Nashville Sit-ins

During their first meeting in February 1957, Martin Luther King, Jr. recognized James Lawson’s special understanding of non-violent direct action and its potential as an instrument for social change. King encouraged Lawson to move to the South to work on the campaigns for desegregation, beginning in Nashville. There, Lawson led training on non-violent techniques to desegregate lunch counters. For his role in these “Nashville Sit-Ins” Lawson was expelled from Vanderbilt University and arrested for “conspiring to violate the state’s trade and commerce law.” His expulsion and arrest would spark protests and the resignations of Vanderbilt faculty members and accelerate the successful desegregation of Nashville lunch counters.

![[James Lawson Teaching Non-violence]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/MSS0626-B2Memphis-Lawson-non-violent_protest_class-Ernest_Withers150-1500-1024x831.jpg)

[James Lawson Teaching Non-violence]

Reproduction of a photograph, c. February 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

![[Our Statement of Purpose]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/2R-NashSitIns-30x39-150-1500-795x1024.jpg)

[Our Statement of Purpose]

Nashville Non-Violent Movement, c. 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

![[James Lawson Arrested at First Baptist Church]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/MSS0626-Lawson_Papers-arrested_at_1st_Baptist_Church-Nashville-March_5_1960-02-150-1500-1024x830.jpg)

[James Lawson Arrested at First Baptist Church]

Photograph, March 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collection

![[James Lawson Statement on His Expulsion from Vanderbilt University]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/Rough-draft-statement-on-VU-Expulsion-Box-21-folder-29-150-1500-784x1024.jpg)

[James Lawson Statement on His Expulsion from Vanderbilt University]

Typed draft, c. June 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collection

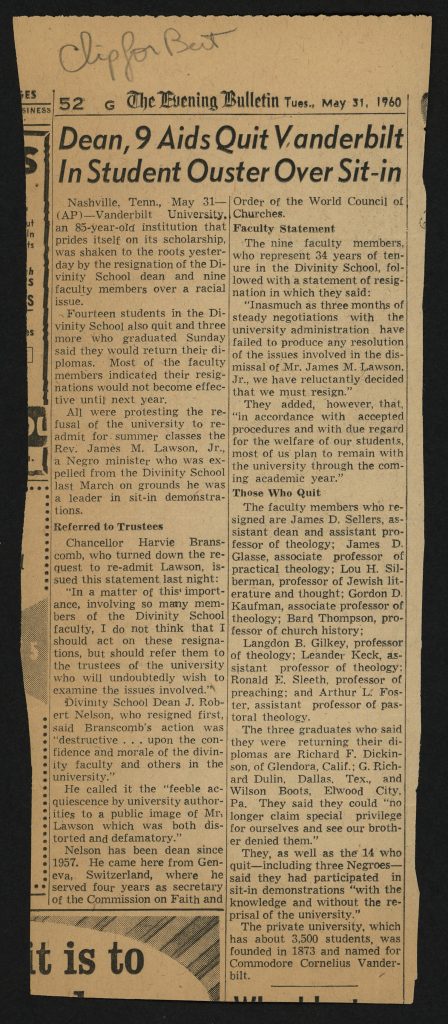

“Dean, 9 Aids Quit Vanderbilt in Student Ouster over Sit-In”

The Evening Bulletin

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 31, 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collection

![[Letter to James M. Lawson]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/Letter-Septima-Clark-1960-Box-21-folder-9-150-1500-781x1024.jpg)

[Letter to James M. Lawson]

Septima Clark

Monteagle, Tennessee, March 22, 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collection

![[Letter to James M. Lawson]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/Hate-letter-Box-21-folder-20-03-150-1500-1024x849.jpg)

[Letter to James M. Lawson]

Anonymous author

June 9, 1960

James M. Lawson, Jr. Papers

Vanderbilt University Special Collection

Note from Kashif Andrew Graham, co-curator: The language used in this letter may be painful for some viewers. My decision to include this document reflects both my identity as a Black queer male, and my personal value of open conversation. The letter, kept in Lawson’s collection for over 50 years, speaks to the courage of his nonviolent mission in the presence of a violent spirituality. I believe that historical trauma can only be remedied by an honest reckoning with the past and have included the letter for this reason.

![[James Lawson Student Identification Card]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/VU-ID-Box-3-folder-1-01-150-1500-721x1024.jpg)

![[James Lawson Student Identification Card]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/VU-ID-Box-3-folder-1-02-150-1500-1024x720.jpg)

![[Letter to James M. Lawson]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/Hate-letter-Box-21-folder-20-01-150-1500-760x1024.jpg)

![[Letter to James M. Lawson]](https://exhibitions.library.vanderbilt.edu/lawson/wp-content/uploads/sites/60/2022/10/Hate-letter-Box-21-folder-20-02-150-1500-769x1024.jpg)