IV. Society

IV. Society

From the beginning, print artists have gravitated toward social themes. Printmaking, after all, was the first visual medium that enabled mass distribution of images in society. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, genre scenes (depictions of everyday life) were widely disseminated in print form. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, prints offered popular social satire as well as commentary on current political events. By the nineteenth century, especially with the rise of lithography and wood engraving, prints became an integral part of journalism. Through this inherently “social” medium, artists have offered trenchant or entertaining observations on social and political conditions, many of which have become canonical works of art. It is not an overstatement to say that the focus on society is a genre in its own right and that many a print artist has functioned as a social activist.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543)

The Preacher (ca. 1524), from The Dance of Death (1538)

Woodcut

2 9/16 × 1 7/8 (6.5 × 4.8 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Hans Holbein the Younger, renowned court painter of Henry VIII, was also a major print artist, especially accomplished in small format woodcuts. He designed The Preacher for The Dance of Death, a humorous pamphlet that satirizes hierarchical society from top to bottom, from pope to pauper. Personified as a bare skeleton in each woodcut, Death snatches away a member of society, showing the vanity of social status and the futility of human aspirations. In this sardonic example, Death wears a clerical stole and mocks a priest who is sermonizing on the transcendent quest for salvation. The priest may be versed in theology and firmly believe in eternal life, but only Death truly knows what awaits us in the afterlife.

The text, which Holbein did not select, implies that the priest is corrupt and deceitful: “Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil; that put darkness for light, and light for darkness; that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter.” The Protestant Reformation, which had just recently begun, fomented high levels of anti-clericalism.

Courtney Rehkamp

PhD student in German, Russian & East European Studies

Hart 2775: History of Prints

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Foister, Susan. Holbein and England. New Haven: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale University Press, 2004

Holbein, Hans. The Dance of Death, ed. Ulinka Rublack. London: Penguin, 2017

Price, David H. “Hans Holbein the Younger and Reformation Bible Production.” Church History 86 (2017): 998-1040

Zijlma, Robert. Ambrosius Holbein to Hans Holbein the Younger. In Hollstein’s German Engravings, Etchings and Woodcuts 1470-1700, ed. Tilman Falk. Vols. 14, 14A, and 14B. Roosendaal: Koninklijke van Poll, 1988

Pieter Bruegel (ca. 1526-1569)

Justice (1559)

Engraving

8 3/4 × 11 1/2 (22.2 × 28.3 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Pieter Bruegel did not exaggerate the harshness of criminal justice in sixteenth-century Europe. By incorporating grotesque images of men hanging by their limbs, being whipped on a post, and tortured on a rack, Bruegel censures the wicked forms of judicial punishment ravaging the era. Standing on a pedestal in the foreground center, Justice is personified as a woman with a blindfold and a sword, presiding over the horrific scene. Usually, Justice is blindfolded as a symbol of impartiality. In this image, however, Justice appears blind to the atrocities being committed in her name. Although the message is ultimately ambiguous, the graphic representation of such inhumanity may be a call to reform.

Bruegel, a renowned painter, arranged for the professional engraver Philipp Galle to make this work after his detailed drawing (modello).

Won Jun Seok

Psychology

Class of 2023

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Lavalleye, Jacques. Bruegel and Lucas van Leyden: Complete Engravings, Etchings, and Woodcuts. New York: Abrams, 1967

Stechow, Wolfgang. Pieter Bruegel the Elder. New York: Abrams, 1970

Wenceslaus Hollar (1607-1677)

Woman with Pearl Necklace, plate 11 from Ornatus Muliebris Anglicanus (English Women’s Clothing) (1644)

Etching

5 1/4 x 3 (13.3 × 7.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Despite blindness in one eye, Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar produced an enormous oeuvre of over two thousand five hundred prints with keen observations of seventeenth-century European life. Working in the service of Thomas Howard, the 21st Earl of Arundel, Hollar amassed an encyclopedic knowledge of clothing and accessories. Ornatus Muliebris Anglicanus, a set of twenty-six plates, documents a broad spectrum of fashion ranging from that of the humble countrywoman to the lady-in-waiting at court. Our example, Woman with Pearl Necklace, illustrates the ornate, extravagant dress worn by English nobles. In addition to her necklace, the lady sports two-strand pearl bracelets on both arms, wide lace cuffs on the sleeves, and a large bow at the neckline of her floor length gown. Because the etchings were based on Arundel’s accounts of the clothing at court, the prints function as a valuable visual source for fashion historians.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Griffiths, Antony, and Gabriela Kesnerová. Wenceslaus Hollar: Prints and Drawings from the Collections of the National Gallery, Prague, and the British Museum, London. London: British Museum Publications, 1983

Merling, Mitchell, and Colleen Yarger. Hollar’s Encyclopedic Eye: Prints from the Frank Raysor Collection. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2019

Pennington, Richard. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Etched Work of Wenceslaus Hollar, 1607-1677. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

Gin Lane (1751)

Etching and engraving

15 1/4 × 12 3/4 (38.7 × 32.4 cm)

Collection of Jack May

William Hogarth is one of the most acclaimed satirists in the history of art. Like the eighteenth-century moralistic novel, his prints are so rich in detail that it is necessary to spend time “reading” them. Moreover, many of his projects are series of engravings that portray a narrative, often with a tragic or sentimental end. Like the novelists, Hogarth explores societal malaises such as criminality, alcohol abuse, prostitution, and elite entitlement.

Hogarth pairs Gin Lane with Beer Street to contrast a utopia of wholesome English beer drinking with the evils of consuming imported gin. On the left side of Gin Lane, residents sell the tools of their trades to a pawn broker while a man fights with a dog for scraps of food. On the right, addicts riot over cheap gin while forcing the drink down the throats of others. In the front, we see malnourishment and neglect. In the back, a woman in a coffin, an impaled baby, and a suicidal barber represent the horrific decay of society. Amidst the collapsing buildings and suffering people, only a distillery, a pawn broker, and an undertaker prosper. Hogarth produced this work as part of a reform effort—Parliament responded with the Gin Act of 1751, which limited the import of the destructive beverage.

Christopher Elliott

Vocal Music Education

Class of 2021

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

O’Connell, Sheila. “Hogarth, William.” Grove Dictionary of Art

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth. 3 vols. Cambridge: Lutterworth, 1992

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

Beer Street (1751)

Etching and engraving

15 1/4 × 12 3/4 (38.7 × 32.4 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Hogarth’s name is synonymous with visual social satire. One of his best-known works is Beer Street, a boisterous promotion of the “British” middle class as hard-working and fun-loving. The conviviality of the beer-drinking artisans and laborers, who are celebrating the King’s birthday, links industry, virtue, and patriotism to prosperity and the enjoyment of life. The steeple of London’s landmark St. Martin-in-the-Fields is visible in the background, where a flag is flying to commemorate George II’s birthday. Hogarth designed Beer Street as a pendent to the dystopic Gin Lane, an engraving that portrays a London slum where the residents have succumbed to gin addiction.

Sophia Moak

Mechanical Engineering

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Einberg, Elizabeth. Manners and Morals: Hogarth and British Painting, 1700-1760. London: Tate, 1987

Wind, Barry. “Gin Lane and Beer Street: A Fresh Draught.” In Hogarth in Context: Ten Essays and a Bibliography, ed. Joachim Möller, 130-42. Marburg: Jonas, 1996

Francisco Goya (1746-1828)

Dios la perdone: Y era su madre, plate 16 from Los Caprichos (1799)

Engraving and aquatint

7 3/4 × 5 7/8 (19.7 × 15 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Los Caprichos is a set of eighty prints (engravings, etchings, and aquatints) that Francisco Goya created as an experiment in social criticism. The series portrays the follies and weaknesses he perceived in contemporary Spanish society, from superstition, ignorance, cruelty, greed (and wealth inequality), to prostitution. The artist hoped to illuminate moral values and ameliorate injustices by engaging the viewer’s imagination.

In this image, Goya depicts a maja, a young woman of lower-class origins dressed in traditional Spanish costume. Majas, who in some cases were prostitutes, had become a recurring subject throughout Goya’s works across various media. This maja turns her back on a crippled, elderly beggar woman bowing her head and clutching her rosary beads in prayerful desperation. The image has the following caption: “God forgive her. It was her mother.” Goya highlights the cruel vanity that, in her finery and comfort, the young woman rejects her own flesh and blood, the source of her humanity.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Hagen, Rose-Marie, and Ranier Hagen. Goya. Cologne: Taschen, 2016

Tomlinson, Janis. Goya: Images of Women. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002

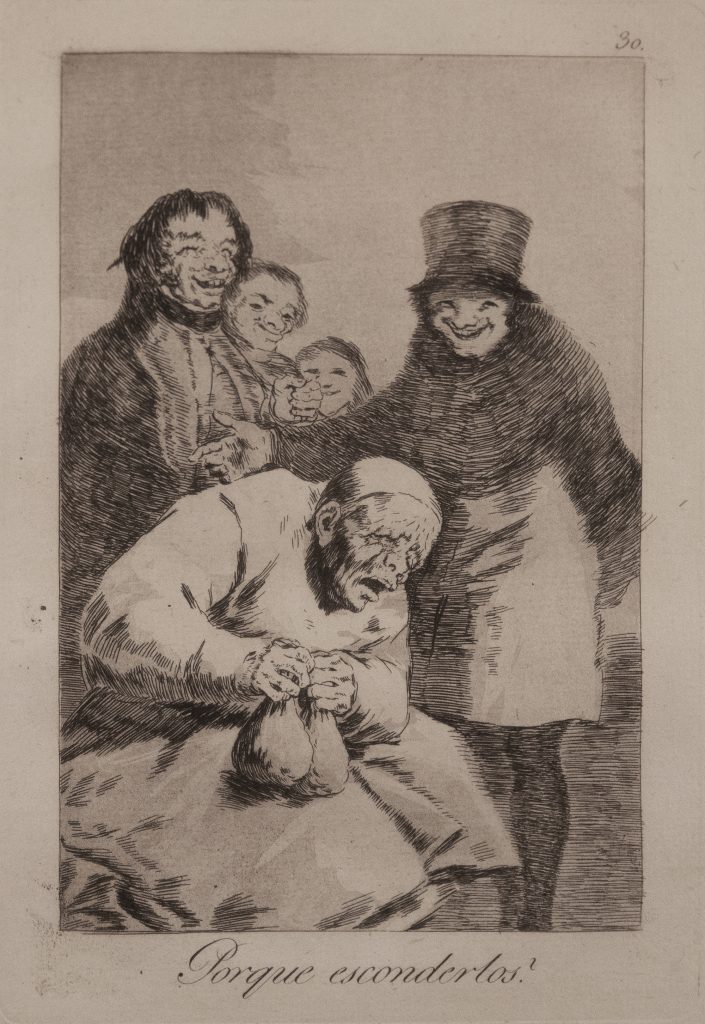

Francisco Goya (1746-1828)

Porque esconderlos? (Why Hide Them?) (1797-1798), plate 30 from Los Caprichos (1799)

Engraving and aquatint

8 7/16 × 5 15/16 (21.4 × 15.1 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Los Caprichos embodies the rationality of the Enlightenment in both its social criticism and its print technique. Goya’s mastery of the new process of aquatint, to create a contrast between light and dark, informs a gloomy portrayal of a decadent society in need of enlightenment. Although Los Caprichos has since become a canonical work of art, Goya only managed to sell some twenty-seven of two hundred forty copies printed. Although he feared that the series would provoke the Spanish Inquisition, the plates were ultimately sold to the Spanish crown in 1803.

In the thirtieth plate of Los Caprichos, Goya depicts an old man clutching two bags full of money while a crowd of younger well-dressed men, presumably his heirs, laugh behind him. The old man’s face is skeletal and his back hunched, suggesting that death is near. Moreover, the obsession with wealth will provide no solace in his last hour.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Felisati, D., and Giorgio Sperati. “Francisco Goya and His Illness.” Acta Otorhinolaryngol Italica 30 (2010): 264-270

Schulz, Andrew. Goya’s Caprichos: Aesthetics, Perception, and the Body. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005

Honoré Daumier (1808-1879)

La Seine est une rivière qui prend sa source … (1842)

Lithograph

8 × 10 5/8 (20.3 × 27 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Perhaps the best-known political cartoonist of all time, Honoré Daumier produced several thousand lithographs and etchings, often to skewer the French aristocracy’s corruption or to sympathize with the plight of the working class. Daumier contributed regularly to various journalistic publications, including La Caricature and Le Charivari. His biting caricatures of King Louis-Philippe ultimately landed him in prison (1832), where he continued sketching satires for publication. After Louis-Philippe imposed stricter censorship in 1835, Daumier was forced to abandon criticism of the crown and focus instead on lambasting the foibles of the bourgeoise.

La Seine, originally published in Le Charivari in 1839 as part of a series titled Les Baigneurs, depicts a rambunctious crowd of men bathing in the Seine. The caption reads: “The source of the Seine is the Cote d’Or, and it empties into the channel. On its way it traverses Paris where the inhabitants escape the summer’s heat and try to find freshness and purity in this river.” Daumier’s startling portrayal of personal hygiene ironizes the quest for “freshness and purity” in the river.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Noack, Dieter, and Lillian Noack. The Daumier-Register

John Sloan (1871-1951)

Roofs, Summer Night (1906)

Etching

9 3/16 × 10 7/8 (23.4 × 27.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Though originally from the American middle class, John Sloan became intimately acquainted with the life of a laborer as a youth. At sixteen, as a consequence of his father’s mental breakdown, Sloan became the breadwinner for his family, dropping out of school in order to work. The adversity of this experience combined with his belief that the political system was profoundly elitist, “the Plutocracy’s government,” drove him to join the Socialist Party of America. An advocate against classism, Sloan had a brief stint working as an illustrator for the socialist magazine The Masses. But, suspicious of propaganda, Sloan resigned from this post after four years, reflecting his desire to uplift, though not indoctrinate or inflame, America’s impoverished population.

A pioneer of the “Ashcan School” of painting, Sloan garnered acclaim for his gritty, unapologetic portrayals of the working-class. Roofs, Summer Night is one of thirteen etchings in New York City Life (1911), a starkly realistic series that captures the struggles of American urban life. Having only crammed, hot apartments, laborers cluster on top of exposed, sooty roofs, desperately seeking a cooler place to sleep. In addition to this socioeconomic malaise, human drama is lurking in the image: a man (near the right border) dreams with eyes wide open, staring longingly at another’s wife. This man is often thought to be a self-portrait of Sloan. Although an avowed socialist, Sloan stated that New York City Life promoted no political message. However, the subjects’ silent dignity in the face of destitution subtly pleads for amelioration of the plight of the proletariat.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Elzea, Rowland, and Elizabeth Hawkes. John Sloan: Spectator of Life. Delaware: Delaware Art Museum, 1988

Loughery, John. John Sloan, Painter and Rebel. New York: H. Holt, 1995

Mecklenburg, Virginia M., et al. Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and Their New York, 1897-1917. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996

Morse, Peter. John Sloan’s Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Etchings, Lithographs and Posters. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1969

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012)

A Second Generation (1992), illustration in Margaret Walker’s For My People (1942)

Color lithograph

15 3/4 × 13 11/16 (40 × 34.8 cm)

Acquired with funds from the Jack May Print Fund

Collection of Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery

Elizabeth Catlett, an influential printmaker, sculptor, educator, and activist, often portrayed the experience of black Americans in her art. Her style engages the Modernist tradition in its mixture of abstraction and figural designs, as well as in her adoption of African and Mexican artistic conventions. As an activist, Catlett felt that art should focus on issues of social and political injustice. In 1992, she created six color lithographs, including A Second Generation, to illustrate Margaret Walker’s classic For My People, a 1942 poem that powerfully recounts the black experience in America. In recognition of this work Walker was awarded the Yale Younger Poets’ Prize, becoming the first black poet to receive this honor. In A Second Generation, two busts in profile framed by bright orange show a man and a woman gazing with gravity and determination into the future. Below, figures in blue silhouette march in protest. This composition captures the last stanza of the poem, an invocation of a new generation to revolutionize society:

Let a new earth rise. Let another world be born. Let a

bloody peace be written in the sky. Let a second

generation full of courage issue forth; let a people

loving freedom come to growth. Let a beauty full of

healing and strength of final clenching be the pulsing

in our spirit and our blood. Let marital songs

be written, let the dirges disappear. Let a race of men now

rise and take control.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Graham, Maryemma. “Margaret Walker: Fully a Poet, Fully a Woman (1915-1998).” The Black Scholar 29 (1999): 37-46

Herzog, Melanie Anne. Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000

Herzog, Melanie Anne. “Elizabeth Catlett: Inheriting the Legacy.” In Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance, ed. Amy Helene Kirschke, 205-238. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014

Lewis, Samella. The Art of Elizabeth Catlett. Claremont, CA: Hancraft Studios, 1984