Japanese Buddhist Print (Ofuda)

Japanese Buddhist Print (Ofuda)

Japanese Buddhist Print (Ofuda)

18th-early 20th century

Ink on paper

12 x 5 inches

Japan

1988.049

Image Description

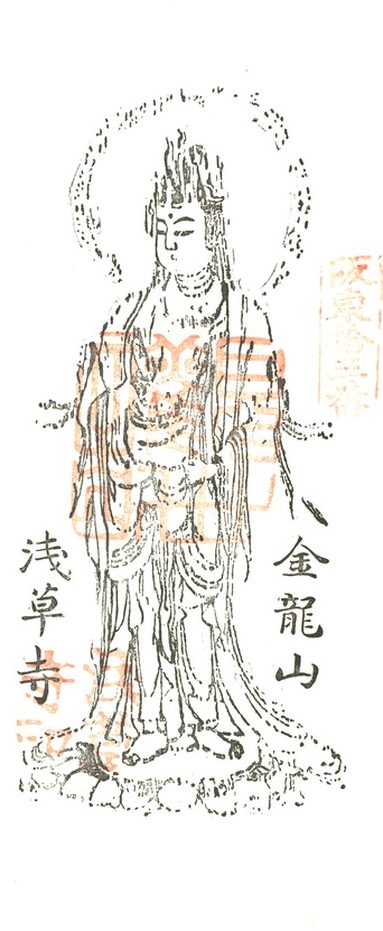

This print depicts Kannon (Sanskrit: Avalokiteshvara), the bodhisattva of compassion and a popular deity in East Asian Buddhism. The text alongside Kannon reveal the location of this print—Kinryūzan Sensō-ji Temple, Tokyo’s largest and oldest Buddhist Temple. The rectangular stamp on the top right corner reads “Bandō jūsan ban 坂東拾三番,” denoting Sensō-ji as the thirteenth location within the Bandō (former name of Kantō region) 33 Kannon Pilgrimage.1 The presence of a red shuin 朱印 in the middle, a seal stamp from the temple given to visitors or pilgrims,2 indicates this print is an ofuda 御札, a small paper slip representing the central icon of the temple that was sold or distributed to visitors.3

Pilgrimage

Before the Edo Period (1603-1867), a Buddhist pilgrimage was generally practiced by people with higher social status and the financial resources to travel. However, during the Edo period, there was an explosive trend to travel domestically with the development of several formalized pilgrimage routes, including those of 33 temples dedicated to Kannon.4 Pilgrimage not only showed religious devotion and accumulated karmic merit for the pilgrims, but was also a form of leisure. In a way, pilgrimage can be considered a forerunner of modern-day tourism. What is now known as the Japan 100 Kannon Pilgrimage is composed of three pilgrimage routes, each with around 33 stops and grouped in geographic proximity.5 The number 33 comes from the Lotus Sutra, which stated Kannon can become 33 different beings to save people, and each temple within the routes had a Kannon sculpture as their central icon. However, most temples did not publicly display this statue. To the pilgrims, knowing that they were in the presence of the deity at the site during the visit exceeded the importance of physically seeing the icon. Ofuda such as this work, therefore, acted as a souvenir to remind the devotees of their travel and perhaps as the only visual interaction with the deity’s figural form.6 As the stamps and the image of Kannon on these prints differed in each temple, these slips acted as a tangible form of sanctity accumulated by the pilgrims with each additional visit to a temple, and the spiritual power would be retained even after a pilgrim returned to their normal daily life.7

Substitute body of the deity

Ofuda can act as a direct physical substitute for the deity,8 making it not simply a representation of the actual deity or the temple’s sculpture but a potential bunshin 分身 (“alternate body”).9 The concept of bunshin is that the spirit is split from the original and relocated inside a new body. Therefore, ofuda, just like a relic, marks the very presence of the deity in an alternate material form, also containing the sacred protective power of the deity—in this case, Kannon—and allowing ofuda to act as a charm or talisman.10 The woodblock print form enabled the ofuda to be mass-produced, making ofuda accessible to a general group of worshippers, to whom larger Buddhist paintings or sculptures were hard to afford.11 Therefore, ofuda as a bunshin of Kannon acted in a manner similar to a relic, bringing the presence of Buddhist deities to practitioners in a tangible form, but as a more personal, affordable, and portable one.

Vivian Sanghee Han

History of Art, Cinema and Media Arts

Class of 2025

Cindy Yan

History of Art, Medicine Health and Society

Class of 2024

Annotated Bibliography

Kevin Bond. “Chapter 7: Buddhism on the Battlefield_ The Cult of the ‘Substitute Body’ Talisman in Imperial Japan.” In Material Culture and Asian Religions Text, Image, Object, ed. Benjamin Fleming and Richard Mann 120–29. London: Routledge, 2018.

The book discusses the different forms of materiality including but not limited to writing, amulets, talismans, and printings within different Asian religions, one being Buddhism. The chapter focuses on the practice of Japanese soldiers in imperial Japan (1890-1945) of taking Buddhist paper talismans to their battlefields for protection and luck. The author further explains how those talismans are the substitute bodies of the actual deity with elaboration on the concept of bunshin 分身(“alternate body”).

Fowler, Sherry. “Chapter 6: Connecting Kannon to Women Through Print .” In Women, Rites, and Ritual Objects in Premodern Japan, edited by Karen M Gehart, 221–66. Brill, 2018.

The book explores the complex relationships between gender politics, rituals, and materiality in premodern Japan. The rituals discussed in the book range from birth, household, and Buddhist, to death rituals. This chapter focuses on the examination of temples using printed texts and images to increase the participation of women in Buddhist pilgrimages. It touches upon pilgrimage as a popular practice around the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries and further explains the function of ofuda within the context of pilgrimage.

Kim, Jahyun. “Korean Single-Sheet Buddhist Woodblock Illustrated Prints Produced for Protection and Worship.” Religions, vol. 11, no. 12, Dec. 2020, p. 647. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120647.

This article examines the history, types, and function of single-sheet Buddhist woodblock prints. The author first recognizes the lack of systematic research done on this topic because of the brittle form of these prints that make them harder to be handed down as well as the lack of clear contextual information denoted on these objects. Still, a comprehensive study of this subject matter would be valuable in revealing social trends of the worship of Buddhism within the more ordinary public, since many iconographical subjects of these prints are temporal and shift with changes in social preferences. The paper also discusses two main functions of single-sheet woodblock prints for protection and worship, which are to serve as talismans and to act as a visual aid in place of larger and less accessible Buddhist paintings.

Salter, Rebecca. “Votive Slips and Exchange Slips.” Essay. In Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards, 94–107. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2006.

The most well-known and well-researched Japanese woodblock prints are Ukiyo-e depicting Kabuki actors and courtesans. The author tries to point out and highlight the wide variety of other Japanese woodblock prints including calendars, medicine prints, playing cards, and votive slips. This chapter clarifies the terminology difference between ema and fuda, and also further discusses the function and historical development of different kinds of fudas mainly focusing on senjafuda (votive slip) and kokanfuda (exchange slip). It also discusses how the creation and commission of fudas became highly popular during the Edo period.