Tending to Popular Thought

Tending to Popular Thought: What People Read and Why

The curatorial fellows in spring 2020—Quiyang Cui, Emma Claire Geitner, Gabrielle Rodriguez, and Jessica Prus—found working closely with period books captivating. They framed their exhibit around popular literature—how it mirrors popular culture, how books are produced and why they remain popular or become obscure.

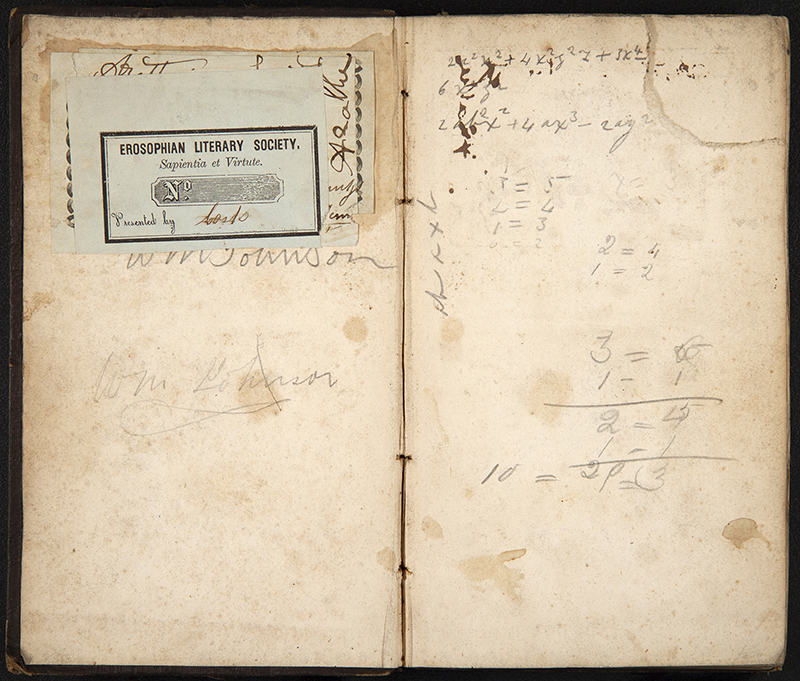

Martin Faber, the Story of a Criminal: And Other Tales

Book, 1837

William Gilmore Simms

University of Nashville Collection

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

Martin Faber: the Story of a Criminal (1837) was part of the University of Nashville’s Erosophian Society members-only library. William Gilmore Simms’ friend Edgar Allen Poe thought his fellow writer a genius of “no common order.” A hugely popular early psychological thriller, Martin Faber examines the psychology of murderers through a murderer’s own narration.

Scholastic Literature

Book, 1870

Complied by Calvin Robinson Darnall, President of Lewisburg Institute

Nashville, TN: Southern Methodist Publishing House, 1870

University of Nashville Collection

Vanderbilt University Special Collections

Calvin Darnall drew on his students’ final “speeches, compositions, and literary addresses” for three years from 1876-1869 to compile Scholastic Literature. These male and female college-level graduates spoke and wrote on topics like “Appearances Deceive,” “Personal Beauty, Wealth and Talent,” and “Electricity” for popular, public graduations. Darnall hoped his book would show his students’ “talent and ability” in the postwar South. Classes averaged 170 pupils per year.

A New Herball: wherin are conteyned the names of herbes in Greke, Latin, Englysh, Duch, Frenche, and in the potecaries and herbaries Latin…

Book, 1551

William Turner

London, printed by Steven Mierdman

History of Medicine Collection

Eskind Biomedical Library

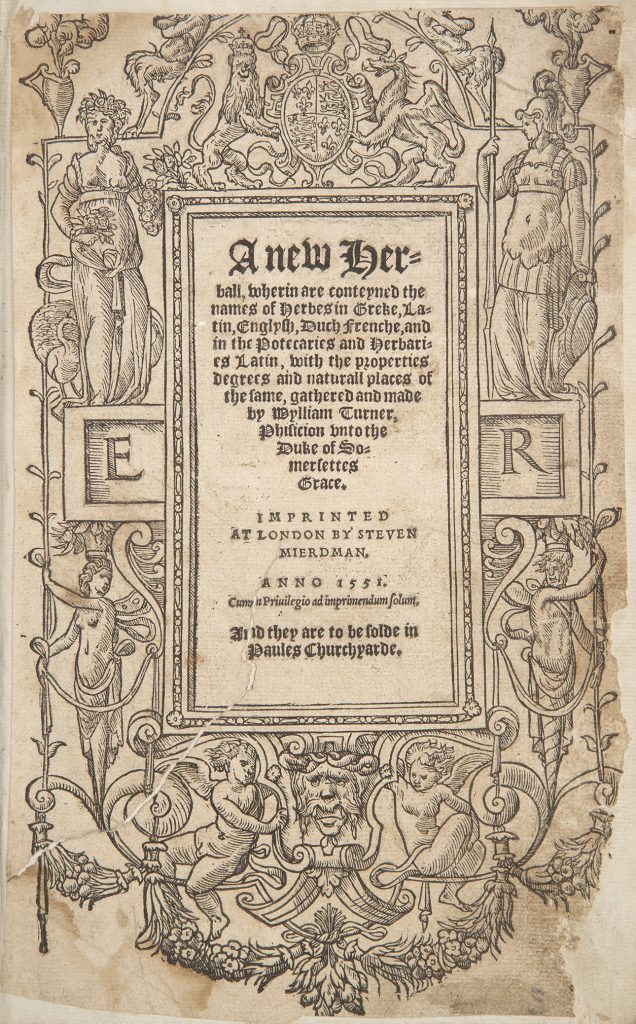

William Turner’s 1551 A New Herball, the culmination of years of education and exile abroad, brought the Latinate and Greek botanical traditions to Turner’s English audience. The text, written in the English vernacular, was a self-conscious popularization of knowledge previously reserved for those able to grace the halls of Cambridge and Oxford, a privileged few. Although Turner himself was a Cambridge graduate, a generous patron made his education and subsequent writings possible. Turner worked to disseminate practical information pertaining to local flora and fauna to a readership that did not know Latin. He wrote with the apothecaries of England in mind, his use of vernacular supported by his Calvinist faith.

A New Herball illustrates Turner’s medical training and practice—he intended it to be used in apothecaries—and is the product of his travels, which this title page makes explicit: “A new Herball, wherin are conteyned the names of herbes in Greke, Latin, Englysh, Duch, Frenche.” Turner dedicated this Herbal to his patron, Edward Seymour, the first Duke of Somerset. However, the page does not bear the duke’s heraldry, but rather that of his Tudor nephew, King Edward VI, a fellow Protestant and of whom the duke was Lord Protector. The monarch’s initials: “E.R” (Edward Rex) are also included on the title page.

Title page

William Turner (1508-1568), born in Morpeth, Northumberland, spent much of his life and career traveling across Europe, preaching the Reformation and studying medicine. Between 1526-33, Turner received both a BA and a MA from Cambridge University’s Pembroke Hall. Following his graduation, Turner began to preach the Reformed doctrine until his arrest and exile c.1540, after which he fled to Italy where he studied medicine at either Ferrara or Bologna and earned his MD in 1542. Turner continued to ardently support the Reformation throughout his life. His religious stance likely introduced him to the Dutch Protestant Steven Mierdman, the prolific publisher of this herbal.

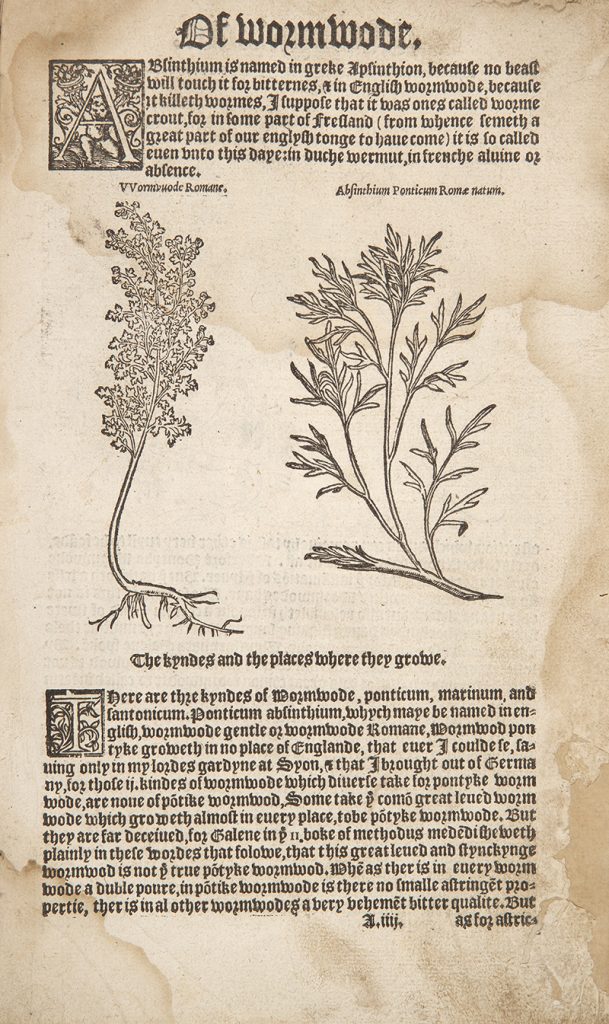

Wormwood

William Turner followed a format used in other herbals: each plant is named in Greek, English, Dutch, and French. Turner lists of the three types of wormwood he names: “ponticum, marinum, and santonicum,” this page only discusses “ponticum absinthinum” or “Roman Wormwood,” which, Turner asserts, is not native to England. He notes that wormwood grows in his patron’s garden at the Duke of Somerset, at Syon House, London, only because Turner brought the plant with him from Germany. Turner also cites Galen’s (the great Greek physician and medical author) Methodus Medendi to substantiate this claim, illustrating the influence that ancient sources maintained into the early modern period.

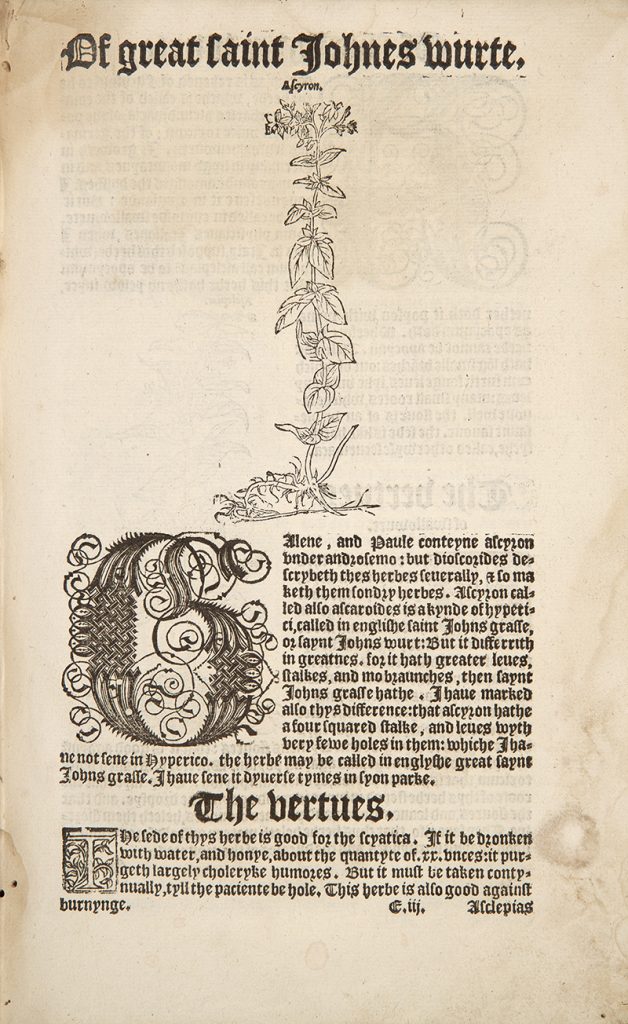

Of Great Saint John’s Wort

Saint John’s Wort was widely used by apothecaries and others. By situating the image prominently, Turner helps his readers easily identify the plant. Found throughout Europe and discussed by Galen, Paul of Aegina, and Dioscorides, Turner wrote that Saint John’s Wort could purge one of choleric humors (a nod to Hippocrates’ humorism) if taken continually with water and honey and was “also good against burnyinge.”