in Figure 2. These colors most likely come from synthetic pigments. In fact, the Prussian blue used in some of the sky area would immediately date this print to after the 1820s, when the pigment was just imported from China and the West.3 The metallic effect on blades, hair ornaments, and hats – as in Figure 3 – was achieved by first painting the area with nikawa 膠 (animal glue) and then sprinkling metallic powder over the print. Nikawa was also applied together with sumi 墨 (black ink) to create a lacquer feel on black clothes.4 This print therefore presents the rich set of materials and techniques available to ukiyo-e designers in the mid-nineteenth century.

Yōshū Chikanobu (1838-1912), whose personal name was Hashimoto Naoyoshi, was most famous for his nishiki-e 錦絵 (brocade prints) and was a master of bijinga 美人画 (beautiful women pictures). He had studied painting with the Kanō school as a child and later changed to woodblock prints. In 1862, he entered the school of Toyohara Kunichika (1835-1900), who was noted at that time for actor prints. Over the next three decades, Chikanobu created large volumes of kabuki actor prints, but his style shifted significantly. His prints from the 1870s to the 1880s were mostly advertisement posters pictured in stage settings, but his prints of the 1890s had their characters presented in rather realistic settings with narrative compositions.5 In fact, his personal style already began to shine in this 1884 triptych. Though with a classic stage set for some of the scenes, the more naturalistic depiction of landscape – the rain, the snow, and Mount Fuji in Figure 2, for example – brings the viewer to the time and place where the Akō incident actually happened. Moving beyond the stage, the prints allow for a double reading as both stage performance and commemoration of history.6

Mengyu Yang

Economics, Mathematics

Class of 2023

Annotated Bibliography

Brandon, James, ed. Chūshingura: Studies in Kabuki and the Puppet Theater. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1982.

This book brings together four papers that describe how the historical Akō vendetta of the early eighteenth century was brought on stage under government censorship. The book concludes with the text of The Forty-Seven Samurai, accompanied by kabuki and jōruri performance photos. The text of the play is especially helpful to identify the kabuki scenes pictured in this triptych.

Coats, Bruce, ed. Chikanobu: Modernity and Nostalgia in Japanese Prints. Leiden: Hotei, 2006.

This book is a survey of the life and career of the artist Yōshū Chikanobu. The book assembles a chronological collection of prints, illustrations, and paintings by Chikanobu with detailed annotations. It also compares and comments on his evolving artistic styles and helps explain the changes by noting the social context of Tokyo during the Meiji period. This book provides the personal background of the artist during the time this Chūshingura triptych was published.

Foxwell, Chelsea. “The Double Identity of Chūshingura: Theater and History in Nineteenth-Century Prints.” Impressions, no. 26 (2004): 22–43.

This article presents how the kabuki prints in the nineteenth century commemorate the Akō incident, which is concealed in the kabuki play, by merging stage and historical elements through visual means. The article also analyzes the stylistic development of kabuki prints during this period and how it was pushed forward by different schools of artists. This article provides insights into how this late nineteenth-century Chūshingura triptych differs from earlier prints and the interplay between kabuki performances and prints during the Meiji period.

Tucker, John. The Forty-Seven Rōnin: the Vendetta in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

This book provides accounts of the Akō vendetta and its afterlife in history by citing text documentation. One of the chapters dives deep into the social contexts and discusses act by act how the kabuki performance depicts but differs from the actual tragedy. The book details the true story behind each character depicted in this triptych and helps the understanding of the historical background as a whole.

Withycombe, Celia. “The Production of Ukiyo-e Prints.” In Prints of the Floating World: Japanese Woodcuts from the Fitzwilliam Museum, edited by Craig Hartley, 16-22. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum in association with Lund Humphries Publishers, 1997.

This article is a comprehensive discussion of the techniques and materials used in ukiyo-e prints over time. It helps to explain the process of achieving the various artistic effects in this triptych.