Eave Tile with a Design of a Phoenix

Eave Tile with a Design of a Phoenix, from King Injo’s Tomb in Channung

Eave Tile with a Design of a Phoenix, from King Injo’s Tomb in Channung, Korea

1630 – 1740 CE

Ceramic

7 in x 5.75 in

Joseon Dynasty, Korea

1992.384

How does this intricate architectural element contribute to the veneration of a king?

This ceramic eave tile is believed to come from the tomb of King Injo (1595-1649 CE, r. 1623-1649 CE), the sixteenth of twenty-seven rulers of the Joseon (Chosŏn) Dynasty.1 It was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, enduring over five centuries (1392-1910 CE).2 King Injo was appointed in 1623, after a coup d’état and the exile of the fifteenth king. Inheriting a dynasty plagued by factionalism, King Injo worked to defend himself against domestic opponents. His disregard for foreign powers enabled two invasions by the Manchu people in 1627 and 1637.3 The Manchus had used fragmentation in both the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE) and Joseon dynasty to destabilize their opponents.

With the fall of the Ming dynasty at the hands of the Manchu, Joseon began to regard itself as the sole inheritor of Confucianism. Neo-Confucianism grew from the writings of Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) scholars, strongly informing political ideology and belief systems in Joseon.4 Joseon was a hereditary aristocracy, and laws and practices used neo-Confucianism to maintain social and class hierarchies.5 Included in these practices were four rites: capping, marriage, mourning, and ancestor worship.6 Ancestor worship established a lineage structure, giving members a sense of belonging in a familial order. Heredity was used to perpetuate social status, especially among the royal elite.7

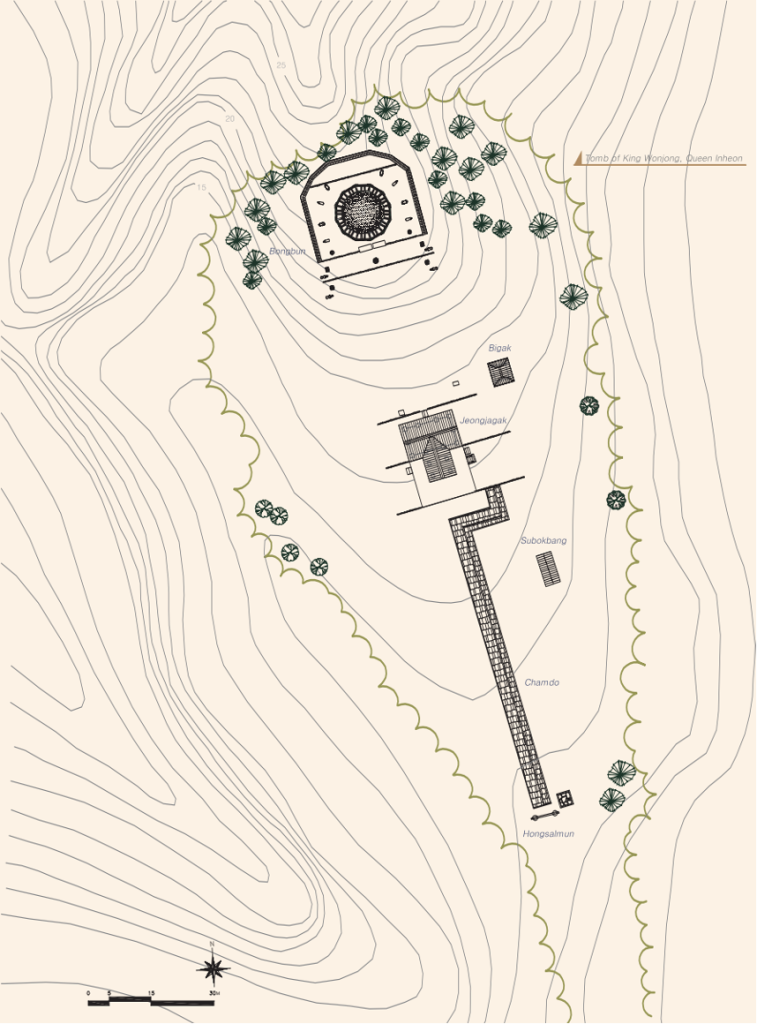

Labeled map of Jangneung. Cultural Heritage Administration. Nomination of Royal Tombs of the Joseon Dynasty for Inscription on the World Heritage List. UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1319/documents/.

The lane to the worship house. “WHATAWAYGOOK: Jangneung” https://whatawaygook.wordpress.com/tag/jangneung/ Accessed October 15, 2023.

King Injo’s tomb site, Jangneung, was moved and rebuilt in 1731.8 Enclosed by dense woods, the site is accessible only from one path, which leads to a jeongjagak shrine, the meeting point of the living and the dead. Ritual events performed today are held alongside the path or in the jeongjagak. The tomb rests atop a hill in front of the jeongjagak. It consists of a domed, joint tomb containing King Injo and his first queen, Queen Inyeol (1594-1636 CE). It is framed by a low stone wall and interspersed with stone structures and animal and human sculptures.9

The close-up image on the tomb site. “King Injo’s tomb now open to the public.” KOREA.net. Accessed October 15, 2023.

Interestingly, the tomb is not visible from the jeongjagak, creating a puzzling interplay between the tomb’s apparent invisibility yet clear presence. Perhaps the placement is intended to provide privacy to King Injo and Queen Inyeol. It is unclear where exactly the eave tile comes from. It could be part of the original tomb built at a different location in 1636, a part of the low wall, or a part of the jeongjagak roof.

Annual ancestral ceremony for King Injo at Jangneung. “King Injo’s tomb now open to the public.” KOREA.net. Accessed October 15, 2023.

Annual ancestral ceremony for King Injo at Jangneung. “King Injo’s tomb now open to

the public.” KOREA.net. Accessed October 15, 2023.

View from the jeongjagak. Google Earth (2019). Accessed October 15, 2023.

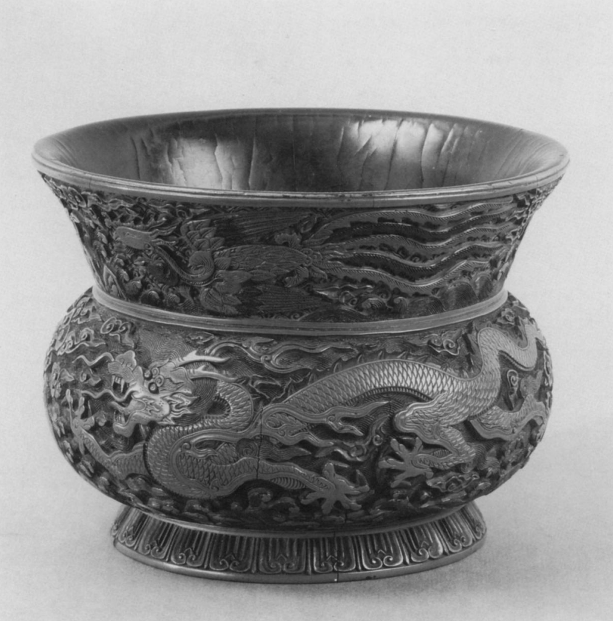

In traditional Chinese mythology, the phoenix was selected to represent Yin, as the counterpart of the dragon, which is Yang.10 This distinction was extensively used in representing royal power in East Asian art and rituals, with phoenix being the queen and dragon being the king.

A Ming (1368-1644 CE) lacquer Jar in the Form of a Grain Measure (Zhadou) decorated with Dragon and Phoenix. Wilson, J. Keith. “Powerful Form and Potent Symbol: The Dragon in Asia.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 77, no. 8 (1990): 286.

However, some evidence suggests that this tile’s depiction may not be a phoenix. Preceding the Joseon Period, in the Koryo Kingdom (918-1392 CE), detailed coffers in the royal burial chambers had figures of the Four Guardian Animals (四神 or sasin), one of which is the Vermilion Bird, often mistaken as a phoenix.11 In traditional Daoist Alchemy, the Vermilion Bird represents the spirit of heart. According to Daoist Alchemy, “to achieve physical and mental peace and calm one should be filial, loyal, just and kind-hearted”.12 These are values emphasized precisely in neo-Confucianism.

Appliqué figures of Four Guardian Animals. Charlotte Horlyck, “The Eternal Link: Grave Goods of the Koryŏ Kingdom (918–1392 CE),” Ars Orientalis 44, no. 20220203 (2014): 161.

The Vermilion Bird. Qicheng, Zhang, 張其成, Wang Jing, and 王晶. “Embodying Animal Spirits in the Vital Organs: Daoist Alchemy in Chinese Medicine.” In Imagining Chinese Medicine, edited by David Dear, Vivienne Lo, 羅維前, Penelope Barrett, Lu Di, 蘆笛, Lois Reynolds, Dolly Yang, and 楊德秀, 18:391. Brill, 2018.

While possibilities remain that the creature represents the Vermilion Bird, we surmise it is most likely a phoenix, as suggested by the absence of two Guardian Animals, the tiger and the tortoise, in other tiles. Yet despite this uncertainty and the nuance between Vermilion Bird and phoenix, it is known that both creatures are associated with longevity.1314Therefore, the presence of such symbols, with its strong association with the royal family, might shed light on Joseon’s visions of the afterlife. Moreover, the tiles, ubiquitous in Jangneung, perpetually reminded the visitors of the royal influence and turned Jangneung, an otherwise normal tomb, into a ritual space. Solemnly and silently, the visitors practice ancestor worship, extended through the entire Korean “bloodline” up to the royal family.

Kaiwen Shi

Computer Science and Math

Class of 2025

Laura Wan

Medicine, Health, and Society

Class of 2024

Annotated Bibliography

Bocci, Chiara. “The Phoenix (Feng 鳳).” In On Feathers and Furs: The Animal Section in Duan Chengshi’s 段成式<em>Youyang Zazu</Em> (ca. 853). An Annotated Translation, 37–39. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2bfhhkv.5.

Bocci in this short article explores an ancient Chinese text describing the form of a Phoenix and its auspicious functions. Then two external sources are cited to warn against the readers that Phoenix in Chinese mythology was more of a composition of various creatures instead of one long established entity with designated form.

Deuchler, Martina. “Neo-Confucianism: The Impulse for Social Action in Early Yi Korea.” The Journal of Korean Studies 2 (1980): 71–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41490153.

Deuchler uses this journal article to navigate the growth of neo-Confucianism in the early Joseon dynasty. She documents the shift from Buddhism under the Koryo Dynasty, and she describes how ancient models were taken and reworked. Deuchler dissects how neo-Confucianism was used to create mechanisms for interpersonal relations, power dynamics, and the preservation of a social order. This journal article is helpful in developing a critical understanding of neo-Confucianism and the extensive role it played in Joseon.

HORLYCK, CHARLOTTE. “THE ETERNAL LINK: Grave Goods of the Koryŏ Kingdom (918-1392 CE).” Ars Orientalis 44 (2014): 156–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43489802.

In this supplementary article, Horlyck presents an analysis of grave goods found in royal tombs and pit graves, offers a comparison between elite burial practices and those of the common people, and discusses the significance of them as burial objects. Horlyck also demonstrates that many of the burial practices, regardless of the social status of the dead, bore a resemblance to neo-Confucian paradigms described in Jia Li by Zhu Xi.

Palais, James B. “Post-Imjin Developments in Military Defense and Economy.” In Confucian Statecraft and Korean Institutions: Yu Hyongwon and the Late Choson Dynasty. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014. https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=1003033&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

The third chapter of Palais’ book provides an in-depth account of developments in Joseon following the Imjin War (1592-1598 CE). This chapter contextualizes the Joseon dynasty during a time where regional powers and conflicts among them greatly molded the political landscape of the kingdom. Focus was given mostly to details regarding the military and political decisions of the fifteenth and sixteenth kings of Joseon, Gwanghaegun and King Injo. Palais provides details that further illustrate how Joseon royalty is viewed in perpetuity.

Qicheng, Zhang, 張其成, Wang Jing, and 王晶. “Embodying Animal Spirits in the Vital Organs: Daoist Alchemy in Chinese Medicine.” In Imagining Chinese Medicine, edited by David Dear, Vivienne Lo, 羅維前, Penelope Barrett, Lu Di, 蘆笛, Lois Reynolds, Dolly Yang, and 楊德秀, 18:389–96. Brill, 2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs6ph.33.

Qicheng attempts to connect vital organs to animal spirits based on three most important books in Daoist canon. In this journal, Qicheng offers an extensive graphical illustrations of the animal spirits and explanations of their functions according to the three books in tabular form. It should be noted that the four guardian animals mentioned in our article are all present in Daoist Alchemy, though in slightly different forms. Phoenix, clearly differentiated from Vermilion Bird, is also described.

Wilson, J. Keith. “Powerful Form and Potent Symbol: The Dragon in Asia.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art77, no. 8 (1990): 286–323. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25161297.

Wilson notices the significance of the Dragon image in Asian arts, and formulates a considerable amount of theories on why the dragon is so important in Asian culture. He includes many examples of dragons, spanning from a vessel, an inscription, to a wine warmer or a bell. Phoenix themes are also represented in the examples, from which we can learn more about Phoenix in Asian arts.