Prescribing Community

Godey’s Lady’s Book 1868: Building Community through Prescriptive Literature

1865: a people divided. 1868: a people rebuilding and reuniting their nation.

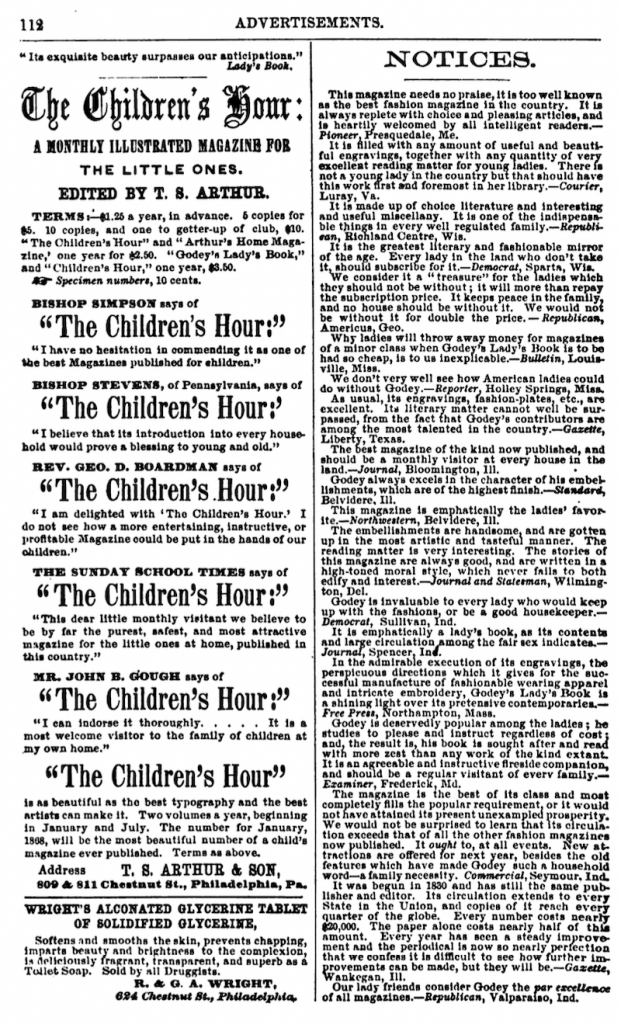

When Louis Antoine Godey began publishing the Lady’s Book in 1830, he hoped to create a resource on all feminine interests: fashion, literature, family management, etc. In 1837, Godey hired Sarah Josepha Hale as the editor. Hale, a daughter of an American Revolutionary War officer, injected an almost devout sense of national pride in the Lady’s Book by exclusively publishing original, American content and promoting American sentiments. Although the Lady’s Book reached its peak in the 1860s, amassing a subscribership of over 150,000, Hale and Godey soon had to reconcile the effects of the Civil War on the periodical industry and help reunify America.

How could Hale and Godey unite readers and rescue the Lady’s Book from financial ruin in the process? They did so by fostering a collaborative culture through prescriptive literature on every aspect of domestic management.

Everybody Skates

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Monthly Periodical published 1830-1878

Philadelphia, PA

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

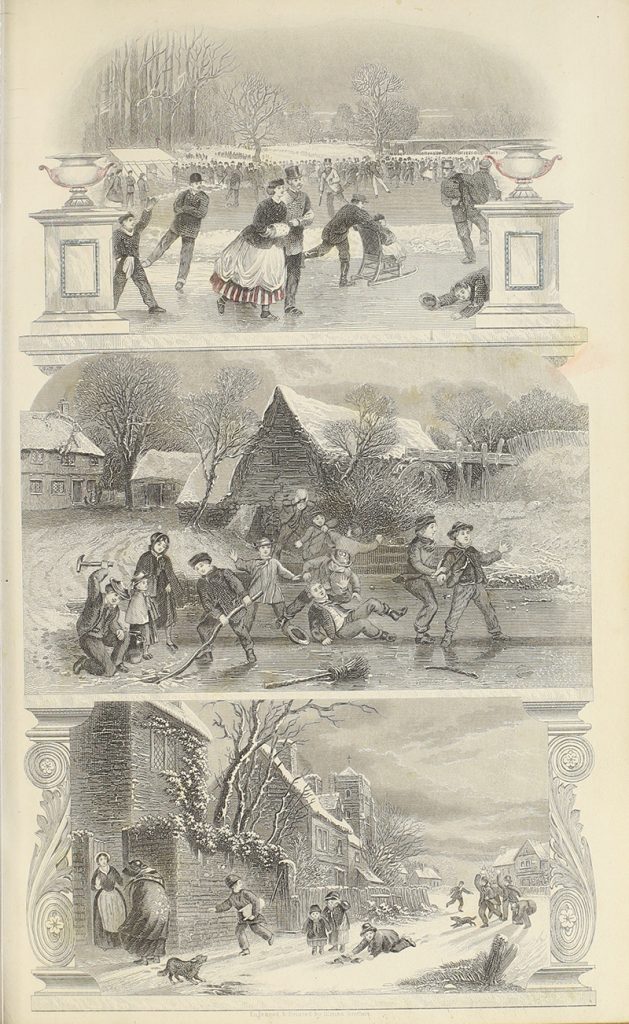

The January 1868 issue marks the 451st publication of Godey’s Lady’s Book. Like previous title pages, this New Year’s edition depicts popular leisure activities. Unlike others, this title page lacks the magazine’s title, editor, and owner printed in its center. This emphasis on leisure on the title page underscores how the Lady’s Book, and literature overall, helped facilitate imaginative escape for its readers in an era marked by great urban development.

When describing the title page, Sarah Hale writes, “Our title-page, on steel, represents three popular winter amusements—skating, sledding, and snow-balling. The latter have always been favorite occupations with boys, and, until the last few years, the first was almost confined to them; but now everybody skates, and ladies are especially renowned for their grace and agility.” Hale identifies this January edition as “a model one,” and her message on opportunity, equity, and exceeding expectations suggests why. This sentiment carries throughout the year’s issues, ranging from discussions on access to higher education and woman’s suffrage.

A Ray of Peace, Intelligence, and Happiness

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Monthly Periodical published 1830-1878

Philadelphia, PA

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

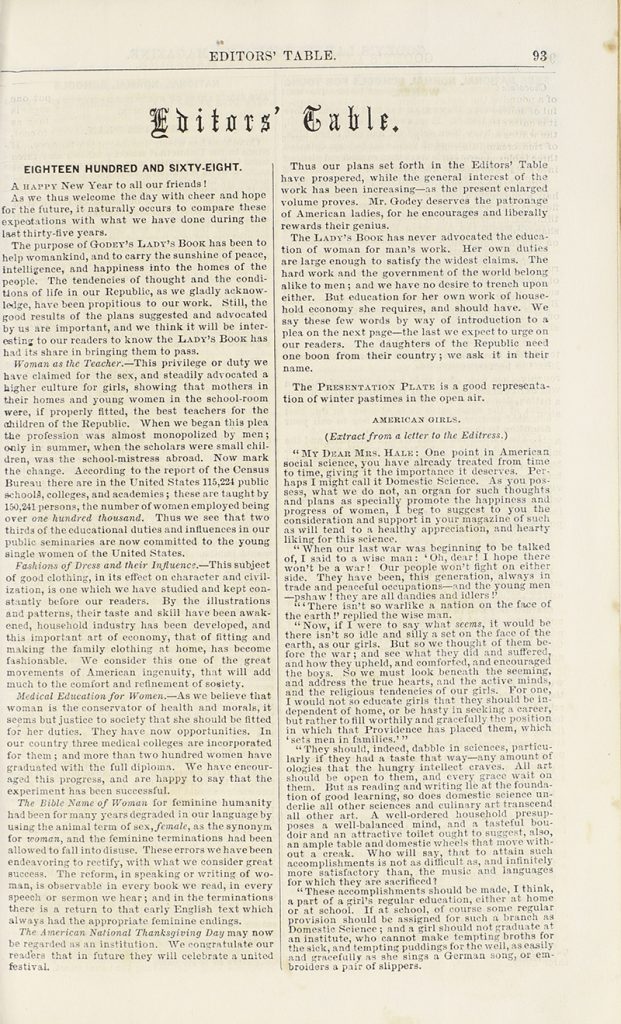

In her January editor’s address, Sarah Hale outlined her ambitions for the Lady’s Book. Hale hoped for the publication to “carry the sunshine of peace, intelligence, and happiness” into American’s homes by promoting women’s education, high culture, and national holidays and sentiments.

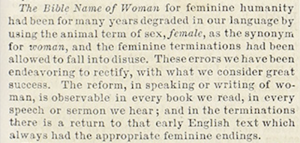

Under the subtitle “The Bible Name of Woman,” Hale highlighted her hopes of uplifting standards of femininity by challenging linguistic traditions. Hale writes, “Feminine humanity had been for many years degraded in our language by using the animal term for sex, female, as the synonym for woman.” Hale linguistically distanced “women” from animals, epitomizing her hopes of distinguishing her readers from the uncouth while also reinforcing nineteenth century domestic ideals about women’s gentility.

Rebellious Praise

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Monthly Periodical published 1830-1878

Philadelphia, PA

Vanderbilt University Special Collections and University of Michigan

Despite references within the Lady’s Book to subscribers in Canada, London, and Cuba, the specific geographical circulation of the Lady’s Book in 1868 is uncertain due to a lack of records. However, the responses of various newspapers across the nation to the Lady’s Book help approximate the extent of its circulation and following.

Base map source: United States Census Office. 9Th Census, 1. & Walker, F. A. (1874) Statistical atlas of the United States based on the results of the ninth censuswith contributions from many eminent men of science and several departments of the government. [New York J. Bien, lith] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/05019329/.

The distribution of reviews underscores the effect of the Civil War on the Lady’s Book. As it was published out of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the southern blockade eliminated a vast proportion of the Lady’s Book readership. The few scattered volumes that penetrated southern lines were treasured by Confederate women. This destabilizing effect was exactly what Hale had anticipated, warned of, and even opposed during previous years’ editions. As L.A. Godey prohibited the mention of divisive politics, Hale embedded her political opinions and patriotism in her selections of articles, poetry and prose, intentionally but covertly attempting to unify the nation.

Linguistic Bloom

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Monthly Periodical published 1830-1878

Philadelphia, PA

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

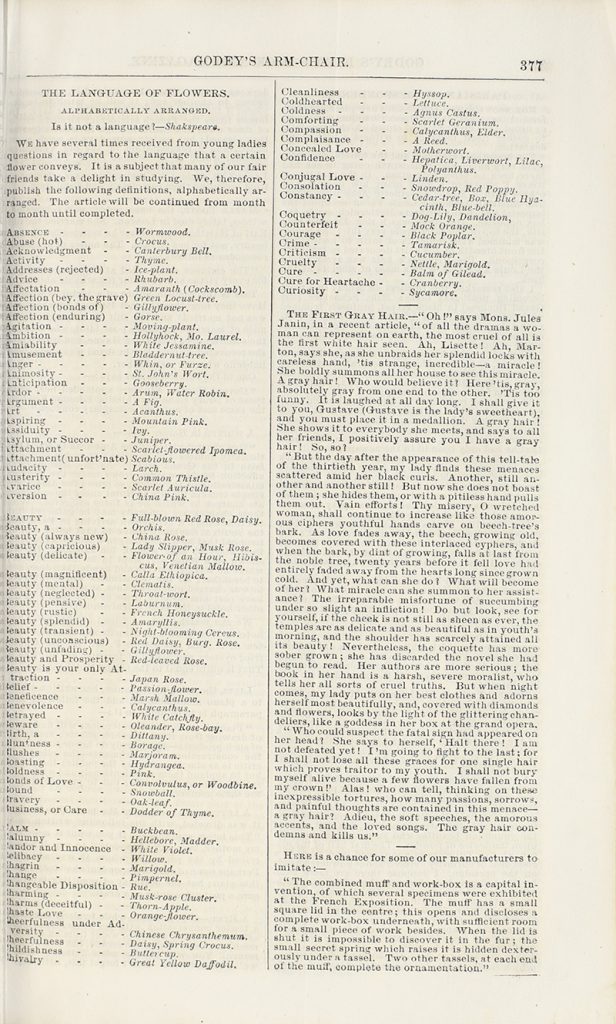

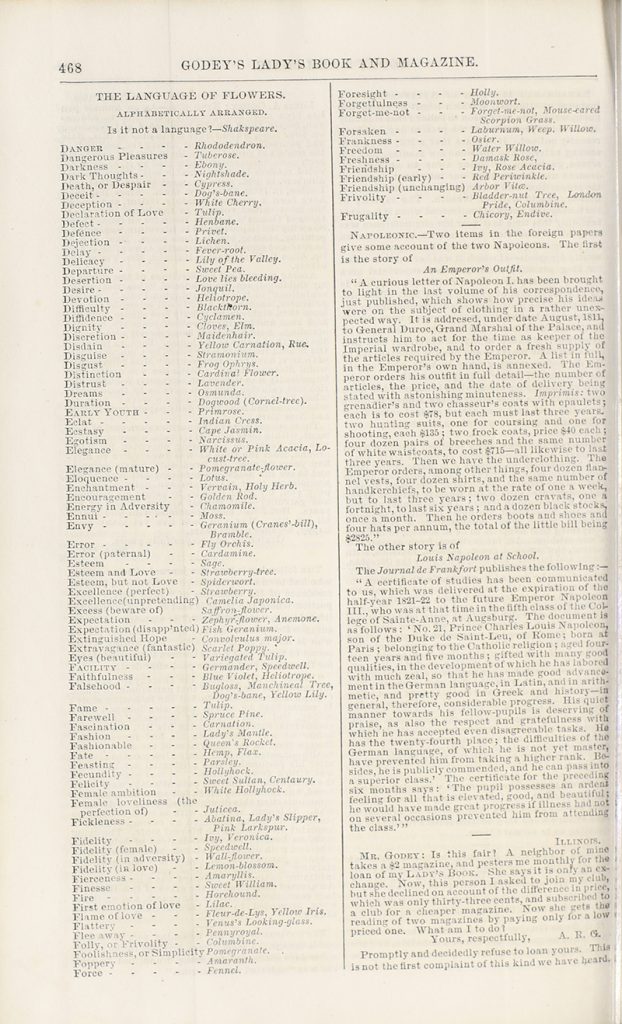

From April to September, the Lady’s Book featured a “Language of Flowers,” relating physical traits and emotions to particular flowers. The lily of the valley represents one of the three types of happiness and the gillyflower signifies one of the thirteen types of beauty. In the April issue, Sarah Hale writes of the many requests she’d received for this language, showcasing how subscribers actively shaped the contents of the Lady’s Book.

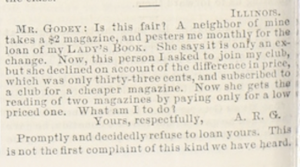

Hale also published stories from subscribers showcasing their loyalty to the Lady’s Book by refusing frequent requests to loan their copies to neighbors. Hale addressed this topic in the February issue. She writes, “Calculating that only ten persons read each number of our magazine—and it is often twenty—then is our magazine read by one million one hundred thousand persons monthly. Now, if only a few of these borrowers would subscribe, imagine what a subscription list we would have.”

Contributed Cures for Drunkenness

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Monthly Periodical published 1830-1878

Philadelphia, PA

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

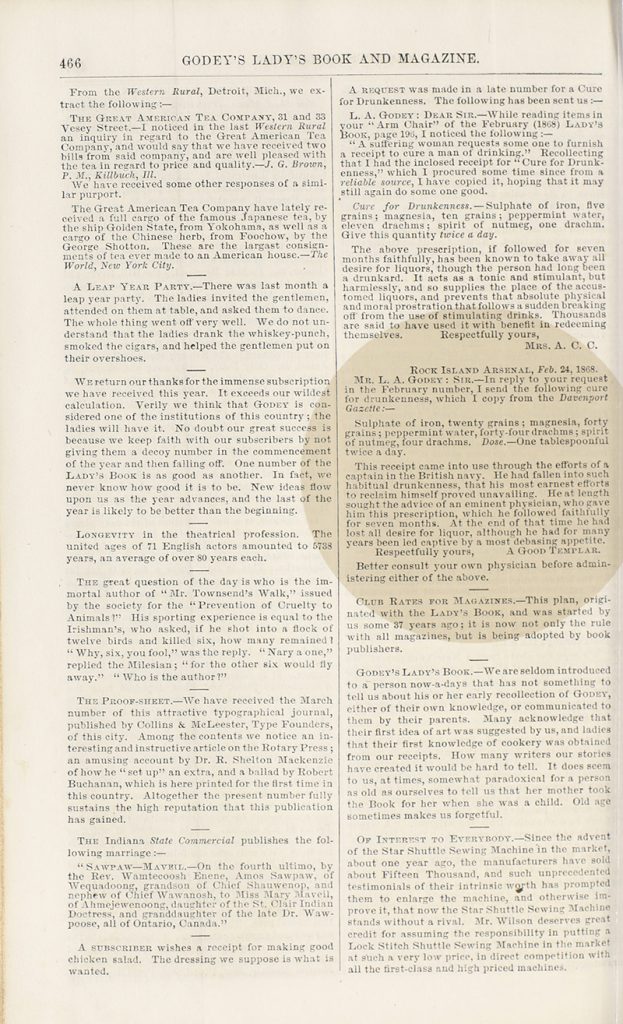

Every issue of the Lady’s Book included professional medical advice in a “Hints about Health” section. Sarah Hale also published receipts contributed by readers, often in response to requests made by other readers. Readers contributed two cures for drunkenness in the June 1868 issue. One contributor writes, “While reading… the February (1868) Lady’s Book, page 196, I noticed the following: ‘A suffering woman requests some one to furnish a receipt to cure a man of drinking.’” Both prescriptions involve iron, magnesium, and nutmeg, suggesting a common source for the two remedies.

The issue contains one final reference to these cures. Hale writes, “Miss M.—The remedy for drunkenness you send would kill the patient. That would certainly cure the complaint.” While the published receipts showcase readers’ ability to share their knowledge through the Lady’s Book, this brief address reveals the way Hale utilized such replies to interact with her community.

Blueprints for America

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879)

Godey’s Lady’s Book

Monthly Periodical published 1830-1878

Philadelphia, PA

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

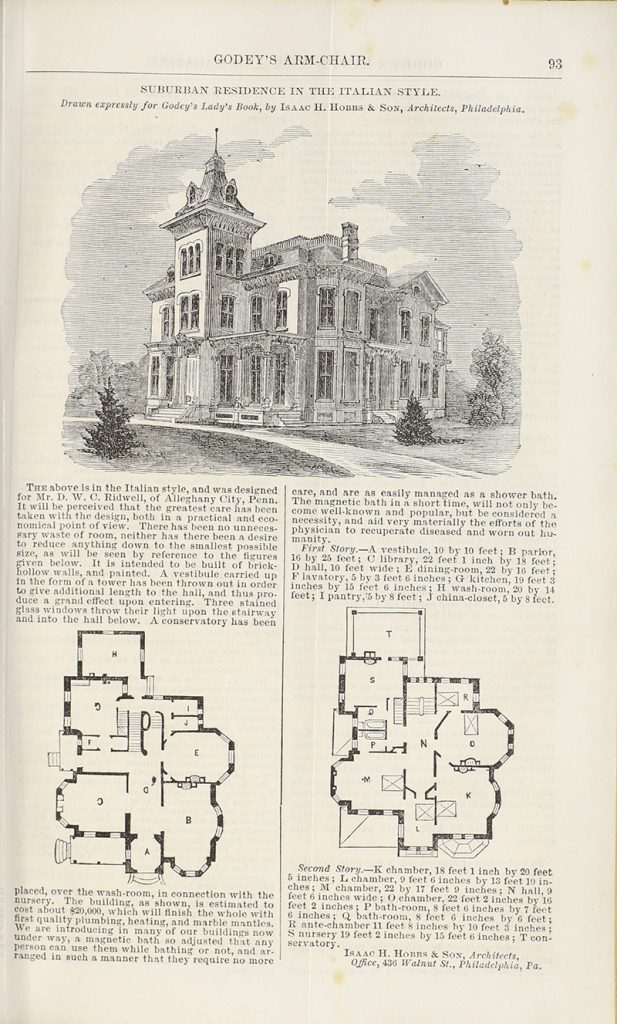

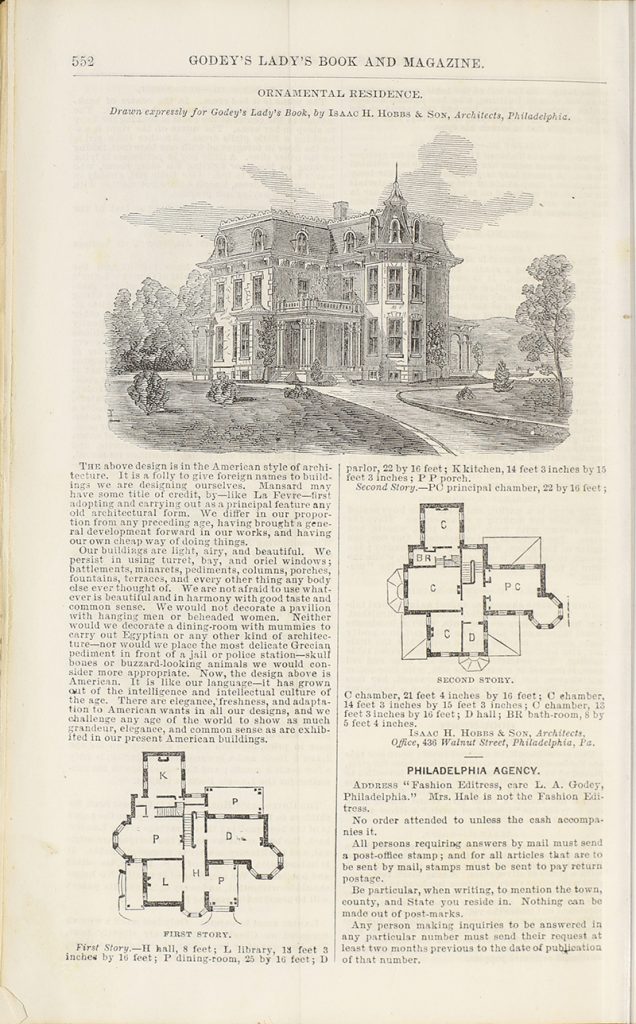

Not only did Sarah Hale utilize the Lady’s Book to reinforce nineteenth century standards for public appearance and domestic management, but she also showcased residences fit for a “lady.” Beginning in 1846, Hale featured sketches and blueprints for homes, often modeled after European architecture, in every issue. Throughout the years, Hale printed over 450 designs, allowing middle class readers to appreciate an art which was long considered a pastime for the wealthy.

Hale describes this “Ornamental Residence” as in the “American style.” When distinguishing this style from European, Hale addresses potential European influences but writes, “It is like our language—it has grown out of the intelligence and intellectual culture of the age.” This idea encapsulates the heart of the Lady’s Book: curating stories, receipts, and fashions that, despite potentially deriving from foreign cultures, promote America’s identity, unifying readers under this culture collectively constructed, brick by brick, by its citizens.