II. People

II. People

Johannes Gutenberg’s development of the printing press in Europe launched a visual revolution. With the new capacity to reproduce images, it became possible to appreciate what distant people, places, and things looked like. The portrait print gained tremendous popularity, allowing viewers to see contemporary and historical celebrities they could never hope to encounter in real life. In their portraiture, print artists express not only likeness but also the psychology and philosophy of both their subjects and themselves.

The May Collection features several portraits of famous cultural and political figures as well as ordinary people. In particular, Jack May often acquired significant portraits of leading artists, artisans, and art dealers.

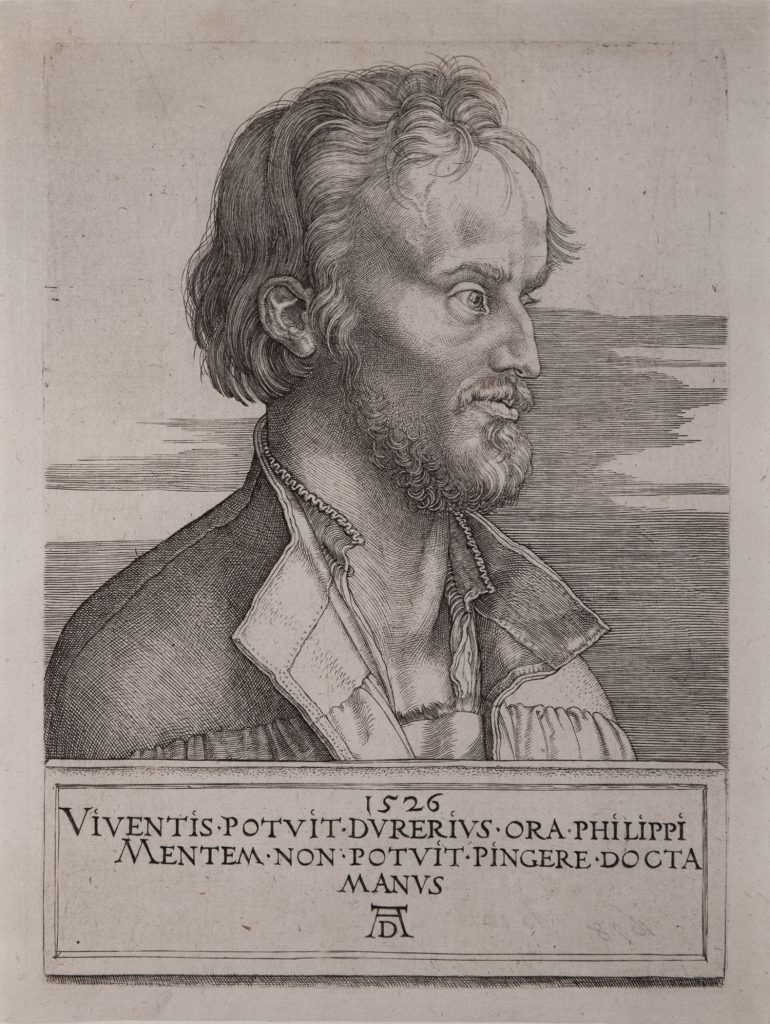

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528)

Philipp Melanchthon (1526)

Engraving

6 7/8 × 5 (17. 4 × 12.7 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Albrecht Dürer is often considered the founding artist of the Northern Renaissance. His engraved portrait of Philipp Melanchthon, a humanist professor and colleague of the reformer Martin Luther, emphasizes the scholar’s intellect, portraying an expansive mind that radiates through the skull. Widely viewed as a leading authority on ancient Greek, Melanchthon collaborated with Luther on the epochal German translations of the Bible and was instrumental in establishing Protestant doctrine. The scholarly focus of Dürer’s composition extends to the inscribed Latin verse, which states “Dürer was able to depict the features of the living Philipp, but the skilled hand could not portray his mind.” Dürer’s portrait adopts an important propagandistic strategy by portraying the Reformation as an intellectual movement, ultimately grounded in the scholarly study of the Bible.

The portrait style, derived from the Italian Renaissance, evokes bas-relief epitaph sculpture from Roman antiquity.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersions Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Meder, Joseph. Dürer-Katalog. Vienna: Gilhofer and Ranschburg, 1932

Panofsky, Erwin. The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955

Price, David H. Albrecht Dürer’s Renaissance: Humanism, Reformation, and the Art of Faith. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003

Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617)

Agatha Scholiers (1586)

Engraving

6 3/16 × 4 3/4 (15.7 × 12.1 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Hendrick Goltzius became a prolific and successful artist, even though his right hand was severely burned and disabled in his youth. Altogether, some 361 prints and thirty-nine paintings survive from his oeuvre. He is considered the most significant Dutch engraver of the early Baroque, an influential artist who introduced the Italian Mannerist style to the North.

This portrait of his mother-in-law, Agatha Scholiers, incorporates essential aspects of his style, most noticeably his distortion of proportions (as in the arms and shoulders) in the manner of Michelangelo. In this print, he also adapted the portrait genre into an aphoristic emblem, in this case, one that is enigmatically pessimistic. The Latin inscription, which is a quote from one of Horace’s Odes, gives the parental portrait a curious twist: “What does ruinous time not diminish? The generation of our parents, worse than our grandparents, produces us, more worthless, and we will soon create an even more wicked progeny.”

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Walter L. Strauss. Hendrik Goltzius: The Complete Engravings and Woodcuts. New York: Abaris, 1977

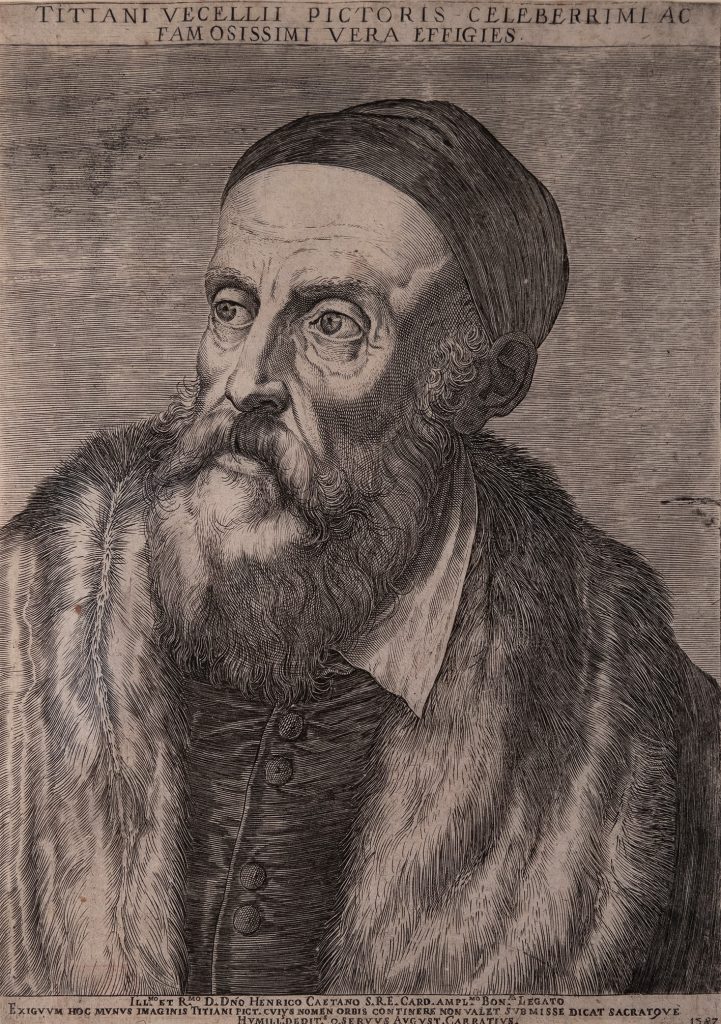

Agostino Carracci (1557-1602)

Portrait of Titian (1587)

Engraving

12 3/4 × 9 1/8 (32.4 × 23.2 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Before the advent of photography, printmakers reproduced copies of significant paintings. Although reproductive engraving primarily functioned as a way to increase the knowledge and appreciation of major paintings, some of these prints also deserve to be considered as works of art in their own right.

Agostino Carracci copied several works by the grand masters including Titian, Correggio, and Veronese, usually adapting them to strengthen their impact in the print medium. Likely based directly on Titian’s self-portrait (1546-47), Carracci’s engraved Portrait of Titian (1587) alters the original by dramatically cropping the composition. He has also introduced a costume change—a plain white shirt and chain have been swapped for a dark satin coat and dramatic fur ruff. Carracci uses broad burin cuts and long, curved lines to suggest the textures of these fine materials. Additionally, the figures in the painted and printed portraits face in opposite directions, illustrating a challenge unique to reproductive printmaking. If the engraver directly copies the original on the printing plate, the transfer from the plate to the printing ground will produce a mirror image of the original picture.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Titian (1490-1576), Self Portrait (ca. 1546-47). Oil on canvas, 37 7/10 × 29 1/2 (96 × 75 cm)

Recommended Sources

De Grazia Bohlin, Diane. Prints and Related Drawings by the Carracci Family: A Catalogue Raisonné. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1979

Foratti, Aldo. I Carracci nella Teoria e nella Practica. Castello: S. Lapi, 1913

Goldstein, Carl. Visual Fact over Verbal Fiction: A Study of the Carracci and the Criticism, Theory, and Practice of Art in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641)

Frans Francken II (before 1641)

Etching and engraving

9 5/8 × 6 1/4 (24.3 × 15.8 cm)

Collection of Jack May

The vibrant painter of nobility Anthony van Dyck created just a few portrait prints, all of which were for his Iconographia (ca. 1632-1644), a set of etchings of famous people, including several artists. The half-length rendering of the Flemish painter Frans Franken II is an excellent example of van Dyck’s innovative “unfinished” style, an approach that dramatically focuses only on selected aspects of the subject, usually features of the face. Franken appears here as a powerful and dignified man of substance with no reference to his artistry. The framing pilaster, with cracks forming on its surface, is probably symbolic of van Dyck’s Christian Neo-Stoicism, a philosophy that taught the importance of preserving constancy and acceptance amid a turbulent and imperfect world.

Margaret Sturm

Economics

Class of 2023

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Jaffé, Michael. “Van Dyck, Anthony.” Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford Art Online, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/

Lobis, Victoria Sancho. Van Dyck, Rembrandt, and the Portrait Print. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 2016

Mauquoy-Hendrickx, Marie. L’Iconographie d’Antoine van Dyck: Catalogue Raisonné. 2 vols. 2nd ed. Brussels: Bibliotheque Royale Albert, 1991

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Portrait of Jan Lutma, Goldsmith (1656)

Etching with drypoint and engraving

7 7/8 × 5 7/8 (20 × 15 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Rembrandt van Rijn’s deeply empathetic Portrait of Jan Lutma, Goldsmith contrasts the fragility of the aging Lutma with the timeless virtuosity of his artwork. Lutma, who went blind in his old age, retains his warmth and dignity. His wrinkles, captured so effectively by Rembrandt’s sentimental etching needle, harken to Lutma’s experience and thoughtfulness. Rembrandt clearly admired the man as a master gold- and silversmith, taking care to include both Lutma’s own work and the tools of his trade in the portrait. Notably, the small bowl on the table is an example of Lutma’s innovative Auricular style, which is characterized by its ornamental curves and smooth forms that resemble the human ear.

Rembrandt depicts not only the sitter’s physical likeness but also evokes an “inner portrait” of the subject’s character and personality. Lutma, leaning against the back of his chair, communicates a sense of dignified weariness. Similarly, the dramatic lighting, which highlights the man’s hands and temples, prompts viewers to consider the craftsman’s inner psyche. Even in his old age, the Lutma of Rembrandt’s depiction embodies a sense of artistic vitality, able to make use of his mind and hands.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Dickey, Stephanie S. Rembrandt: Portraits in Print. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2004

Schatborn, Peter, and Erik Hinterding. Rembrandt: The Complete Drawings and Etchings. Cologne: Taschen, 2019

Michel, Emile, Vladimir Loewinson-Lessing, Irena Linnik, Youri Kouznetsov, and Xenia Egorova. Harmensz van Rijn Rembrandt. London: Sirrocco, 2002

Schama, Simon. Rembrandt’s Eyes. London: Penguin Press, 2000

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

Simon Lord Lovat (1746)

Engraving

14 11/16 × 9 11/16 (37.3 × 24.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

William Hogarth spearheaded the 1734 Engravers’ Copyright Act, a major advance for print artists that granted copyright ownership to the original designers of prints, rather than to the printers. As a result, Hogarth realized substantial commercial success by selling engravings of his paintings, especially his popular satires of depravity.

Originally a portraitist and moralist, Hogarth rose to prominence initially on the strength of his elegant depictions of British aristocrats and his heart-wrenching images of squalor. His social conscience and activism never diminished. He tried to catch the public’s eye and instigate change by satirizing rather than dramatizing corruption. Thus, beginning in the late 1730s, Hogarth began to abandon his previously austere paintings for lighter, more accessible prints that convey an equally powerful criticism of society, such as his humorous portrait of Simon Lord Lovat.

The 11th Lord Lovat, Simon Fraser earned the sobriquet of “the Fox” and the reputation of being “the most devious man in Scotland” for alternately supporting and betraying the British crown. In Hogarth’s depiction, Fraser is writing a memoir and counting on his fingers, perhaps trying to keep track of his crimes and transgressions. No easy task, for in his lifetime Fraser usurped an aristocratic title, kidnapped a cousin and forced her to marry him, and supported both sides in the Jacobite Uprisings and Revolution. Ultimately charged with treason, he was the last man in Britain to be publicly beheaded outside the Tower of London. With the caricature of Fraser’s conniving and sinister countenance, Hogarth renders his portrayal of treachery comical.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Bindman, David. Hogarth and His Times: Serious Comedy. London: British Museum Press, 1997

Mackenzie, William Cook. Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat: His Life and Times. Charleston: Nabu Press, 2010

Paulson, Ronald. Hogarth’s Graphic Works. Catalogue Raisonné. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1989

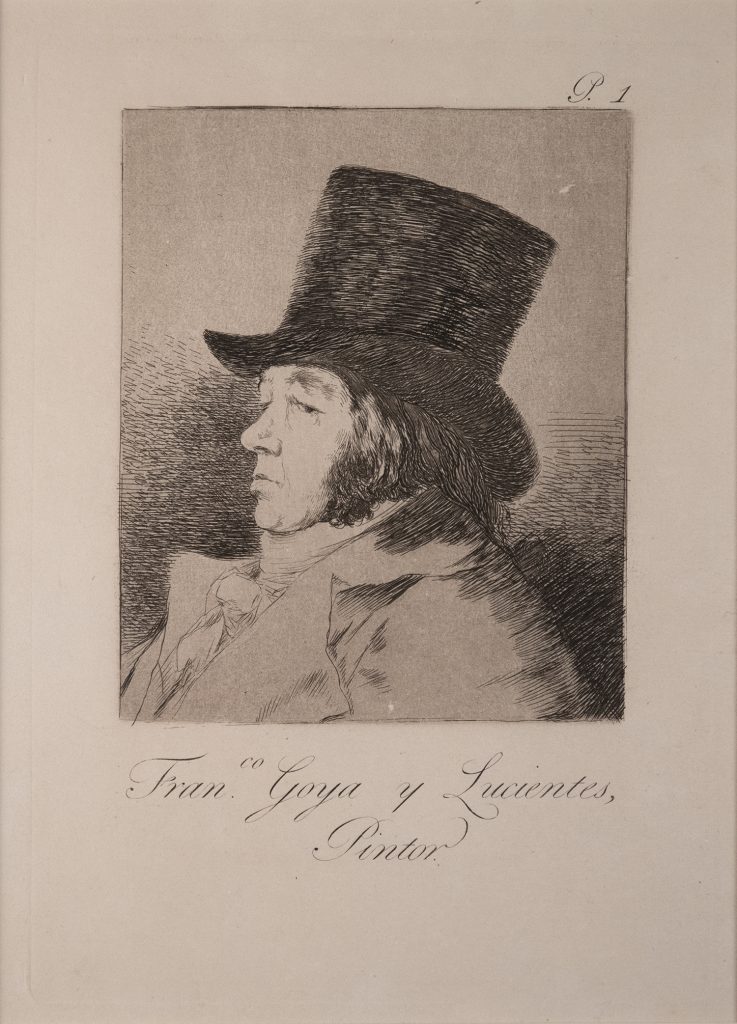

Francisco Goya (1746-1828)

Self-Portrait (1799), plate 1 from Los Caprichos (1799)

Engraving and aquatint

8 1/2 × 5 15/16 (21.7 × 15 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Goya is recognized as one of the finest portraitists of his time. A celebrated court artist, his most famous portraits are paintings of the royal family and other aristocrats of Spain. In this print, however, he portrays himself, “Francisco Goya y Lucientes, Painter” (inscription), as a simple, albeit well-dressed, middle-aged Spaniard. Noted for the honesty of his likenesses, Goya accurately depicts his own distinctive facial features, in particular his snub nose and deep-set eyes. As the introductory image to his satirical print series Los Caprichos, the self-portrait sports that “critical sidewise cock of the eye” (in Jack May’s words), perhaps to set the tone for his exposé of the failings in contemporary Spanish society.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Muller, Priscilla E. “Goya (y Lucientes), Francisco (José) de.” Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford Art Online

Pop, Andrei. “Goya and the Paradox of Tolerance.” Critical Inquiry 44 (2017):242–74

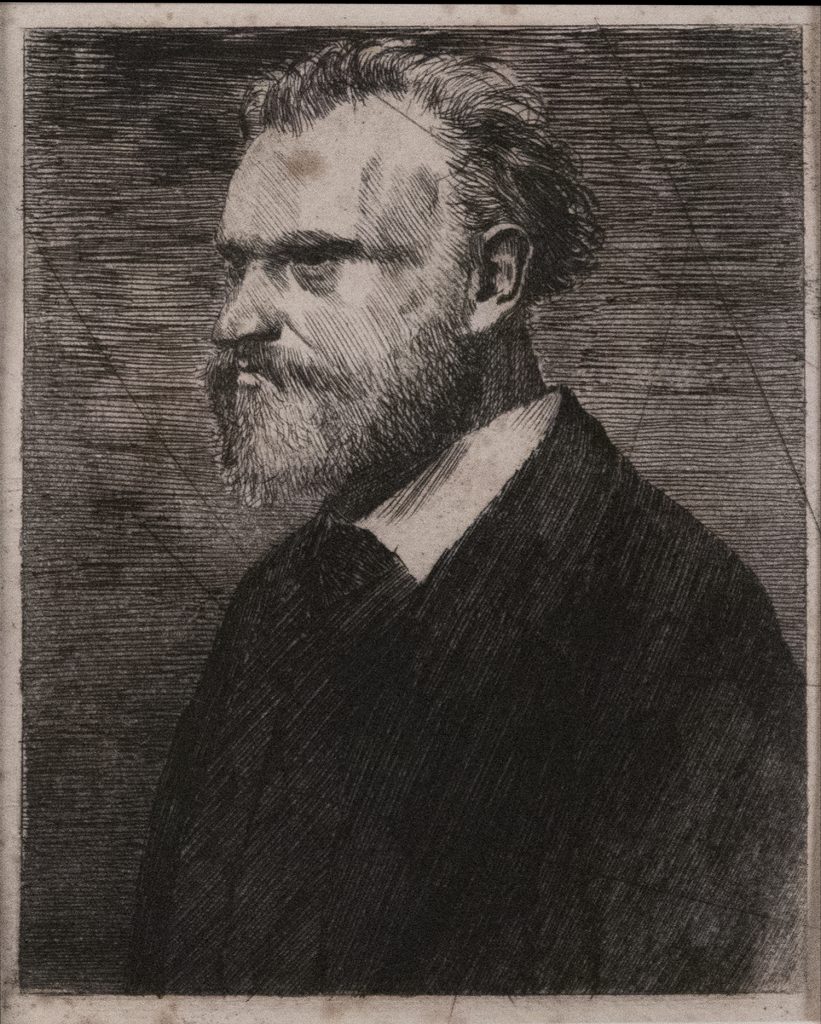

James A. McNeill Whistler (1834-1903)

Drouet (1859)

Etching and drypoint

14 1/16 × 9 1/2 (35.7 × 24.1 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Thoughtful. Powerful. Influential. These are the characteristics evident in Whistler’s portrait of Charles L. Drouet, a minor sculptor whom Whistler befriended during his sojourn in Paris. The inscription identifies him as a “sculpteur,” though there are no visual indications of his profession. Yet his broad shoulders, imposing posture, and stern face portray him as a powerful intellect and visionary. Whistler etched Drouet’s sharp face and brooding eyes and then used drypoint, which creates burred lines, to render his robust arms and torso. As a result of this contrast, Drouet assumes a domineering form with a fiercely intellectual visage.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Gallatin, Albert Eugene. The Portraits and Caricatures of James McNeill Whistler: An Iconography. Seattle: Palala Press, 2016

Macdonald, Margert F., et al. James McNeill Whistler: The Etchings, A Catalogue Raisonné. Glasgow: University of Glasgow, 2012

Pennell, Joseph, and Elizabeth Robins Pennell. The Life of James McNeill Whistler. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1925

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

Édouard Manet (1864-65)

Etching, dry point, and aquatint

5 1/8 × 4 1/8 (13 × 10.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Best known for his paintings and sculptures, Edgar Degas also experimented with printmaking. In this portrait, he pays homage to fellow artist Édouard Manet, whose formal innovations and revolutionary compositions inspired the Impressionists, including Degas himself. Manet appears in a three-quarters profile, his steely gaze and strong features signaling his stature as a visionary and his resilience against criticism. The bust-length cropping, derived from a classical style of portraiture used for government and military leaders, enhances the gravitas of the portrait.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Reed, Sue Welsh, and Barbara Stern Shapiro. Edgar Degas: The Painter as Printmaker. Boston: Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 1984

Shunkōsai Hokushū (active, ca. 1810-1832)

Actor in Blue (1815)

Color woodblock print

10 x 7 1/4 (25.4 cm x 18.4 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Celebrated for his portrait prints, which established him among the most prominent artists of the Osaka style, Shunkōsai Hokushū is remembered as an influential maker of yakusha-e, portraits of kabuki actors in character. Actor in Blue captures the grandiose effect of the performer’s makeup and facial expression. His pose, the prayer beads (juzu beads), and the pail suggest a suspended narrative and imply that this scene has been lifted directly from the stage. The unconventional perspective and the theatrical subject matter are typical of the ukiyo-e genre. Ukiyo-e, which translates as “pictures of the floating world,” was associated with colorful prints of hedonism. Following the end of Japan’s isolationist practices in 1858, European Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists adopted elements of ukiyo-e in a trend known as Japonisme.

The inscription identifies the actor as Yumi Kazumi, who died at the age of fifty, possibly before this portrait was made.

Chloe Davis

Class of 2020

History of Art and Anthropology

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Breuer, Karin. Japanesque: The Japanese Print in the Era of Impressionism. Munich: Prestel, 2010

Hartley, Craig, and Celia Withycombe. Prints from the Floating World: Japanese Woodcuts from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. London: Lund Humphries, 1997

Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World: The Japanese Print, Including an Illustrated Dictionary of Ukiyo-e. New York: Putnam, 1978

Newland, Amy Reigle. The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints. 2 vols. Amsterdam, Hotei Publishing, 2005

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901)

May Milton (1895)

Color lithograph

31 1/2 × 22 1/2 (80 × 57.1 cm)

Collection of Jack May

The most renowned poster artist of all time, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec designed this lithograph to advertise the cabarets, a new form of entertainment that emerged in nineteenth-century Paris. The poster was plastered on walls and kiosks in the Montmartre district of Paris to promote the dancer May Milton. Toulouse-Lautrec derived several compositional elements from Japanese woodblock prints, an artform that had suddenly become fashionable in Paris: the image’s uniform light and color, unconventional vantage point, May’s kabuki-esque face, and racy theme. Toulouse-Lautrec also designed a monogram signature (lower left) in imitation of the artist’s stamp on Japanese prints.

For the bourgeoisie and proletariat alike, the cabaret was a place of temporary refuge from the pressures of moral expectations. Despite the low moral status of the demimonde, Toulouse-Lautrec imbues his subject with dignity and celebrates her fame and autonomy, each gained by transgressing societal conventions. May Milton blends the risqué element of his nightlife scenes with a sensation of empowerment.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), The Blue Room (1901). Oil on canvas, 19 7/8 × 24 1/4 (50.5 × 61.6 cm)

May Milton is visible in the background of Picasso’s painting.

Recommended Sources

Wittrock, Wolfgang, and Catherine E. Kuehn, ed. Toulouse-Lautrec: The Complete Prints. New York: Harper and Row, 1985

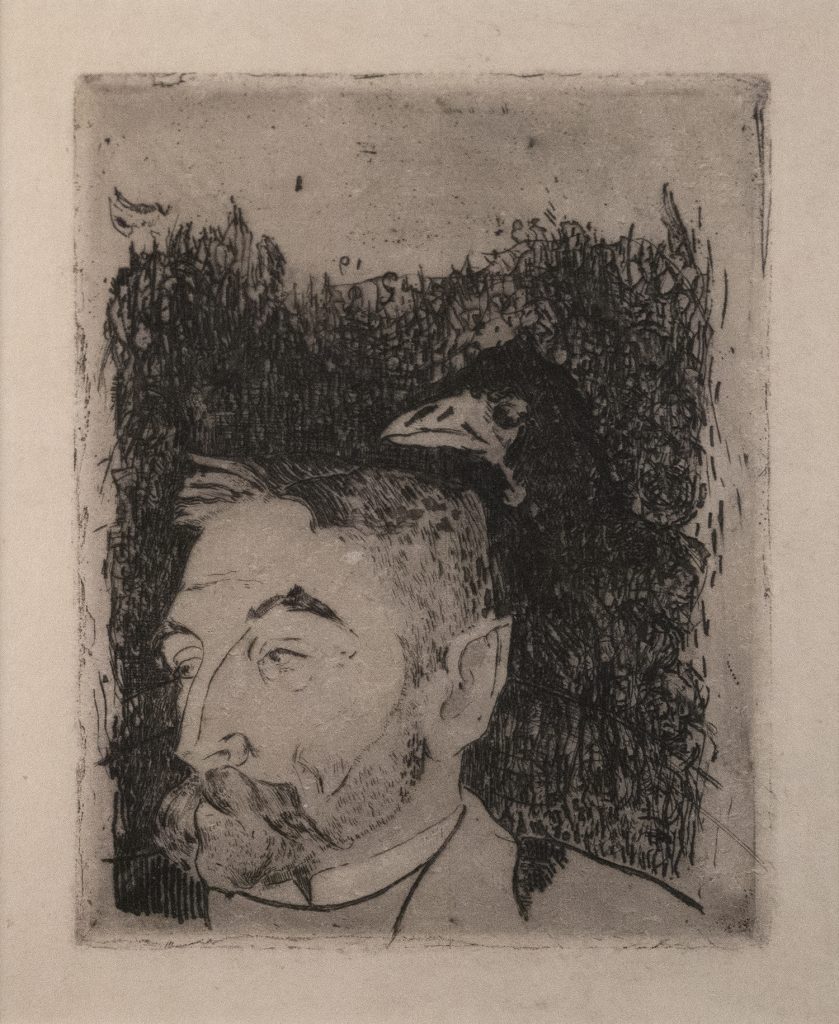

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903)

Stéphane Mallarmé (1891)

Etching

7 3/16 × 5 11/16 (18.3 × 14.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Paul Gauguin, the famed French painter and printmaker, is noted for non-naturalistic use of color and expressive distortion of formal techniques. Gauguin participated in the Symbolist movement, which held that art should symbolize and reflect emotions and ideas rather than recreate an image from nature. The Symbolists also took a strong interest in non-European art.

In this etching, Gauguin uses cross-hatching to create a deep shadow from which his subject dramatically emerges: Stéphane Mallarmé, a major poet of the Symbolist movement. A raven peers out from the shadows behind him, probably in homage to the American writer Edgar Allen Poe and to Mallarmé’s translation of Poe’s The Raven. Experts have also observed that Mallarmé’s appearance strongly resembles Gauguin’s later self-portrait: perhaps the etching casts the artist as the poet to suggest a common identification with Symbolism.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Eisenman, Stephen F. Paul Gauguin: Artist of Myth and Dream. Milan: Skira, 2008

Mongan, Elizabeth, Eberhard W. Kornfeld, and Harold Joachim. Paul Gauguin: Catalogue Raisonné of His Prints. Bern: Galerie Kornfeld, 1988

Rey, Robert. Gauguin. London: Parkstone International, 2010

Mary Cassatt (1845-1926)

Margot in a Bonnet (1902)

Dry point

9 1/4 × 6 1/4 (23.5 cm × 15.9 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Mary Cassatt, an American-born Impressionist, was among the few female artists of her era to gain wide contemporary recognition. While she was able to break into the ranks of the leading French painters, Cassatt was limited by social conventions that prevented her from holding sittings with males she was not directly related to. Thus, many of her works represent female subjects from the perspectives of motherhood and domesticity.

Margot in a Bonnet shows Margot Lux, a neighbor child, dressed in a posh dress and bonnet. The outfit, though formal, underscores Lux’s youth. The puffed sleeves echo the rolls on Lux’s arms and the bonnet accentuates her round face. Although she appears to be sitting still, her distracted gaze and open mouth indicate that her interest is starting to flag. This effort to capture a fleeting moment reflects Cassatt’s Impressionist orientation, while her choice of model asserts her commitment to portraying women’s identity.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Breeskin, Adelyn Dohme. Mary Cassatt: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Graphic Work. Rev. ed. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979

Broude, Norma. “Mary Cassatt: Modern Woman or the Cult of True Womanhood?” Woman’s Art Journal 21(2000): 36-43

Yeh, Susan Fillin. “Mary Cassatt’s Images of Women.” Art Journal 35 (1976): 359-63

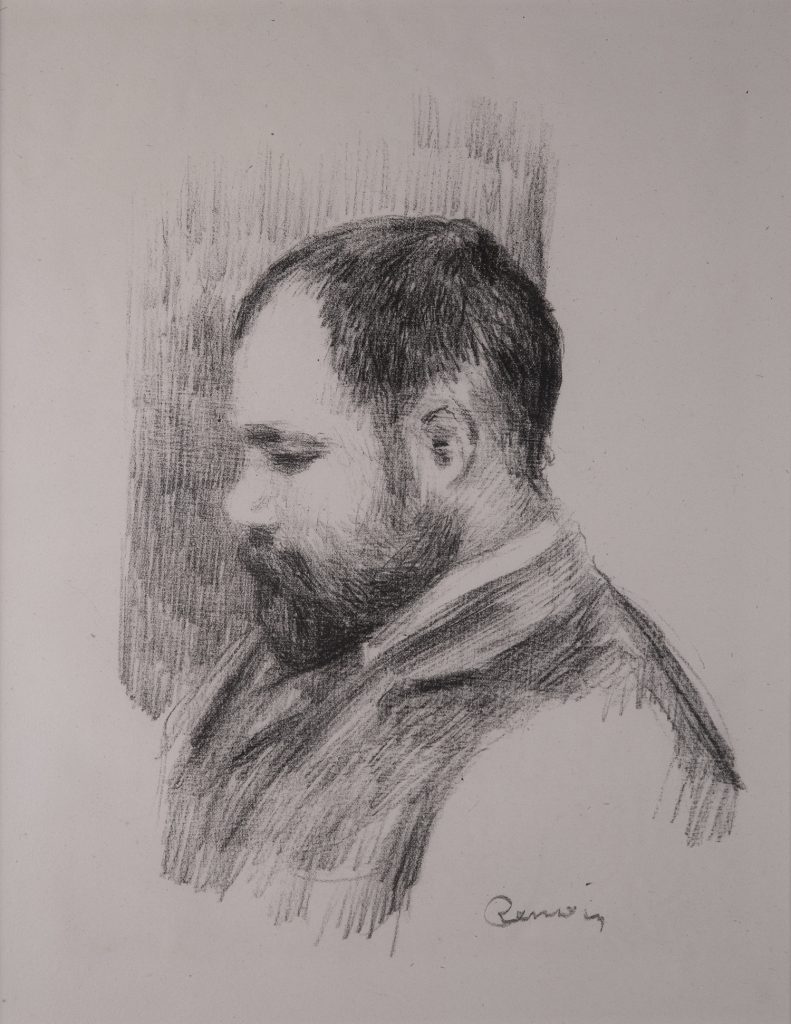

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (circa 1904)

Lithograph

14 3/8 × 10 7/16 (36.5 × 26.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

As the most influential French art dealer of the period, Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) is ubiquitous in Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art. Vollard and Pierre-August Renoir, by all accounts devoted friends, produced generous tributes to each other. Vollard portrayed the painter in an insightful biography, while Renoir depicted the dealer in several paintings as well as in this lithograph, an intimate view of his friend. The absence of setting draws the viewer directly into Vollard’s quiet contemplation. The subject appears undisturbed by the artist’s presence, suggesting a strong bond of trust and affinity. Although Renoir created the lithograph in 1904, Vollard did not publish it until after Renoir’s 1919 death, along with several other previously unseen sketches and prints.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Stella, Joseph G. The Graphic Work of Renoir: Catalogue Raisonné. Bradford: Lund Humphries, 1975

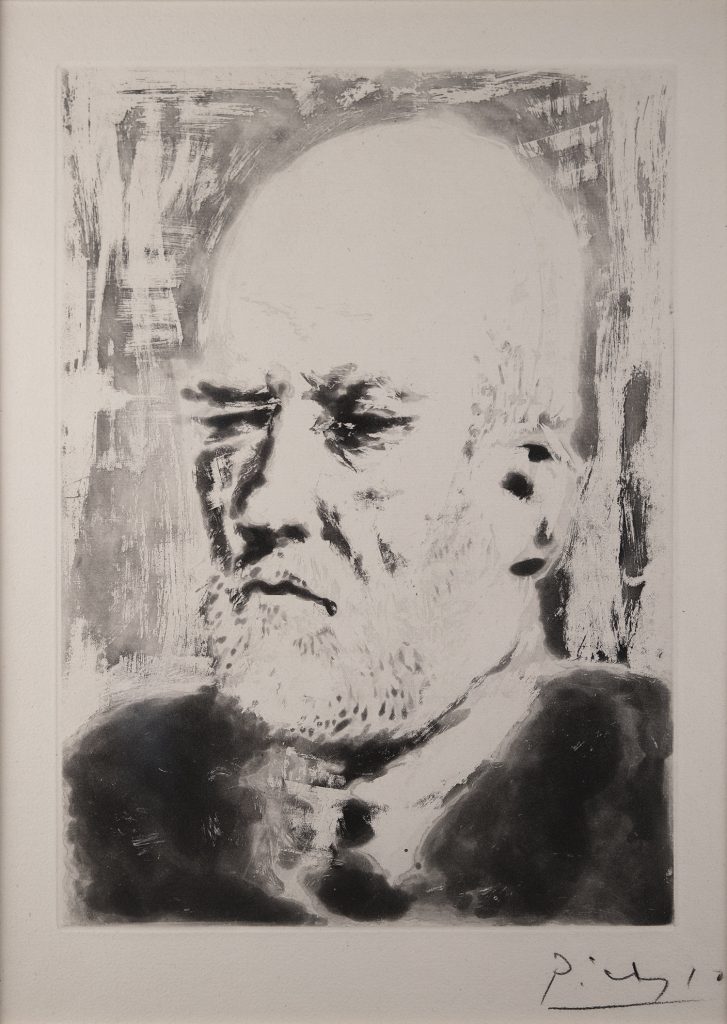

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Ambroise Vollard (circa 1937)

Aquatint

13 3/4 × 13 3/4 (35.9 × 34.9 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Ambroise Vollard, the subject of this print, was an influential proponent of European Modernism. As an art dealer, Vollard promoted the careers of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Renoir, and Picasso, among others, bringing acclaim and wealth to the artists he championed. This portrait is from a set of one hundred prints known as the Vollard Suite, a major work that reflects Picasso’s fascination with classical art. Vollard’s positioning, concentrated gaze, and the austere and heavy treatment of his head all evoke characteristics of Hellenistic portrait busts. Although Vollard died in an automobile accident just before the official publication of Picasso’s collection, the book’s three portraits of him attest to the power of his legacy.

In this print, Picasso uses “sugar-lift” aquatint, a method that allows direct application of the design to the plate.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Coldwell, Paul. “The Power of Dreams: Picasso’s Vollard Suite at the British Museum.” Art in Print 2 (2012): 34-35

Goeppert, Sebastian, Herma C. Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer. Pablo Picasso, the Illustrated Books: Catalogue Raisonné. Trans. Gail Mangold-Vine. Geneva: Patrick Cramer, 1983

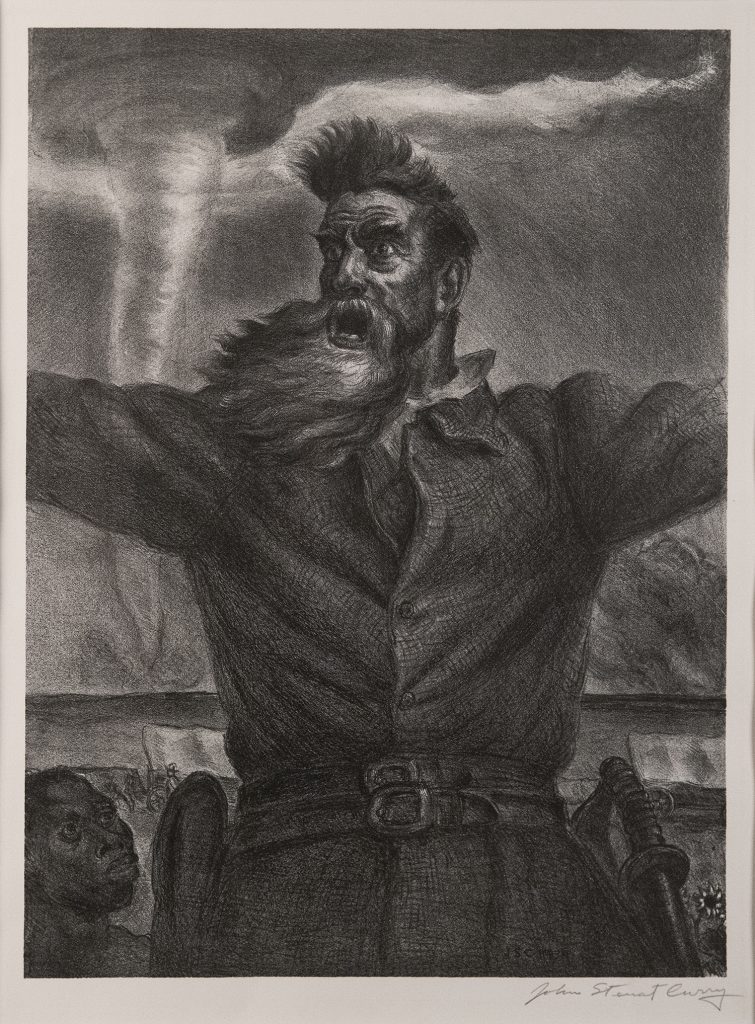

John Steuart Curry (1897-1946)

John Brown (1939)

Lithograph

18 1/2 × 13 3/8 (47 cm × 34 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Fearlessly shouting despite the tornado behind him, the radical emancipator John Brown stands as an immense and violent force of nature in John Steuart Curry’s depiction. In addition to demonstrating his determination, Brown’s wide eyes and angered countenance illustrate a notorious aspect of his historical identity–his insanity. Due to repeated, increasingly demoralizing business failures and an abusive, overbearingly religious upbringing, Brown seems to have become deeply unstable; he was plagued by violent voices in his head and delusions of grandeur. Eventually, Brown felt he was predestined to be a martyr, a Christ figure, for the abolitionist cause. He drafted a complete, rambling constitution for a slave-free, military-controlled state, and brutally dismembered several slave owners with an ax.

Despite Brown’s ferocity, a black man, probably a slave, looks at him calmly and admiringly, indicating the moral imperative to end slavery in the United States at any cost. An advocate for racial justice himself, Curry selected Brown as the subject for his 1939 mural for the Kansas State Capitol because he had been a leader in “Bleeding Kansas,” the pre-Civil War battle over slavery (1854–1861). The subject matter became so contentious that the state initially rejected Curry’s proposal. Outraged, Curry abandoned his contract with the state, prioritizing racial progress over material gain.

It took decades for Kansas to change course and approve the installation of Curry’s mural. In the meantime, he created lithographic versions of his call for radical action against racial injustice.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Atwater, Grayden Royce. “John Brown, Religion and Violence: Motivation in American History.” MA Thesis. Emporia State University, 2005

Cole, Sylvan. The Lithographs of John Steuart Curry: A Catalogue Raissonné. New York: Associated American Artists, 1976

Junker, Patricia, et al. John Steuart Curry: Inventing the Middle West. Manchester, Vermont: Hudson Hills, 1998

Kendall, M. Sue. Rethinking Regionalism: John Steuart Curry and the Kansas Mural Controversy. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1986