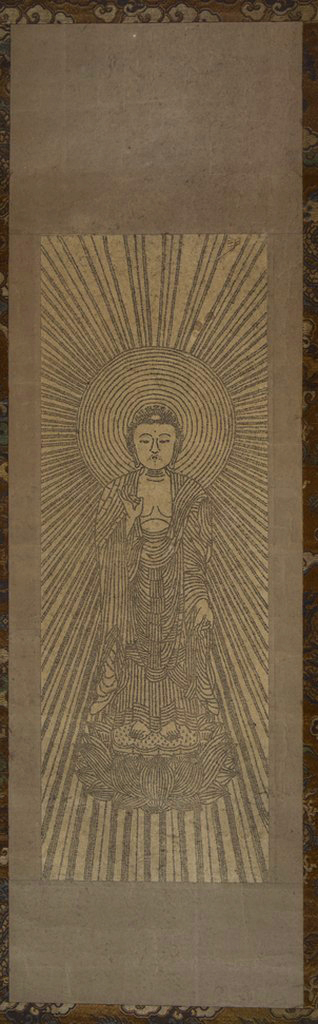

Amida Hanging Scroll

Amida Hanging Scroll

Amida Composed of Chinese Characters

ca. late eighteenth to early nineteenth century

Ink on paper

19 3⁄4 × 6 7⁄8 × 13 1⁄4 inches

Japan

1999.140

Befitting his title as the Buddha of “Immeasurable Light,” in this hanging scroll, Amida is adorned by a halo and emitting rays of celestial light. He stands tall upon a lotus blossom, hands fixed in the gesture of gebon geshō that is symbolic of his warm reception of devotees into the lowest level of his Land of Utter Bliss.1 Shifting the gaze further upwards reveals a rounded face with soft features bracketed by extended earlobes that are a testimony to his princely virtue. Amida’s eyes are half closed in meditation, and in the painting’s original suspended state, he would have appeared like a divine vision answering the callings of his pious believers.

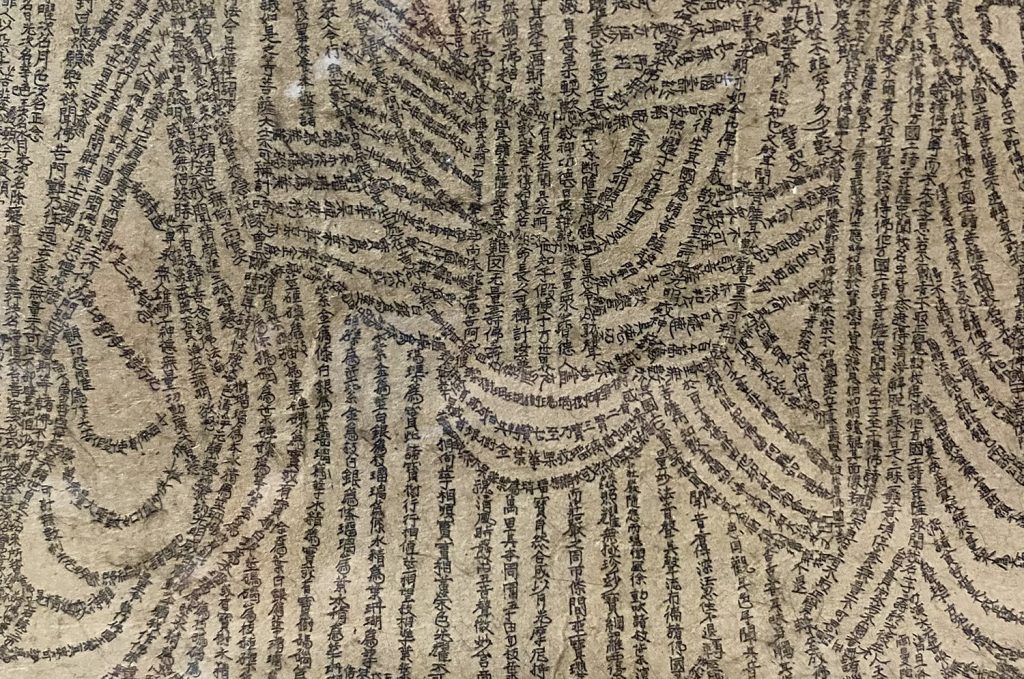

A closer examination of the artwork reveals that what appear to be solid brush strokes composing the buddha’s form are, in reality, minuscule Chinese characters. At least some of the characters are from the Sutra on the Contemplation of Amitayus (Skt. Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra, Ch. Kuan wu-liang-shou fo ching 佛說觀無量壽佛經, J. Bussetsu kanmuryōjukyō 仏説観無量寿経), a crucial scripture of the Pure Land School of Mahayana Buddhism.2 This sutra lays out the Buddha’s instruction of sixteen graded visualizations, which mainly include Amida, his Bodhisattva attendants, and his Pure Land world. According to the text, one could attain these visualizations through firm faith, filiality, compassion, and the ten good actions, and they will eventually enable the practitioner to be reborn in the Pure Land.3 This scroll visualizes the content of the sutra and, more importantly, the teaching of the Buddha by transcribing the scripture in the figural shape of the Amida Buddha. By the twelfth century, the prevalence of Pure Land Buddhism had transformed the Japanese religious landscape into one that was more inclusive across social class. No longer was Japanese Buddhism “a superficial, theurgic cult”4 practiced by the aristocracy to fulfill their utilitarian needs. Increasingly among commoners were holy men who urged believers to reject their unenlightened, worldly reality and seek salvation by rebirth into Amida’s Pure Land.5

This artwork belongs to the dharma relic category of objects, which represents a conflation of the Buddha and his teachings. In other words, the Buddha’s words become relics. Such a concept of the equivalence between the Buddha and his dharma (teachings, doctrine) can be found in many Buddhist texts. For instance, the Lotus Sutra, one of the most important scriptures in the Buddhist canon, writes that “a man…who shall look with veneration on a roll of this scripture as if it were the Buddha himself.”6 The Diamond Sutra similarly says “from the Dharma should one see the Buddhas.”7 The scroll embodies the dharma relic simultaneously in written and figural forms. In this way, the scroll explicitly illustrates the concept of the dharma relic by facilitating relic veneration through identifying the sutra/teachings with the body of Buddha.

Jiawei Wang

Neuroscience | History of Art | Medicine, Health, and Society

Class of 2023

Xuliang Zhang

Economics | History of Art

Class of 2023

Annotated Bibliography

Andrews, Allan A. “World Rejection and Pure Land Buddhism in Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 4, no. 4 (November 1, 1977). https://doi.org/10.18874/jjrs.4.4.1977.251-266.

By the twelfth century, Pure Land Buddhism had converted the Japanese religious landscape into one that is “authentic” and inclusive of all social classes, the folk as well as the elite. “Authentic” Buddhism is defined as the rejecting worldview seen in Early Indian Buddhism where both the unenlightened individual and their experience are rejected. This contrasts starkly with the Shinto tradition before the dominance of Pure Land Buddhism, where the natural environment and human communities were thought to be ultimately fulfilling. Although the Amida scroll painting was created long after this period in Japanese history, understanding this transition helps to better position the artwork in its religious narrative.

O’Neal, Halle. Word Embodied: The Jeweled Pagoda Mandalas in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1st ed., 412:168–192. Harvard University Asia Center, 2018.

This article examines the history, types, and function of single-sheet Buddhist woodblock prints. The author first recognizes the lack of systematic research done on this topic because of the brittle form of these prints that make them harder to be handed down as well as the lack of clear contextual information denoted on these objects. Still, a comprehensive study of this subject matter would be valuable in revealing social trends of the worship of Buddhism within the more ordinary public, since many iconographical subjects of these prints are temporal and shift with changes in social preferences. The paper also discusses two main functions of single-sheet woodblock prints for protection and worship, which are to serve as talismans and to act as a visual aid in place of larger and less accessible Buddhist paintings.