VI. Comic Ink

VI. Comic Ink

Much more than other visual artists, print artists have gravitated (or we should say “levitated”) toward humor, displaying a pronounced predilection for exaggerating the foibles of people and society for comic effect. A medium that lends itself to immediacy and broad dissemination, the print is ideally suited for capturing endearing imperfections of our world in a way that provides entertaining diversion from the travails of life or an amusing challenge to our feelings of self-importance.

Often requiring much less investment of time than painting, printmaking can be a low-risk endeavor that allows artists to experiment with the creation of light-hearted images. Even so, for many satirically minded artists the etching needle became a sharp instrument indeed. Above all, as best known in the American weekly The New Yorker, the humorous print has become a staple of journalistic publishing.

Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533)

Young Woman and Old Fool (1520)

Etching and engraving

4 1/16 × 2 7/8 (10.3 × 7.3 cm)

Collection of Jack May

In both technique and style, Lucas van Leyden was an imitator and (friendly) rival of Albrecht Dürer. Young Woman and Old Fool demonstrates the artist’s exceptional technical ability to combine engraving and etching. Van Leyden’s light-hearted theme is a variation on the Renaissance stereotype of the mismatched couple, one of whom is old and wealthy while the other is young and greedy. Wearing the garb of a fool (coxcomb and crown hood), a lecherous man tries to force a kiss on a young woman. Though she resists his advances, she cannot help glancing at the oversized purse hanging from his belt.

Sophia Moak

Mechanical Engineering

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Filedt Kok, Jan Piet. Lucas van Leyden Grafiek. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1979

Jacobowitz, Ellen S., and Stephanie Loeb Stepanek. The Prints of Lucas van Leyden and His Contemporaries. Washington, D. C.: National Gallery of Art, 1983

Strauss, Walter L. The Illustrated Bartsch. Vol. 13 (Hans Baldung Grien, Hans Springinklee, Lucas van Leyden). New York: Abaris, 1981

Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827)

Chamber of Genius (1806)

Hand-colored etching

10 5/16 × 15 5/16 (26.2 × 38.9 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Chamber of Genius depicts an inspired artist absorbed in his creation. Though painting furiously (and obliviously), our artist is no solitary genius, for he finds himself in the eye of a household hurricane: a child pours himself a drink, another stokes the fire, a cat assails his legs, and his foot knocks over a chamber pot, all within a room overstuffed with everything from a classical bust to a violin, symbols of inspiration and ingenuity. Moreover, a rapier and a tricorn hat, precariously balancing on a wall, may indicate a previous life as a soldier. In all of the commotion, our genius fails to recognize that the prophet (or demon?) he is painting has morphed into a self-portrait. A zany caricature of transcendent aspirations, Chamber of Genius parodies the Romantic ideal of the artist shunning worldly concerns in the pursuit of pure art.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Grego, Joseph. Rowlandson the Caricaturist: A Selection from His Works. London: Spottiswoode and Co., 1880

Sherry, James. “Distance and Humor; The Art of Thomas Rowlandson.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 11 (1978): 457-472

Stephens, F. G. “Thomas Rowlandson, The Humourist.” The Portfolio: An Artistic Periodical 22 (1891): 141-148

John Sloan (1871-1951)

The Woman’s Page (1905)

Etching

5 x 6 7/8 (12.7 x 17.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Characteristic of Sloan’s peeking-through-the-window compositions from his New York City Life series, The Woman’s Page provides an entertaining glimpse into a home in disarray. A child plays unattended on an unmade bed, stockings hang from the window frame, and domestic objects litter the floor. While her washboard and tub rest unattended on the left, the lady of the house sits engrossed in “A Page for Women,” a glossy review of high fashion and home decorating tips, the glamorous life of the wealthy. As entertaining as this print is, we might be grateful that the sexist “Women’s Section” is no longer a standard part of newspapers, even though media glorification of the wealthy and ritzy still flourishes.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Kinser, Suzanne L. “Prostitutes in the Art of John Sloan.” Prospects 9 (1984): 231-254

Brooks, Van Wyck. John Sloan: A Painter’s Life. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1955

Morse, Peter. John Sloan’s Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Etchings, Lithographs and Posters. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1969

Peggy Bacon (1895-1987)

The Promenade Deck (1920)

Drypoint

16 × 20 (40.65 × 50.8 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Peggy Bacon’s studies with John Sloan at the Art Students League made a strong impact on her style, particularly as she developed her gift for witty caricature. The Promenade Deck, which was included in The New Republic’s “Six American Prints” collection, was Bacon’s breakthrough into the mainstream. The image presents a view of the S. S. New Amsterdam in her distinctive cartoony stylization. Intended for strolling and relaxing, the promenade deck is so crowded with people that either activity is unthinkable. One can only imagine the cacophony of children scrambling, smoking men arguing, and the litany of “pardon me” as people navigate the deck. The two figures seen sketching in the lower right corner are thought to be Bacon and her husband. The print simultaneously mocks the pretentiousness of the transatlantic cruise and, by including the artist, suggests that nobody is above parody.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Bacon, Peggy. Peggy Bacon: Personalities and Places. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1975

Flint, Janet A. Peggy Bacon: A Checklist of the Prints San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 2001

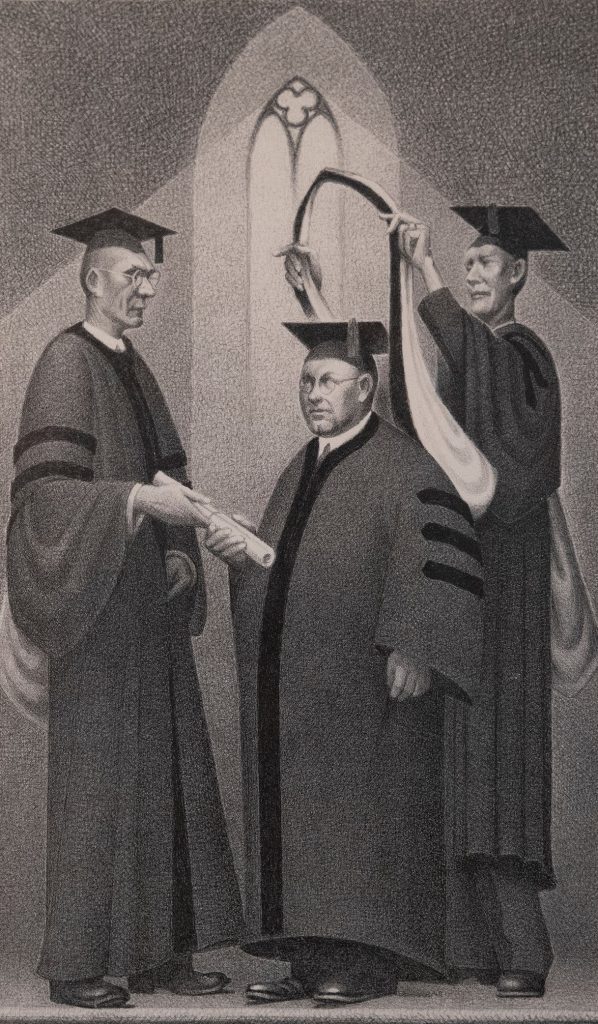

Grant Wood (1891-1942)

Honorary Degree (1938)

Lithograph

11 15/16 × 6 7/8 (30.4 × 17.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Following the initial display of his iconic painting American Gothic (1930) at the Art Institute of Chicago, Grant Wood experienced an instantaneous surge of fame. In the wake of his sudden celebrity, he was awarded a series of honorary degrees, beginning with a Doctor of Letters from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1936. In Honorary Degree, the central figure, recognizable as the artist from his round glasses and cleft chin, uncharacteristically dons doctoral robes. (Wood was a notable devotee of denim overalls.) Stereotypes of the high and mighty academic, the tall figures bestowing the degree are juxtaposed with the exaggeratedly short Wood. Herein lies the humor: although the artist was immensely skilled and creative, he received little formal education. In this print, however, “Mr. Dope” (as one art critic dubbed Wood) finds himself exalted through the pomp and circumstance of academia. Nicknamed “Scholastic Gothic,” Honorary Degree also pays homage to the source of Wood’s fame—the pointed stole and the arched window in the background are direct references to the Carpenter Gothic farmhouse of his most famous painting.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

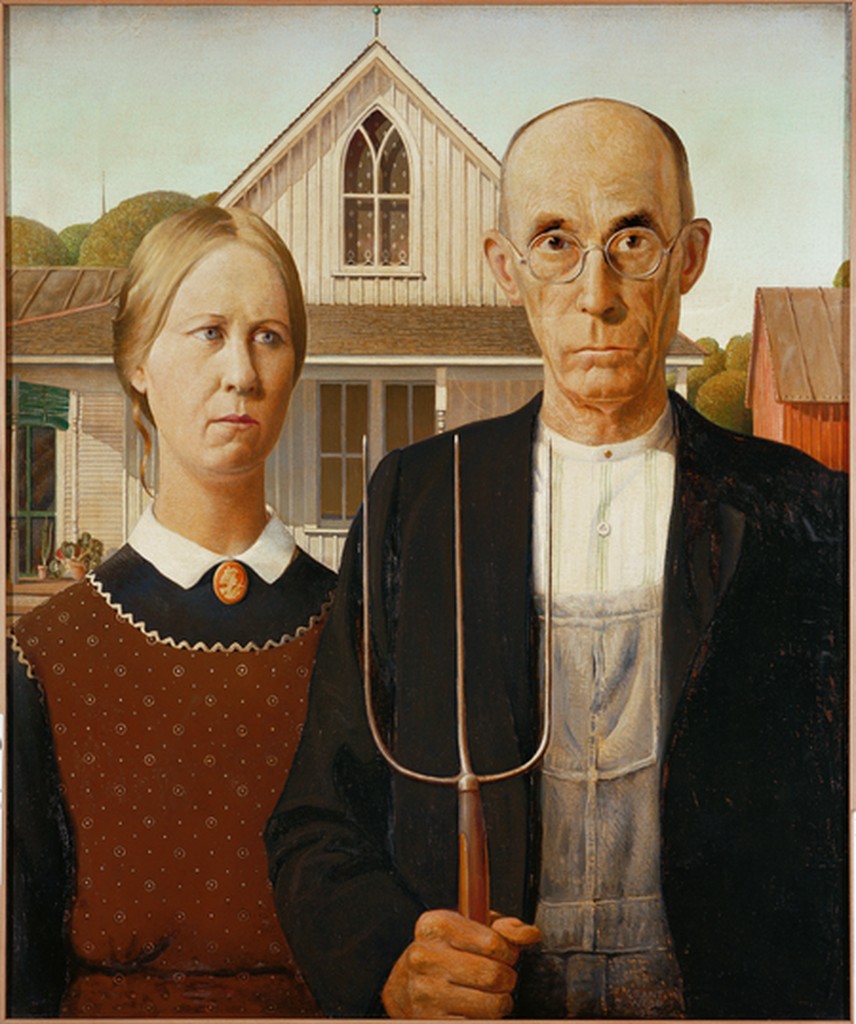

Grant Wood (1891-1942), American Gothic (1930). Oil on beaverboard, 30 3/4 × 25 3/4 (78 × 65 3/10 cm)

The painting that elevated Wood to stardom.

Recommended Sources

Cole, Sylvan, and Susan Teller, ed. Grant Wood: The Lithographs. New York: Associated American Artists, 1984

Johnson, Bruce E. Grant Wood: The 19 Lithographs, A Catalogue Raisonné. Fletcher, NC: Arts and Crafts Research Fund, 2016

Myers, Donald. Grant Wood’s Lithographs: A Regionalist’s Vision Set in Stone. St. Peter, MN: Hillstrom Museum of Art, 2015

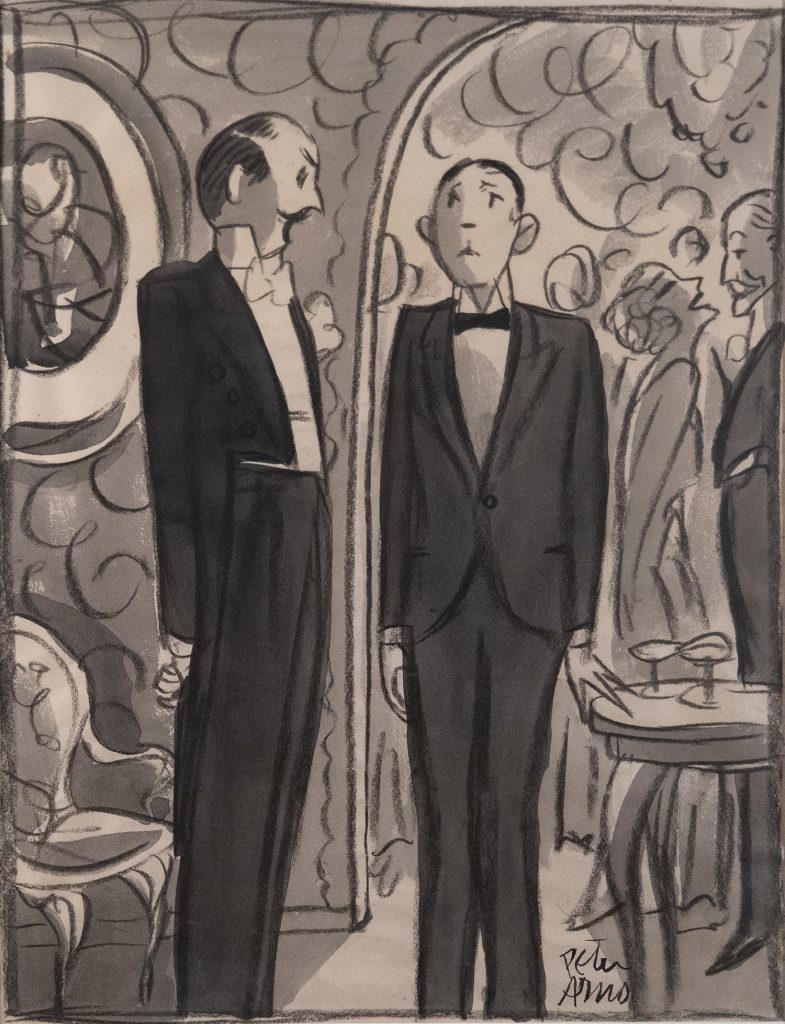

Peter Arno (1904-1968)

I Wouldn’t Go to Harvard (ca. 1932), reproduced in The New Yorker (September 10, 1932)

Drawing with pen and ink

13 1/4 x 8 1/2 (33.7 cm x 21.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Peter Arno created hundreds of cartoons and some ninety-nine covers for The New Yorker magazine between 1925, the first year of its publication, and his death in 1968. His satires of the extreme privilege of New York City socialites helped to establish the magazine’s reputation as an engaging journal of literature as well as political and cultural criticism. In this print, a young man stands at attention at a lavish social event while an elegantly attired patriarch opines on college prospects, the only choices of course being Yale or Harvard: “I wouldn’t go to Harvard, Briscomb. You have a fine sense of humor – why take any chances with it?” In the hazy, smoke-filled background, society’s elite converse, flirt, and indulge. Though a former Yale student himself, Arno uses gag humor to trivialize the academic value of elite education, lampooning it solely as a source of social capital.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Balk, Eugene. “The ‘American Scene’ Print and the Cartoon.” Print Quarterly 11 (1994): 379–394

Maslin, Michael. Peter Arno: The Mad, Mad World of The New Yorker’s Greatest Cartoonist. New York: Regan Arts, 2016

Topliss, Iain. “Peter Arno: The Last Days of Cabaret.” In The Comic Worlds of Peter Arno, William Steig, Charles Addams, and Saul Steinberg, 21-73. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2005

Red Grooms (b. 1937)

Truck II (1979)

Color lithograph, screenprint, and rubber stamp

24 3/8 x 63 (61.9 cm x 160 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Red Groom’s Truck II possesses an almost onomatopoeic quality, immediately bringing to mind the sound of rubber tires rumbling over the cobbled streets of a busy city. There is humor in the juxtaposition of delicate female hosiery being transported by a boxy, masculine vehicle. While Truck II presents a boisterous depiction of the hustle and bustle of New York City, Grooms himself is a notable Nashville native. A graduate of Hillsboro High School and the George Peabody School for Teachers (now part of Vanderbilt University), Grooms might be best remembered by Nashville residents for his Tennessee Foxtrot Carousel (1998), which used to spin alongside the Nashville Riverfront. Notably, one of the figures on the carousel was Jack May’s father, Dan May, a Nashville Councilman-At-Large, member of the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, and President of the May Hosiery Mills.

Though the black linework was added using lithography (as seen in Groom’s black-and-white Truck (1979)), the color was produced by screenprint. To make a screenprint, ink is forced through a mesh screen onto the desired ground, usually paper or cloth. The screen, usually a piece of fine mesh fabric (traditionally silk and now usually polyester) tightly stretched on a frame, is made selectively permeable by applying stencils. During the printing process, the artist dollops ink on the mesh and then squeegees it through the screen with a rubber blade. Multi-colored screenprints usually require registration and repeating the process for each color, as in colored lithographs.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Knestrick, Walter, and Vincent Katz. Red Grooms: The Graphic Work. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2001

Pacini, Marina, and Susan W. Knowles. Red Grooms: Traveling Correspondent. Memphis: Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, 2016