III. Places

III. Places

Over the centuries, artists have stirred interest in places familiar and unknown. Even if we have not visited them, famous places—Rome, Venice, Paris—have become immediately recognizable as a result of print reproductions. Similarly, prints express the lesser known: What do the lochs of Scotland look like? The French countryside? The ever-changing American city? Prints also deepen our connection to places with personal or sentimental attachments. And they evoke moods or emotions, in addition to providing visual information. Moreover, some prints portray places that exist only in the imagination.

The May Collection is especially rich in prints of places that attempt to express ideals of life, civilization, and beauty. The definition of what constitutes a “place” and how it should be portrayed is fluid, allowing artists across time, styles, and nationalities to offer distinctive interpretations of the genre.

Claude Lorrain (1604-1682)

French Landscape (1645)

Etching

8 7/16 × 10 13/16 (21.4 × 27.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Often celebrated as one of the greatest idealizing landscape painters of all time, Claude Lorrain also produced some forty-four landscape etchings. In order to appeal to the tastes of the Baroque era, Claude frequently included small scenes from the Bible or classical culture in his compositions. French Landscape exemplifies his fondness for the peaceful, pastoral world of shepherds and their flocks. In this etching, two peasants, a man and a woman, converse about the world around them, while their cows and goats amble out of a luxuriant forest toward a tranquil lake. The figures in dialogue evoke the utopia of Vergil’s Bucolics, poems in which shepherds reflect on philosophy, politics, art, and love. A quiet harmony between people and animals resonates through the landscape—perhaps expressing a longing for the unending beauty of nature. And yet, a bridge and roadway in the distance may indicate a connection to the more turbulent world of the city and court beyond.

Lorrain’s etching may echo the biblical Garden of Eden, wherein Adam and Eve live in perfect harmony with nature. Possibly, the woman’s gesture, pointing at the bridge that may lead to the real, corrupted world, could be a subtle nod to Eve’s decision to eat the forbidden fruit and convince Adam to do so also, expelling them from utopia.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Mannocci, Lino. The Etchings of Claude Lorrain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989

Pace, Claire. “The Golden Age… The First and Last Days of Mankind: Claude Lorrain and Classical Pastoral, with Special Emphasis on Themes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.” Artibus et Historiae 23 (2002): 127-156

Rumelin, Christian, et al. Claude Lorrain: The Enchanted Landscape. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2011 Wine, Humphrey. Claude: The Poetic Landscape. London: National Gallery Publications, 1994

Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778)

The Well, from Carceri d’Invenzione (1761)

Etching

16 1/8 × 21 1/2 (40.1 × 54.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who was also an architect, is renowned for his large-scale panoramic etchings and engravings of sites in Italy, especially of Rome and ancient Roman architecture.

Carceri d’Invenzione, a series of sixteen prints originally published in 1749, represent the immense, phantasmagorical interiors of “imaginary prisons.” To create these nightmarish views, Piranesi uses techniques of Baroque stage design: in particular, perspective (often with an eccentric vantage point), illusionism, and theatrical lighting. He includes staffage figures to establish the scale and the looming weight of the structure, while the stark chiaroscuro creates an ominous atmosphere. Piranesi’s reliance on both actual architectural principles and pure fantasy evokes a dreamlike suggestion of the great ruins of Roman architecture—the Carceri d’Invenzione are both technical and psychological marvels.

Sarah Treadway

Medicine, Health, and Society and Child Development

Class of 2021

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Marchesano, Louis. “Invenzioni Capric Di Carceri: The Prisons of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778).” Getty Research Journal 2 (2010): 151–160

Robison, Andrew. Piranesi, Early Architectural Fantasies: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Etchings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986

Yourcenar, Marguerite. The Dark Brain of Piranesi and Other Essays. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1984

Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768)

The Market at Dolo (1740s)

Etching

6 × 8 1/2 (15.3 × 21.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

A master at accentuating natural lighting, Giovanni Antonio Canal excelled at capturing the neoclassical grandeur of Venice. In addition to realistic cityscapes (called “vedute”), Canaletto developed a special subgenre called “capriccios,” compositions that blended buildings from actual Italian cities with imaginary architecture and settings. His prowess for depicting fantastical landscapes likely stems from his early training as a designer for theater sets.

The Market at Dolo, a fanciful depiction of a Venetian village on the mainland, is one of his later capriccios. It exemplifies his theatrical yet realistic style, with tradespeople working in the foreground of the Venetian lagoon, against a backdrop of stately buildings and a majestic mountain. Even in the absence of coloring, Canaletto demonstrates his prowess with handling light. He illuminates the workers and the building nearest the viewer, while obscuring a distant façade and the lower portion of the mountain, precisely fixing the sun’s position, while its rays are felt in every corner of the image.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Baetjer, Katharine, et al. Canaletto. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013

Bromberg, Ruth. Canaletto’s Etchings: Catalogue Raisonné. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1993Constable, William George. “A Canaletto Capriccio.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 47 (1949): 81-84

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Driving Rain at Shōno (1833), Station Forty-Five from Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833-1834)

Color woodblock print

10 x 14 15/16 (25.4 x 38 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Originally developed for the ruling shogun in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to bring offerings to the emperor’s palace in Kyoto, the Tōkaidō became the most heavily traveled highway in Japan. Tourist travel boomed in the nineteenth century as the romantic notion of sightseeing captured the popular imagination and families set out on pilgrimages to see the beauty of the Japanese landscape. The government set up fifty-three stations along the scenic Tōkaidō as stopping points for travelers to rest, marking the road with clusters of inns, restaurants, shrines, and shops.

Hiroshige’s Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō combines the beauty of the natural landscape, the romantic myth of travel and exploration, and realistic images of everyday life and work into a collection of souvenir prints. Driving Rain at Shōno, which could be collected at the forty-fifth stop along the route, captures a moment of frantic panic. Confusion abounds as figures wearing bamboo raincoats scramble to find shelter from the pouring rain. In this tour de force of the woodcut medium, Hiroshige creates an atmospheric setting by layering washes of diagonal rain against receding thickets of bamboo, illustrating each successive layer with less detail to construct a sense of mist and depth.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Calza, Gian Carlo. Hiroshige: The Master of Nature. London: Rizzoli International Publications, 2009

Naitō, Masato. “Andō Hiroshige.” Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford Art Online

Sasaki, Moritoshi. Tōkaidō gojūsantsugi (Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō). Tokyo: Nigensha, 2010

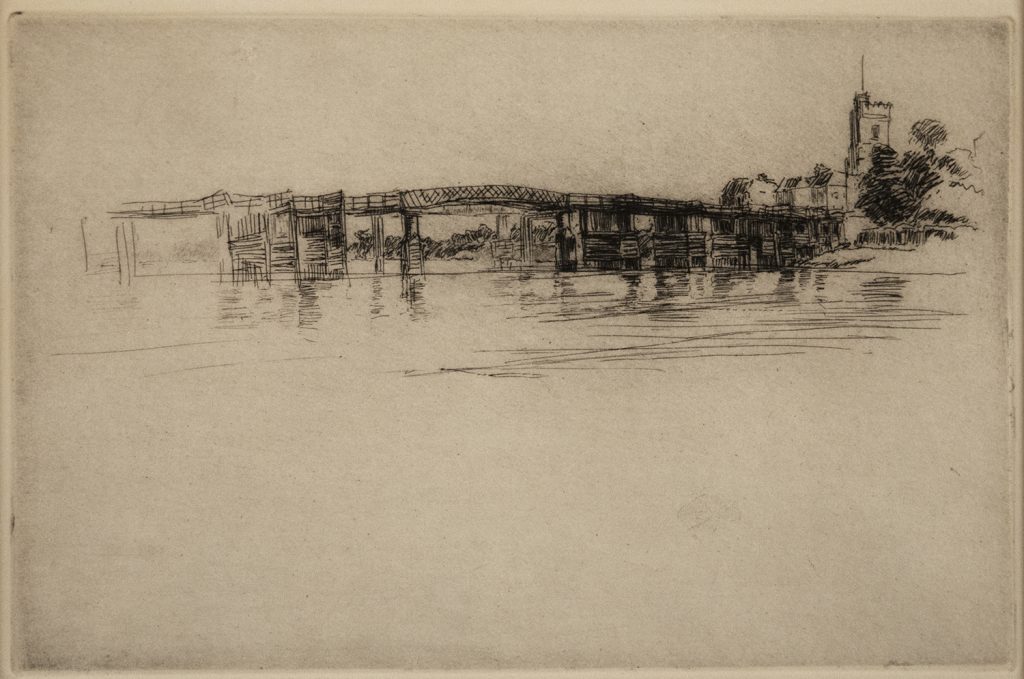

James A. McNeill Whistler (1834-1903)

Bridge at the Little Putney (1879)

Etching and drypoint

6 15/16 × 9 9/16 (17.6 × 24.3 cm)

Collection of Jack May

In contrast to the sharply defined warehouses in Black Lion Wharf (on display in Painters and the Print), Whistler’s Bridge at the Little Putney is a nebulous, impressionistic take on London’s Putney Bridge. Although the Putney Bridge may no longer be functional in the etching (it was demolished within months of this composition), Whistler celebrates its inherent beauty and delicacy, transforming it into a serene, natural landscape on the edge of London. With this image of the elegant fragility of an obsolete bridge, Whistler may be demonstrating the ideal of art for the sake of art (l’art pour l’art), although it may be a sentimental look at the passage of time and the decay of all things human-made. Either way, Putney Bridge challenges our expectation that functionality and utility are defining characteristics of an urban landscape.

Peter Stidman

Law, History, & Society

Class of 2023

Immersion Project

Recommended Sources

Lochnan, Katharine. The Etchings of James McNeill Whistler. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984

MacDonald, Margaret F., and Patricia de Montfort. An American in London: Whistler and the Thames. London: Phillip Wilson Publishers, 2013

Sutherland, Daniel E. Whistler: A Life for Art’s Sake. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014

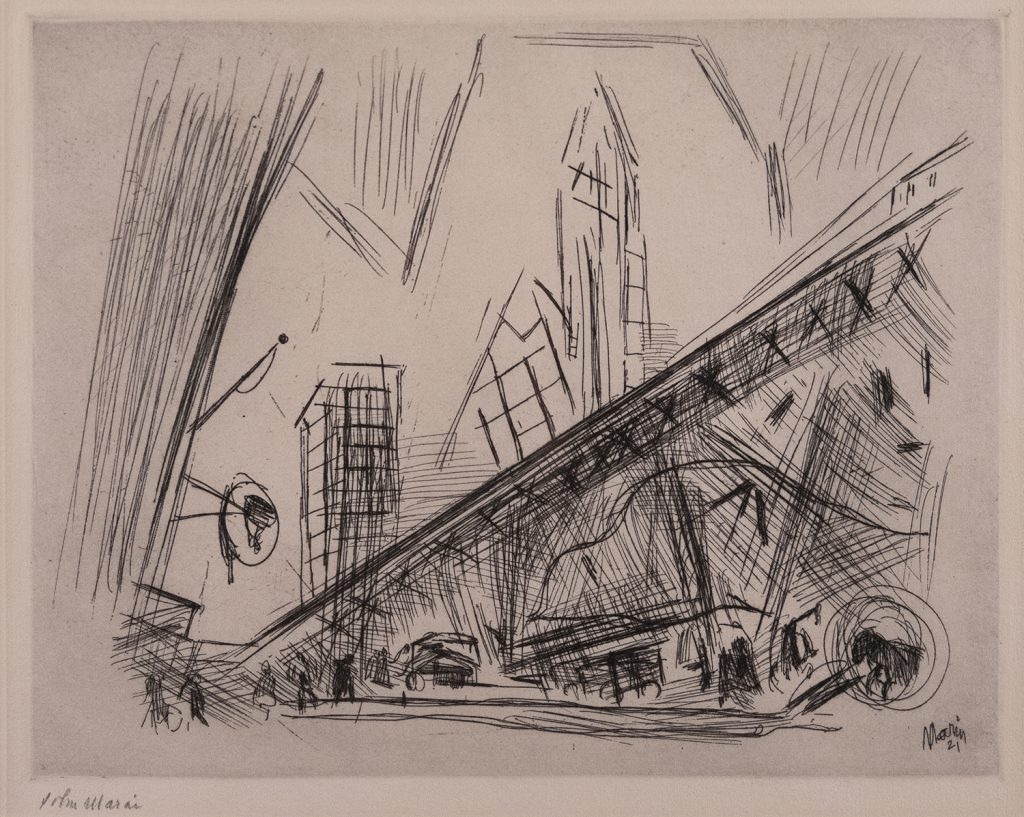

John Marin (1870-1953)

Downtown, The El (1921)

Etching

6 7/8 × 8 7/8 (17.5 × 22.5 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Facing financial hardships, The New Republic magazine offered a special promotion on December 10, 1924: for twelve dollars, readers could receive both a two-year subscription and a portfolio of six fine art etchings, including works by the major American artists Peggy Bacon, Edward Hopper, John Marin, and John Sloan. Jack May’s father, Dan, knew a deal when he saw it and, foreshadowing his son’s collecting passion, subscribed.

One of the six prints is Marin’s Downtown, the El, a dynamic image of New York City’s elevated train line. The bold diagonals and fractured planar forms convey the hustle and bustle of a city in motion. In the background, the soaring Woolworth Building, the tallest structure in the world at the time, accentuates the skyline’s explosive upward growth. Not only does Marin represent the complex metropolitan ecosystem of pedestrians, transportation, and skyscrapers, but his quick sketch-like style also captures the excitement of the distinctively American cityscape emerging in the modern world.

Although most subscribers received a copy of Downton, the El, Marin’s art promoter Alfred Stieglitz initially suggested that The New Republic use a different print titled Brooklyn Bridge, No. 6 (1913). Several inches larger than the rest of the works in the set, only a few prints were made from this initial plate before the magazine switched to the smaller Downton, the El. Fewer than fifty initial subscribers received signed copies of the larger print.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Fine, Ruth E. John Marin. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1990

Melby, Julie. “The New Republic’s Portfolio of 1924.” Print Quarterly 22 (2005): 397-411

Zigrosser, Carl. The Complete Etchings of John Marin: Catalogue Raissoné. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1969

Edward Hopper (1882-1967)

Night Shadows (1921)

Etching

13 3/16 × 14 7/16 (33.5 × 36.6 cm)

Collection of Jack May

In his early career, the American painter Edward Hopper produced circa 70 etchings. As exemplified by Night Shadows, his prints often transform realistic New York City scenes into edgy dramas that evoke the cinematic style of film noir. By contrasting heavily etched intaglio line against the stark white paper, he vividly portrays the movement of a lone figure, traversing a gloomy cityscape. The unusual composition heightens its suggestions of alienation by imposing a physical and emotional distance between us, the voyeuristic viewers, looking from an undefined perch above, and the solitary man walking below. Intentional sensory imagery makes hollow footsteps sound eerily on the sidewalk as we spy on him. With its artificial light and shadow, Night Shadows captures the psychological unease of the rapidly modernizing city.

Night Shadows was also in the portfolio of six prints from The New Republic magazine promotion.

Sophia Moak

Mechanical Engineering

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: A Catalogue Raisonné. 4 vols. New York: Norton, 1995

Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography. New York: Rizzoli, 2007

Hale Woodruff (1900-1980)

Relics (1935)

Linocut

9 x 11 1/8 (22.9 x 28.3 cm)

Collection of Vanderbilt University

Nashville-raised Hale Woodruff is among America’s most prominent twentieth-century Black artists. He trained in Indianapolis, Chicago, Boston, and Paris, and studied mural painting under Diego Rivera. Active during the Great Depression, Woodruff had a successful teaching career as professor of art at Atlanta University and New York University. Bold, curvilinear expressiveness, as evident in this linocut, remained a salient element of his style throughout his career.

Created during his Atlanta period (1931-1946), Relics presents a triste image of a dilapidated barn and a gaunt donkey, a synecdoche for the plight of the South during the Great Depression. Woodruff focused on the socio-economic impact on Black southerners, saying that he was “expressing the South as a field, as a territory, its peculiar run-down landscape, its social and economic problems of the Negro people.” This print may have Christian undertones, evoking a manger scene, thus alluding to the humble origins of a messiah and the promise of a brighter future.

This is the first acquisition made with the Jack May History of Prints Fund, established by his family at Vanderbilt University in 2019, on the occasion of May’s 90th birthday.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

“Woodruff, Hale.” Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford Art Online

Sumrell, Morgan. “Hale Woodruff: the Harlem Renaissance in Atlanta.” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 37 (2013): 115-53

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975)

Homestead (1938)

Lithograph

9 × 13 1/8 (22.9 × 33.3 cm)

Collection of Jack May

As Modernism swept across Europe in the early twentieth century, many American artists steadfastly adhered to a realist aesthetic, creating a style that historians have labelled the “American Scene.” The American Scene artists who explored rural America (sometimes called Regionalists) often framed hardworking mid-Westerners as the backbone of the nation. Thomas Hart Benton, a leader of the American Scene, contended that subject matter rather than style defined a work of art. Benton casts the artist as a visual social historian.

Homestead, a lithographic version of a 1934 mural, depicts a modest farm during the Depression and emphasizes the discontinuity between the romantic ideal of the American farm and the grim realities of the era. Despite his rejection of abstract art, Benton was influenced by Synchronism, an early twentieth-century movement that associated visual art and music. This is evident in the sinuous forms and rhythmic lines of this composition.

Benton’s final project was The Sources of Country Music, a mural for Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame left unfinished at the time of his death.

Chloe Davis

History of Art and Anthropology

Class of 2020

HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Fath, Creekmore West. The Lithographs of Thomas Hart Benton. 2nd ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990

Lyonel Feininger (1872-1956)

Off the Coast (Vor der Küste) (1951)

Lithograph

9 1/16 × 15 1/2 (23 × 39.4 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Although Lyonel Feininger grew up in New York City, his artistic identity was largely formed while working in Germany. At the height of a successful international career, he was appointed the first professor of graphic art at the Bauhaus, the most influential school for modern design.

Off the Coast (Vor der Küste), inked near the end of the artist’s life, synthesizes Feininger’s various modernist influences. The print combines Cubism’s angular forms with the emotionality of German Expressionism, while the medium itself draws upon the Bauhaus’s promotion of mass production. Starting in the 1920s, the Nazi Party condemned these movements for their supposed Jewish, Communist, or otherwise “un-German” elements. Several of Feininger’s works were featured in the infamous 1937 exhibition of Degenerate Art (“entartete Kunst”) as examples of art that subverted Nazi ideals of beauty. Later that year, Feininger fled Nazi Germany for America.

Using harsh lines and discordant shading, the artist undermines the clichéd idyll of a sailboat on water. Though the print captures the beauty of the Baltic seascape, it also recognizes the stormy conditions of German political and social life.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Luckhardt, Ulrich. Lyonel Feininger. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1989

Haskell, Barbara, and Sasha Nicholas. Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2011

Prasse, Leona E. Lyonel Feininger: A Definitive Catalogue of His Graphic Work: Etchings, Lithographs, Woodcuts (English and German Edition). Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1972

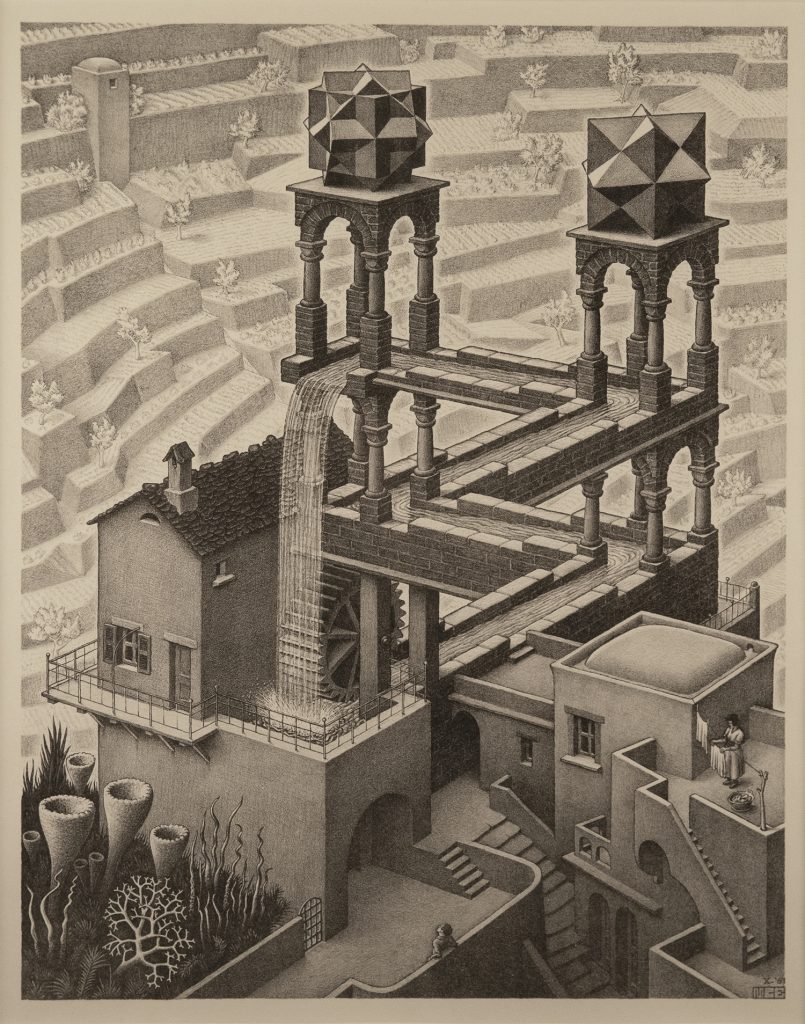

M. C. Escher (1898-1972)

Waterfall (1961)

Lithograph

14 15/16 × 11 13/16 (38 × 30 cm)

Collection of Jack May

Rather than depicting an actual location, M. C. Escher presents an imaginary space composed of thought and theory. At first glance, the depiction of water cascading from a raised platform seems fairly straightforward. Further scrutiny, however, reveals the perplexing detail that the water is flowing upwards from the base of the falls in defiance of gravity. Employing “impossible tribars,” a type of “impossible object” described by mathematician Roger Penrose and psychiatrist Lionel Penrose, Escher aligns his canals at paradoxical angles. The viewer is left with the futile struggle to reconcile the overlaid points of view, while a sense of the unnatural is further accentuated by the large polyhedrons placed atop the impossible structure. Moreover, the artist playfully alludes to elements of the real world: the miller needs to add the occasional bucket of water to offset evaporation and quaint old-fashion structures surround the mill, clashing with the initial impressions of unfamiliarity.

In addition to his artistic appeal, Escher is a fan favorite of mathematicians and scientists. While posters of his works are a staple in math classrooms, his designs have been used as the framework for complex or seemingly paradoxical scientific phenomena including transition metal atomic behavior, topology optimization, and group rationality.

Cainie Brown

Anthropology and History of Art

Class of 2022

Immersion Project & HART 2775: History of Prints

Recommended Sources

Locher, J. L., ed. Escher: The Complete Graphic Work. London: Thames and Hudson, 1992

Penrose, Lyonel S., and Roger Penrose. “Impossible Objects: A Special Type of Visual Illusion.” British Journal of Psychology 49 (1958): 31-33

Schattschneider, Doris. M. C. Escher: Visions of Symmetry. New York: W. H. Freeman, 1990