Plates 98-100: Famous ink paintings rivaling women

Plates 98-100: Famous ink paintings rivaling women

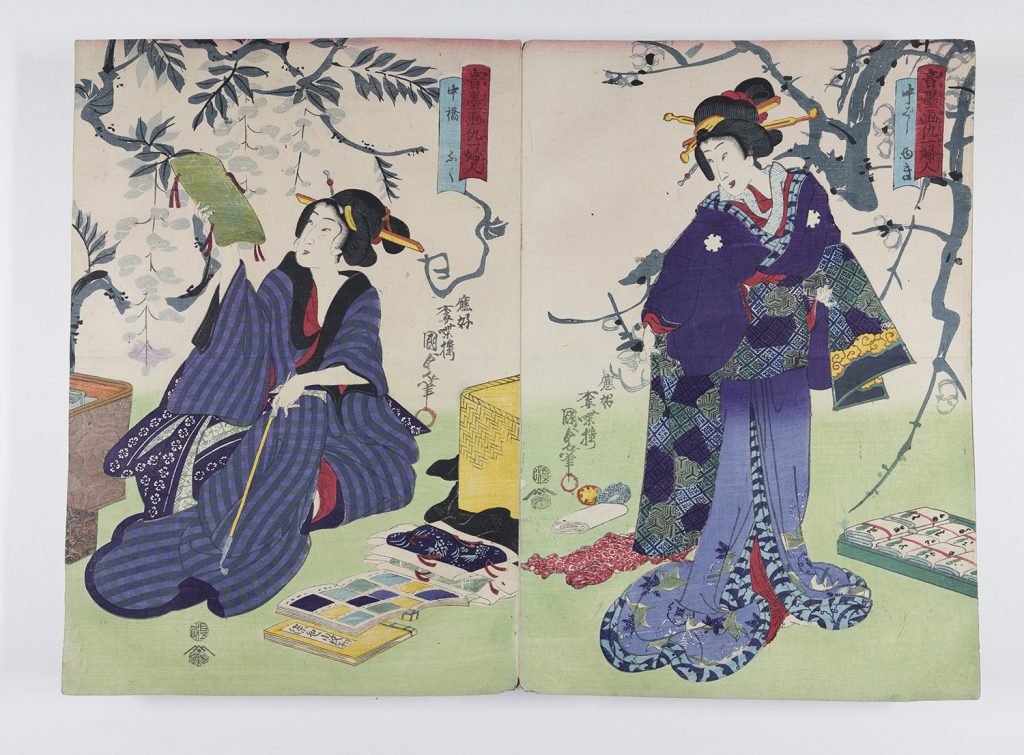

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823 – 1880)

Famous ink paintings rivaling women 音墨画仇一婦人 (1869)

Ink and color on paper

Seals:

Publisher: Tsutaya Kichizō

Censor: Aratame 1869-V

Carver: Unknown

Artist: Kunisada II

Kunisada II (1823 – 1880) was a student of Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865), one of the most successful ukiyo-e print makers of his time. Kunisada was greatly respected as a print designer and by his students of the Utagawa school for his ability to capture distinctive Japanese cultural symbols, such as courtesans or Kabuki theater actors, in his work. 1 The relationship between student and master was very close during Edo (1603 – 1868) and Meiji (1868 – 1912) periods, and artists often required a long period of apprenticeship under an already established print maker. Membership to an art school was a condition to entering the art world. 2 While less is known specifically about Kunisada II, a level of conformity under the style of a print studio was standard practice. Scholars can see this bond with the themes embedded in the art produced by Utagawa Kunisada and Kunisada II. Both Kunisada and Kunisada II often depicted Kabuki actors and women of the pleasure districts in their prints with notes of other classic Ukiyo-e stylistic elements.

Within the series, each print features a woman, likely courtesans, that worked in the pleasure districts. The woman in the middle print is tying her obi in the front, a clear signifier of courtesan attire. They are all wearing beautifully detailed kimonos and surrounded by packages of fabrics, color palette books and other textile items. One theme of Kunisada prints was to portray Edo Fashionistas. 3 These prints were commonly used to showcase new textiles and the latest fashion trends. This expanded the customer range of the prints as men could enjoy them as pinups and women for fashion inspiration. 4 There are other works by Kunisada II with the same title depicting very similar women and features suggest these prints are not a triptych, a collection of three prints, but belong to a larger collection of Edo fashionista prints. From the prints the women are not seamstresses but rather modeling the clothes and in a creative state of fashion design. One woman is holding up a textile and another is writing intensely with an already crumpled and dissatisfied piece of paper in her mouth. While these women may be courtesans, their body language in these prints can remind a modern viewer of a fashion magazine. The entire series may not be as focused on Edo Fashionista as these three prints but this theme could explain why they were collected together.

The vibrant blue of the kimonos, especially the woman in the first print, hints to the late Edo and Meiji periods’ introduction of synthetic pigments. The introduction of Prussian blue, a synthetic print color, allowed for a deeper and more vibrant color in woodblock prints. 5 These synthetic dyes that were imported from Europe describe an unexplored palette of colors shaping a new look to ukiyo-e prints. 6 The date of these prints also indicate a moment in the art world where synthetic dyes were used to create more vivid coloring.

The background of the prints is a reference to Japanese sumi-e paintings. Sumi paintings were a style of brush painting that used black ink to illustrate landscape or flora compositions. The trees in the background of these prints are common to Japan such as the Japanese maple tree or a cherry blossom. This additional element to the prints could be a mark of season. Both the Japanese maple tree and cherry blossom bloom in the springtime, between May and June and if this association with particular tree blooms and fashion trends is accurate it is a unique channel for telling the story of these prints. The intersection of these two artforms is complex and really beautiful.

Meredith Salmon

Anthropology

Class of 2023

Annotated Bibliography

Bell, David Raymond. “Conformity and Invention: Learning and Creative Practice in Eighteenth-and Nineteenth- Century Japanese Visual Arts.” Journal of Aesthetic Education, 52, no. 1, (spring 2018); 1-8.

Wang W, Zhang X, Liu Q, Lin Y, Zhang Z, Li S. “Study on Extraction and Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoids from Hemerocallis fulva (Daylily) Leaves.” Molecules, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27092916.

Zhao’s dissertation dives into the history of famine plant manuals in Ming-Qing China and Tokugawa Japan as an important and not-for-profit circulation of information for people to use when experiencing food shortages. Zhao describes how the writings started in China but were brought to Japan before Japanese herbalist began creating their own that included plants indigenous to Japan. The dissertation mentions Sakamoto Kōnen and his father Sakamoto Jun’an as physicians and herbalists who created text manuals on famine relief, specifically mentioning one created in 1836 titled 「救荒便覧」(A Handbook on Famine Relief).

Wang W, Zhang X, Liu Q, Lin Y, Zhang Z, Li S. “Study on Extraction and Antioxidant Activity of Flavonoids from Hemerocallis fulva (Daylily) Leaves.” Molecules, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27092916.

Cesaratto, Anna, Yan-Bing Luo, Henry D. Smith, and Marco Leona. “A Timeline for the Introduction of Synthetic Dyestuffs in Japan During the Late Edo and Meiji Periods.” Heritage Science 6, no. 1 (2018): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-018-0187-0.

This is a source from Heritage Science and examines the introduction of synthetic dyes during the Meiji Period and the changes to the aesthetic of woodblock prints. The deep blues on the kimonos worn by the women in my print analysis are very pigmented and with regards to their date it is likely they were colored with Perussian blue and or synthetic dyes. This was a sharp contrast to the muted tones of natural dyes but the result is a level of vibrancy that shouts from the paper.

Thompson, Sarah E. Kuniyoshi Kunisada. Boston: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts, 2017.

This literature source is from the MFA Boston and reviews the themes of Kuniyoshi and Kunisada block prints. The section I will be working with is on Edo period fashionistas. My prints draw the viewer to the beautifully intricate details on the kimonos that the central figures are wearing plus other textile items scatter the setting. Depictions of young women in the latest outfits or fashion trends was common in this time period. It widened the range of consumers as women would use them for style inspiration and men enjoyed them as pinups.

Schaap, Robert, et al. Kunisada : Imaging Drama and Beauty / Robert Schaap ; with an Introduction by Sebastian Izzard and Contributions by Paul Griffith and Henk J. Herwig. Hotei Publishing, 2016.

This book is focused on Utagawa Kunisada, predecessor to Kunisada II. Most of the publication is showing Kunisada’s ability to capture Japanese culture in his prints. There’s an emphasis on Kabuki actors and women from the pleasure districts. I will be using this source more for reference of the style of Kunisada, considering that this is where Kunisada II learned his skills and abilities.