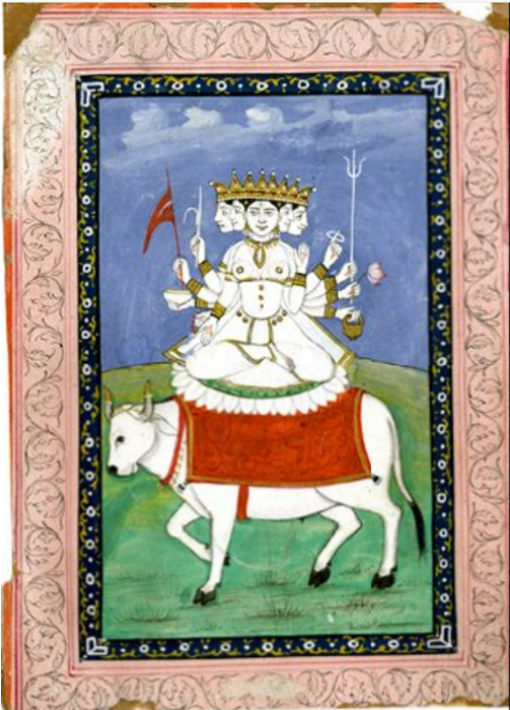

Parvati on Nandi

Parvati on Nandi

Parvati on Nandi

1800 CE

Tempera on paper

6.25 in x 4.25 in

India

1971.068

Parvati on Nandi is an Indian miniature painting that depicts two Hindu deities in Parvati, the goddess and consort of Shiva, and Nandi, the sacred bull.1 The central figure with multiple limbs, or Parvati, and the bull she is sitting on, Nandi, are both intimately tied with Shiva, the god of destruction.2 Shiva holds great importance within Hindu mythology as part of the Hindu Triad responsible for creation, preservation, and destruction.3 Shiva features in multiple Hindu mythologies, but the most relevant to the painting is one depicting his relationship with Parvati. Before becoming Shiva’s consort, Parvati took the form of Sati, who gave up her life to reincarnate as Parvati and unite with Shiva due to her father’s disapproval.4 It is important to note the concept of reincarnation in Hinduism in which there is no true death but a continuous cycle of birth and rebirth.5 Despite its origins, Parvati and Shiva’s relationship is often described to be full of emotional strain, which is perhaps a more realistic portrayal of relationships.6

Parvati represents a variety of concepts, but she usually mirrors the ideas of Shiva shown by the trident that she is holding in the painting, which is a common symbol associated with Shiva that represents destruction.7 Similarly, Nandi holds close ties with Shiva as his animal form and mode of transportation.8 What is curious about this painting is the absence of Shiva. Usually, Parvati, Nandi, and Shiva are depicted collectively as Shiva serves as the bridge between the deities.9 However, the artist’s decision to focus only on Parvati and Nandi lends credence to perhaps a regional influence on Hindu mythology, focusing more on Parvati as an individual for ritualistic worship rather than as Shiva’s consort.

The background of Indian miniature paintings like Parvati on Nandi reaches far beyond their start in India. They were derived from Persian miniatures10 after Persian Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (971-1030) invaded India.11 Famous Persian miniaturist Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād (1455-1535) introduced highly expressive faces to the world of miniatures. Like with Parvati on Nandi, miniatures were typically fairly two-dimensional. Thus, many miniature paintings looked uniform without any particular emphasis,12 until Rizâ Abbâsi (1565-1635)13 popularized painting miniatures with touches of color. Many artists copied his style, resulting in a range of similar miniatures; even in this 19th-century painting, we can see these vibrant regions of color,14 in addition to borders which became more popular in post-16th-century Indian miniatures.15

When the Mughal army conquered India in the 16th century, ruling emperor Muhammad Akbar (1542-1605, r. 1556-1605) encouraged the arts. He had the best Indian painters work under him, using their talents to increase his power.16 Such incorporations of religious miniatures into political rituals were common.17 Miniatures could also be used as objects of worship in Hinduism. Despite clear stylistic differences between miniatures before and after the Mughal invasion, these paintings’ contents remained largely similar: many Indian miniatures showcased human subjects modeled after Hindu figures or, like Parvati on Nandi, represented the earthly experiences of Hindu gods themselves.18

Andrew Kim

Biological Science

Class of 2026

Megan Grosse

Math

Class of 2026

Annotated Bibliography

Artist Unknown. Parvati on Nandi. 1800 CE. Tempera on paper, 6.25 x 4.25 in. https://jstor.org/stable/community.26753763.

The image of a painting depicting the deities Parvati and Nandi was created by an unknown author in 1800 CE. While its origins are difficult to identify, Parvati in particular is a prominent figure within Hindu mythology as Shiva’s consort as well as Nandi who is intimately tied with Shiva as his sacred bull. What is relevant to note is the painting’s relatively small size as it is a miniature painting that originates from India. This painting was investigated thoroughly throughout this excerpt as both a miniature painting and a representation of the vast Hindu mythology.

Brend, Barbara. Islamic art, Harvard University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-674-46866-X, 9780674468665.

This book by Barbara Brend focuses primarily on the 17th-century to 20th-century developments of Islamic art. It discusses a series of Persian artists, including Rizâ Abbâsi, who was the Isfahan School’s most well-known Persian miniature painter during the late Safavid era. Abbâsi was key in developing a style of miniature painting with more emphasis and color, making him highly relevant to Parvati on Nandi.

Britannica Academic. “Shiva.” Accessed October 13, 2023. https://academic-eb-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/levels/collegiate/article/Shiva/68031.

This source from the Britannica Academic is a summary of Shiva, a prominent deity and god within Hindu mythology. The source presents essential information on his relationship with other deities such as Parvati, his consort. In particular, it provides information on common iconography of Shiva. Although the article does not provide a substantial amount of information, it is objective and succinct. Thus, this source was used to confirm and connect Shiva’s iconography back to the objects that Parvati is holding in the painting, particularly the trident.

Caughran, Neema. “Shiva and Parvati: Public and Private Reflections of Stories in North India.” The Journal of American Folklore 112, no. 446 (1999): 514–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/541487.

IThe journal article by Neema Caughran investigates the unconventional relationship between Shiva and Parvati and connects it to current relationships in North India. Caughran specifically presents examples within Hindu mythology that show a relationship filled with conflict despite their godly stature. This is mirrored in human relationships as women in North India are often treated as individuals of lower status compared to men. By introducing personal anecdotes as well as specific examples from Hindu mythology, the article provides an objective look into the complicated relationships in India both for deities and humans. This source was used to characterize Shiva and Parvati’s relationship to the reader.

Desai, Vishakha N. “Painting and Politics in Seventeenth-Century North India: Mewār, Bikāner, and the Mughal Court.” Art Journal 49, no. 4 (1990): 370-378. https://doi.org/10.2307/777138.

This art journal entry by Vishakha Desai discusses paintings in India and their relation to politics. Specifically, it talks about Rājput paintings, which are created in India for Hindu courts seeking to gain political power through artwork. In this way, Indian paintings of the miniature painting area were sometimes used for political rituals. This means that Parvati on Nandi having a political purpose is an idea that should be considered, especially given India’s political climate after the Mughal invasion.

Kelley, Charles Fabens. “Persian and Indian Miniature Painting.” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) 27, no. 3 (1933): 46–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/4103604.

This article discusses the stylistic origins of Indian miniature paintings, especially the Persian influences. It goes through the historical timeline associated with the spread of Persian painting styles in India, detailing some specific elements that carried into Indian miniatures and others that did not remain in the long-term. This is relevant to Parvati on Nandibecause it shows Persian influence and includes many of the elements that this article discusses.

Martin FR. The Miniature Painting and Painters of Persia, India and Turkey, from the 8th to the 18th Century … by F.R. Martin. B. Quaritch, 1912; 1912.

This book has a focus on Persian art, but it does discuss Indian miniature paintings a

well. It talks about materials used in these paintings and commonalities in their styles.

Parvati on Nandi shows many similarities to the stylistic tendencies discussed.

Nazim, M.; Bosworth, C. Edmund (1991). “The Encyclopedia of Islam, Volume 6, Fascicules 107–108”. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. VI. Brill. p. 65. ISBN 90-04-08112-7.

This encyclopedia by M. Nazim and Edmund C. Bosworth includes an entry on Yamīn-ud-Dawla Abul-Qāṣim Maḥmūd ibn Sebüktegīn, who is commonly known as Mahmud of Ghazni. He was a Persian Sultan who invaded India in 1001 CE. He is relevant to Parvati on Nandi because his invasion is the main reason that Persian miniature painting styles became so popular in India. Many of these Persian style elements are in Parvati on Nandi.

Thuruthiyil, Scaria. “Reincarnation in Hinduism.” Salesianum 60, no. 1 (January 1998): 35–63. https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdah&AN=ATLAiC9Y170724000536&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Scaria Thuruthiyil discusses an important aspect of Hinduism in reincarnation. The author introduces several aspects of Hinduism including karma to explain the continuous cycle of birth and rebirth. With its comprehensive description of reincarnation from sacred texts and Hindu terminology, it serves as a reliable gateway into this complex concept. This source was used to allow the reader to comprehend how Parvati was able to assume different forms even after death.

Wilkins, William Joseph. Hindu Mythology: Vedic and Purānic. Calcutta and Simla: Thacker, Spink & Co., 1913.

William Joseph Wilkins presents a comprehensive book on Hindu Mythology that compiles different mythological stories from various sources to present to Western audiences. It is reliable as it not only specifically states where certain mythologies and depictions originated from, but it also provides visual examples of deities to aid in the understanding of the reader. This source was used as a basis in providing religious context to the readers as it extensively narrates numerous mythological stories associated with Shiva, Parvati and Nandi.