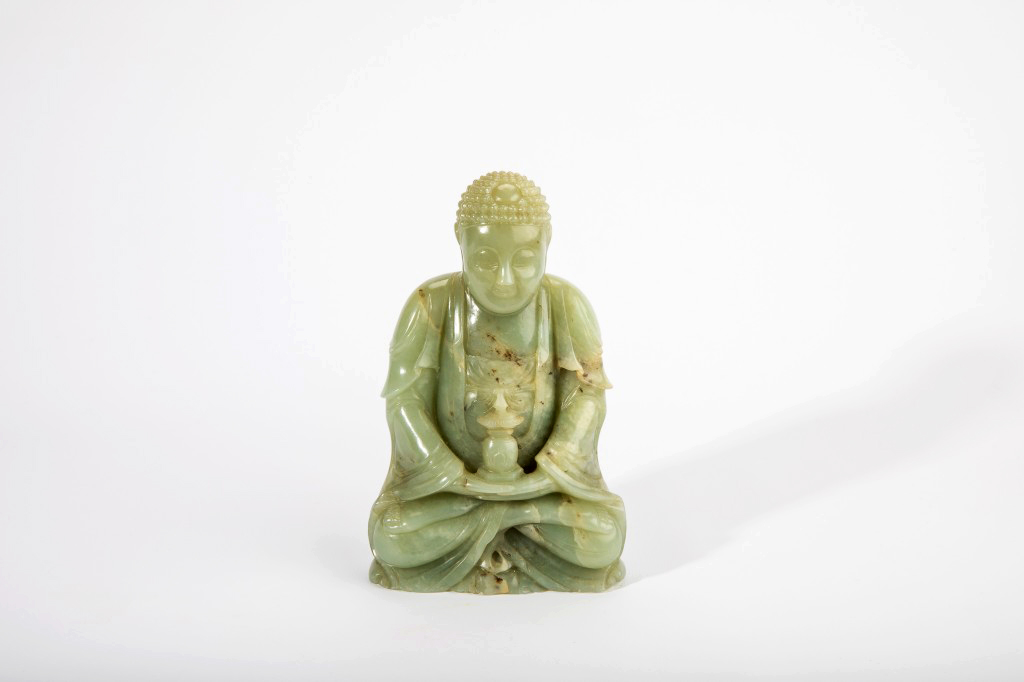

Seated Buddha in Dhyana Pose

Seated Buddha with reliquary, in dhyana pose

Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 CE)

Jade (rock)

8 x 4.25 x 1.75 in.

China

1999.241

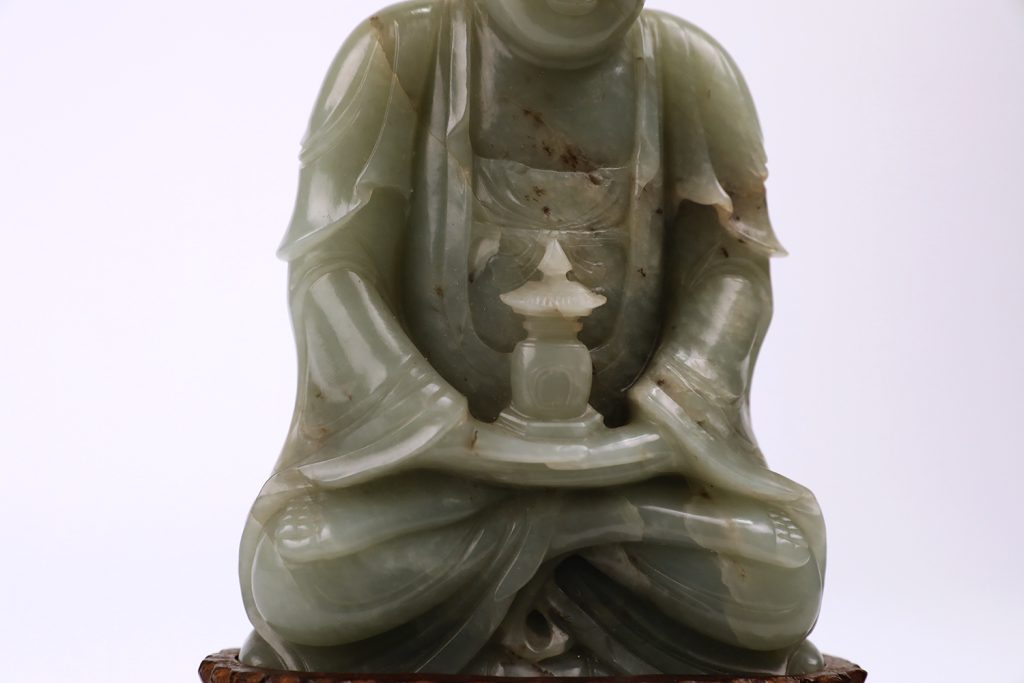

The Seated Buddha in Dhyana Pose reminds the viewer of Buddhist aspirations. The figure maintains the Buddha’s recognizable features with his cranial protuberance (ushnisha) and elongated earlobes that symbolize expanded wisdom and surrender of worldly desires, respectively. He displays a neutral, calm expression as he sits in a meditative state with his legs crossed and arms resting in his lap. The open, upward-facing palms demonstrate the dhyana mudra and hold a jar with an ornate lid.

In Buddhism, mudras, or hand gestures, serve as a means of communication. Each mudra represents specific events or qualities related to the Buddha that illustrate key principles of Buddhism. Followers believed the dhyana mudra allowed the Buddha to overcome worldly temptations to attain enlightenment through meditation.1

Buddhist relics often provide materiality to seemingly abstract concepts and can include fragments of the Buddha’s body, putting the owners in proximity to the sacred. Interestingly, this artifact entails the Buddha figure holding a relic—a proverbial genie outside of its bottle. The figure brings the “inner world” of the relic to the “outer world” of the viewer which might be attributed to considerations of introspection in Buddhism.2

From a frontal angle, the Buddha appears to have his eyes close as he meditates. However, if viewed from below, the figure seems to look upon his subject. Given that the object has indentations on the bottom with an accompanying wooden stand, it might be inferred that its maker desired the latter effect. However, its small size and ability to detach from the stand also suggest the encouragement of tactile interactions, as described below.

The jade object is dated to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), a time when the ascent of Confucianism imbued jade with an increased significance.3 Since Confucius (551-479 BCE) himself valued jade for its association with virtues such as kindness and wisdom, the mineral represented a connection to Confucius and his teachings. Jade was also highly valued for its sensory appeal.4 The smooth, polished jade allowed for engravings and textures to stand out, while the warm colors comforted the eyes.

While the figure maintains traditional iconography with the Buddha’s likeness and mudra gesture, its jade material, ornate wooden stand, and pagoda-like relic also signify value and notability.

The statue’s material and the Buddha’s appearance give us reason to believe that the figure might have served as a meditation tool, looking upon its viewer as a reminder to discipline his mind. By making the object out of jade, its makers could have been imbuing the figure with additional meaning associated with jade such as making a connection between meditation and jade’s symbolism of wisdom. The flower-like ridges tracing the bottom of the stand and the regular light streaks around the dark wood base demonstrate the attention to detail. With the removable stand, the object’s owners could have held the statue, utilizing its smooth, cool tactile qualities to quiet the mind.

For Buddhist practitioners, qualities such as the jade material and the figure’s ushnisha provided a physical representation of inner virtues such as wisdom and enlightenment, guiding them in attaining these very virtues through meditation. As the Buddha figure makes the inner world of a relic visible, the object itself illustrates qualities of the inner, enlightened mind.

Qiuchen Li

Biology

Class of 2023

Sahanya Bhaktaram

History of Art; Communication Studies

Class of 2023

Annotated Bibliography

Ghori, Ahmer K, and Kevin C Chung. “Interpretation of Hand Signs in Buddhist Art.” The Journal of Hand Surgery., no. 6 (2007): 918-922. https://doi.org/info:doi/.

This article provides an entry-level understanding of mudras and the communicative role hand gestures play in Buddhism. The authors outline the meaning behind six mudras, the elements that correspond to each finger, and the difference in meaning between one’s right and left hand. In explaining the mudras, the article provides a connection between the dhyana mudra and meditation.

Purton, Campbell. “Buddhist, Meditation, and ‘the Inner World.” Religious Studies 53, no. 2 (2017): 183-197. doi:10.1017/S003441251600007X.

This article describes Buddhist meditation as connecting oneself to one’s “inner world,” categorized by one’s thoughts. Purton grapples with the labeling one’s thoughts and feelings as the inner and whether introspection is an outdated way of considering mediation.

Wu, Yulian “Chimes of Empire: The Construction of Jade Instruments and Territory in Eighteenth Century China” Late Imperial China, vol. 40, issue 1 (2019): 43-85. doi:10.1353/late.2019.0002.

This article details the historical context of the Qing dynasty, focusing specifically on the Qing court’s occupation of Xinjiang. Discussing the military and economic triumphs of the time period, the author explores the relevance of Confucianism and the associated significance of jade. Wu explains the importance of chimes (the ritual instrument of confucianism) and recounts the significance of the material from which chimes were constructed in enforcing the agenda of the imperial court.

Steuber, Jason “Politics and Art in China, the Duanfang collection.” Apollo Magazine, vol. 162 issue 525 (2005)

This article examines the history, types, and function of single-sheet Buddhist woodblock prints. The author first recognizes the lack of systematic research done on this topic because of the brittle form of these prints that make them harder to be handed down as well as the lack of clear contextual information denoted on these objects. Still, a comprehensive study of this subject matter would be valuable in revealing social trends of the worship of Buddhism within the more ordinary public, since many iconographical subjects of these prints are temporal and shift with changes in social preferences. The paper also discusses two main functions of single-sheet woodblock prints for protection and worship, which are to serve as talismans and to act as a visual aid in place of larger and less accessible Buddhist paintings.